Management of type 2 diabetes in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance

BMJ 2016; 353 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1575 (Published 06 April 2016) Cite this as: BMJ 2016;353:i1575

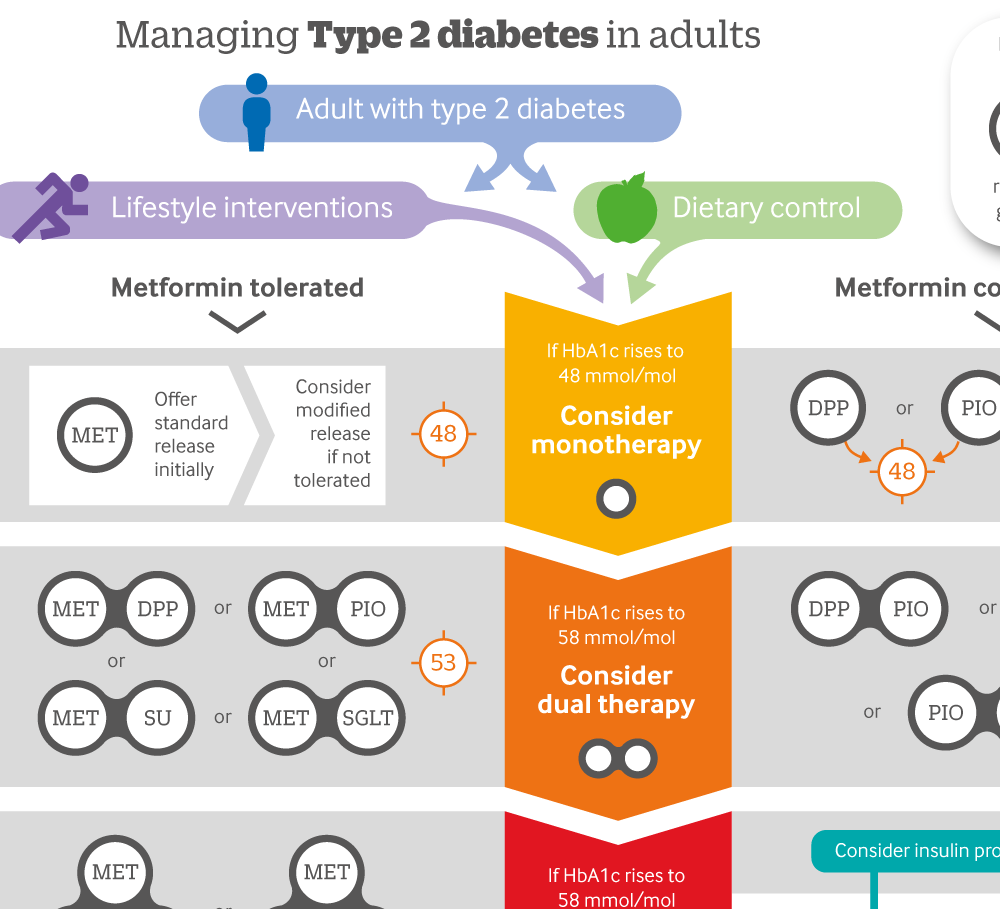

Infographic: Managing type 2 diabetes in adults

Click here to see a visual summary of the NICE guidelines on the use of single, dual or triple therapy with blood glucose lowering drugs, and when to consider an insulin programme.

Chinese translation

该文章的中文翻译

- Hugh McGuire, technical advisor1,

- Damien Longson, guideline chair2,

- Amanda Adler, consultant physician3,

- Andrew Farmer, professor of general practice4,

- Ian Lewin, consultant diabetologist5

- on behalf of the Guideline Development Group

- 1National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London, UK

- 2Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust, Manchester M21 9UN, UK

- 3Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

- 4University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 5Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust, Barnstaple EX31 4JB, UK

- Correspondence to: H McGuire Hugh.McGuire{at}nice.org.uk

What you need to know

Glycaemic control is only one aspect of care of type 2 diabetes

Inform adults with type 2 diabetes at their annual review that setting an HbA1c target is their choice

Metformin remains the first line drug, unless it is contraindicated or not tolerated

Do not routinely offer self monitoring of blood glucose to all

New evidence and developments regarding the management of blood glucose levels, antiplatelet therapy, and erectile dysfunction prompted this update of the 2009 guidance. There were safety concerns surrounding some blood glucose lowering medicines, new evidence on new dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, new indications and combinations for licensed drugs, and the potential impact of drugs coming off patent on health and economic issues. New evidence and safety issues relating to the off label use of antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease were also considered.

Type 2 diabetes affects 6% of the UK population1 and is commonly associated with obesity, physical inactivity, raised blood pressure, and disturbed blood lipid levels. It causes long term microvascular and macrovascular complications, plus reduced quality of life and life expectancy. The management of diabetes is complex and needs to address the prevention of cardiovascular disease and microvascular disease and the detection and management of early vascular complications.

This article summarises the most recent recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),2 recently updated due to the availability of new evidence and developments. The article also summarises a selection of recommendations which still stand.

What’s new in this guidance

The suggested target level for HbA1c has been relaxed to ≤48 mmol/mol (≤53 mmol/mol if more than one drug is prescribed)

Separate medication pathway for those who are unable to take metformin

Do not give aspirin or clopidogrel for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease

Recommendations

NICE recommendations are based on systematic reviews of best available evidence and explicit consideration of cost effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available, NICE bases recommendations on the Guideline Development Group’s experience of what constitutes good practice. When exercising their judgement, healthcare professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences, and values of their patients or service users. The application of the recommendations in this guideline is not mandatory

Patient education

Offer a structured education programme to adults with type 2 diabetes and their family members or carers at or around the time of diagnosis, with annual reinforcement and review. [2009, based on low quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the Guideline Development Group (GDG)]

The full guidance contains information for those responsible for developing and monitoring such programmes.

Integrate dietary advice with a personalised plan to manage diabetes, including other aspects of lifestyle modification such as increasing physical activity and losing weight when appropriate. [2009, based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Managing blood glucose

Involve adults with type 2 diabetes in decisions about their individual HbA1c target.

Aim to avoid adverse effects (including hypoglycaemia) or efforts to achieve their target which impair their quality of life. [2015, based on high to very low quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Involve adults with type 2 diabetes in decisions about their care, individualising this to take account of each person’s preferences, comorbidities, risks from polypharmacy or tight glucose control, and life expectancy. [2015, based on low quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Support adults to aim for a HbA1c target of 48 mmol/mol, rising to 53 mmol/mol as treatment intensifies. [2015, based on low quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Do not routinely offer self monitoring of blood glucose levels for adults with type 2 diabetes unless:

The person is taking insulin

The person is taking oral medication that may increase the risk of hypoglycaemia while driving or operating machinery

There is evidence of hypoglycaemia

The person is pregnant, or is planning to become pregnant. (For more information, see the NICE guideline on diabetes in pregnancy)

It is part of a structured education programme to help patients understand their diabetes or identify asymptomatic hypoglycaemic events.

[2015, based on high to very low quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Drug treatment

Offer metformin (standard release) as the initial drug treatment. [2015, based on high quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

If metformin (standard release) is contraindicated or not tolerated, consider initial drug treatment with metformin (extended release) or a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, pioglitazone, or a sulfonylurea. [2015, based on extrapolated evidence in population where metformin is indicated and tolerated and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

See linked infographic for offering treatment beyond these drugs in response to changes in HbA1c.

The GDG concluded that the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidance and patient suitability should be considered for pioglitazone. Pioglitazone is associated with an increased risk of heart failure, bladder cancer, and bone fracture. Known risk factors for these conditions, including increased age, should be carefully evaluated before treatment. The MRHA advises that prescribers should review individuals after 3-6 months of treatment, and continue treatment only if benefit is seen.

The GDG noted there was limited information on the long term safety of DPP-4 inhibitors but considered the evidence was strong enough to recommend these as treatment options if both other drugs were contraindicated or not tolerated, but again the MHRA guidance should be considered.

When starting insulin therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes, use a structured programme employing active insulin dose titration that encompasses:

Injection technique

Continuing telephone support

Self monitoring

Dose titration to target levels

Dietary understanding

Notifying the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA)

Management of hypoglycaemia

Management of acute changes in plasma glucose control

Support from an appropriately trained and experienced healthcare professional.

[2015, based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Management of selected related risks and symptoms

The role of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction in men with type 2 diabetes has been changed and it is now a weaker recommendation (see below) because of concerns about the quality of the evidence and the lack of comparative data versus testosterone.

Consider a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor to treat problematic erectile dysfunction in men with type 2 diabetes, initially choosing the drug with the lowest acquisition cost and taking into account any contraindications. [new 2015, based on low quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

After reviewing the role of aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes, the GDG decided that neither aspirin nor clopidogrel should be offered for adults with type 2 diabetes without cardiovascular disease.

Do not offer antiplatelet therapy (aspirin or clopidogrel) for adults with type 2 diabetes without cardiovascular disease. [New 2015, based on low quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

There are no changes in recommendations to manage blood pressure in adults with type 2 diabetes.

Add medications if lifestyle change does not reduce blood pressure to below 140/80 mm Hg (below 130/80 mm Hg if there is kidney, eye, or cerebrovascular damage). [2009, based on high quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Monitor blood pressure every one to two months, and intensify therapy if the person is already taking antihypertensive drug treatment, until the blood pressure is consistently at or below 140/80 mm Hg (at or below 130/80 mm Hg if there is kidney, eye, or cerebrovascular damage). [2009, based on high quality evidence and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

How patients helped create this guidance

The GDG included lay members who helped formulate the recommendations summarised here.

Guidelines into practice

Has everyone with a diagnosis of diabetes in the last year been offered a structured education programme?

Have you offered lifestyle advice, including diet and physical activity, to the person with type 2 diabetes at this visit?

Have you considered whether standard HbA1c targets should apply for those with comorbidities, frailty, or advanced age?

Further information on the guidance

Methods

This guidance was developed by the Internal Clinical Guidelines team using current NICE guideline methodology (www.nice.org.uk/guidelinesmanual). The guidance review process involved literature searches to identify relevant evidence, and critically appraising the quality of the evidence identified. Health economic modelling was used to inform disease on the pharmacological management of glycaemic control. A multidisciplinary team of service users, carers, and healthcare professionals (including diabetologists, general practitioners, pharmacists, nurse specialists, and patient and carer representatives) was established—the Guideline Development Group (GDG)—to review the evidence and develop the subsequent recommendations. The guidance then went through an external consultation with stakeholders. The GDG considered the stakeholders’ comments, reanalysed the data where necessary, and modified the guidance as appropriate.

NICE has produced three different versions of the guidance: a full version; a summary version known as the “NICE guidance”; and a version for people using NHS services, their families and carers, and the public (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG28/ifp/chapter/about-this-information). All these versions are available from the NICE website (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28). Further updates of the guidance will be produced as part of NICE’s guideline development programme. Tools to help implement the guidance are available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/resources.

When will this guideline be updated?

NICE is currently considering setting up a standing update committee for diabetes, which would enable more rapid update of discrete areas of the diabetes guidelines, as and when new and relevant evidence is published.

Future research

Based on its review of evidence, the GDG has recommended the following research to improve care:

How does stopping and switching drug treatments affect levels of blood glucose levels, and what criteria should inform the decision?

For people who cannot take metformin, what drug combinations are most effective when initial non-metformin monotherapy fails to control blood glucose levels?

When a third intensification of treatment is indicated, which therapies should be used to control blood glucose?

What are the long term complications and effects on blood glucose control with drugs such as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and meglitinides?

In adults for whom self monitoring of blood glucose is appropriate, what is the optimal frequency for self monitoring?

Footnotes

The members of the Guideline Development Group were: Damien Longson (guideline chair), consultant liaison psychiatrist, Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust; Amanda Adler, consultant physician, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Anne Bentley, medicines optimisation lead pharmacist, NHS East Lancashire Primary Care Trust; Christine Bundy (co-opted expert member), senior lecturer in behavioural medicine, Institute for Inflammation and Repair, University of Manchester; Bernard Clarke (co-opted expert member), honorary clinical professor of cardiology, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, University of Manchester; Maria Cowell, community diabetes specialist nurse, Cambridge; Indranil Dasgupta (co-opted expert member), consultant nephrologist, Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham; David Ronald Edwards, principal in general practice, Whitehouse Surgery, Oxfordshire; Andrew Farmer, professor of general practice, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford; Natasha Jacques, principal pharmacist in diabetes, Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham; Yvonne Johns, patient/carer member; Ian Lewin, consultant diabetologist, North Devon District Hospital, Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust; Natasha Marsland, patient/carer member, Diabetes UK; Prunella Neale, practice nurse, Herschel Medical Centre, Berkshire; Jonathan Roddick, principal general practitioner, Woodseats Medical Centre, Sheffield; Mohammed Roshan (August 2012 to October 2013), principal in general practice, Leicester City and County; Sailesh Sankar, consultant diabetologist, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust.

Contributors: HM wrote the first draft of this manuscript; all authors reviewed and revised it and approved the final version for publication. HM is guarantor.

Funding: NICE was funded by the Department of Health to develop this clinical guideline.

Competing interests: We declare no competing interests, based on NICE’s policy on conflicts of interests (available at www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/Who-we-are/Policies-and-procedures/Code-of-practice-for-declaring-and-managing-conflicts-of-interest.pdf). Full details of the Guideline Development Group’s interests are available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/chapter/4-The-Guideline-Development-Group-Internal-Clinical-Guidelines-team-and-NICE-project-team-and-declarations-of-interests

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.