Abstract

Background

Although the increasing use of drugs in elderly persons has raised many concerns in recent years, the process leading to polypharmacy (PP) and excessive polypharmacy (EPP) remains largely unknown.

Objective

To describe the number and type of drugs used and to evaluate the role of different factors associated with PP (i.e. 6–9 drugs) and EPP (i.e. ≥10 drugs), with special reference to the number and type of medical diagnoses and symptoms, in a population of home-dwelling elderly persons aged ≥75 years.

Methods

The study was a cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort in 1998. The population consisted of home-dwelling elderly persons aged ≥75 years in the city of Kuopio, Finland. The data for the analysis were obtained from the Kuopio 75+ Study, which drew a random sample of 700 elderly residents aged ≥75 years living in the city of Kuopio from the population register. Of these, 601 attended a structured clinical examination and an interview carried out by a geriatrician and a trained nurse in 1998. For this analysis, all home-dwelling elderly participants (n = 523) were included. Study data were expressed as proportions and means with standard deviations. The factors associated with PP and EPP were examined by multinomial logistic regression.

Results

The most commonly used drugs were cardiovascular drugs (97% in EPP, 94% in PP and 59% in non-PP group) and analgesics (89%, 76% and 54%), respectively. Use of psychotropics was markedly higher in the EPP group (77%) than in the PP (42%) and non-PP groups (20%). The mean number of drugs per diagnosis was 3.6 in the EPP group, 2.6 in the PP group and 1.6 in the non-PP group. Factors associated only with EPP were moderate self-reported health (odds ratio [OR] 2.05; 95% CI 1.08, 3.89), female gender (OR 2.43; 95% CI 1.27, 4.65) and age ≥85 years (OR 2.84; 95% CI 1.41, 5.72). Factors that were associated with both PP and EPP included poor self-reported health (PP: OR 2.15; 95% CI 1.01, 4.59 and EPP: OR 6.02; 95% CI 2.55, 14.20), diabetes mellitus (PP: OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.26, 4.15 and EPP: OR 2.07; 95% CI 1.03, 4.18), depression (PP: OR 2.13; 95% CI 1.16, 3.90 and EPP: OR 2.93; 95% CI 1.51, 5.66), pain (PP: OR 2.69; 95% CI 1.68, 4.30 and EPP: OR 2.74; 95% CI 1.56, 4.82), heart disease (PP: OR 2.51; 95% CI 1.54, 4.08 and EPP: OR 4.63; 95% CI 2.45, 8.74) and obstructive pulmonary disease (including asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) [PP: OR 2.79; 95% CI 1.24, 6.25 and EPP: OR 6.82; 95% CI 2.87, 16.20].

Conclusions

The study indicates that the factors associated with PP and EPP are not uniform. Age ≥85 years, female gender and moderate self-reported health were factors associated only with EPP, while poor self-reported health and several specific disease states were associated with both PP and EPP. The high number of drugs per diagnosis observed in this study calls for a thorough assessment of the need for and outcomes associated with use of these drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The use of drugs in elderly persons has received much attention in recent years, with several studies showing increasing prevalence of polypharmacy in frail elderly populations.[1–3] In Finnish elderly persons aged ≥65 years, the prevalence of polypharmacy (i.e. five or more drugs in use) increased from 6% to 25% during a 10-year period from the late 1980s to the late 1990s.[4,5] During the 2000s, the prevalence has further increased, probably because of the availability of new treatment options for elderly persons; however, estimates are available only for the ≥75 year age group, of whom 67% were reported to use six or more drugs in one study.[6]

Although a consensus on the definition of polypharmacy is still lacking, in many studies polypharmacy refers to concomitant use of five or more drugs. Using this definition, worldwide prevalence estimates of polypharmacy in the 1990s ranged from 9% to 39% in persons aged ≥65 years,[7–10] with the highest prevalence having been reported in the US[11,12] and Nordic countries.[5,13] During the 2000s, the prevalence has risen significantly in this age group, with all recent studies having reported that over half of elderly persons receive polypharmacy.[14,15] In Nordic countries, one of the factors contributing to the increase in polypharmacy is the reimbursement system, which allows universal access to prescription drugs by refunding and subsidizing the expenses of drugs for all citizens equally.[16]

Only a few studies have reported the prevalence of excessive polypharmacy, defined as the use of nine or more drugs concomitantly. In these few studies, the prevalence ranged from 13% to 39% in home-dwelling elderly persons.[6,13,17–19] This variation can partly be explained by different definitions of drug use: some studies take into account only long-term use of prescription drugs, while others include over-the-counter drugs, vitamins and mineral supplements.

Previous studies have shown that factors associated with polypharmacy include age, female gender, poor self-reported health, low education, institutional living and a high number of visits to healthcare professionals.[5,6,20–23] Moreover, multimorbidity and especially diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases have been found to be associated with polypharmacy.[24] No previous studies have studied the associations of these factors with excessive polypharmacy.

The more drugs an elderly person uses, the greater the likelihood of lower adherence to the medication regimen and poorer health outcomes.[25,26] Polypharmacy has also been reported to increase the risk of hospitalizations[27] and falls.[28] In addition, polypharmacy is associated with increased occurrence of adverse drug effects, drug-drug interactions and inappropriate medication.[29–31]

Information about the process leading to polypharmacy and, especially, to excessive polypharmacy, is largely lacking. The aims of this study were to describe the number and type of drugs used and to evaluate the role of different factors associated with polypharmacy (defined in this study as 6 to 9 drugs) and excessive polypharmacy (defined in this study as 10 or more drugs), with special reference to the number and type of medical diagnoses and symptoms in a population of home-dwelling elderly persons aged ≥75 years.

Methods

Participants in the Kuopio 75+ Study

The data used in this study were obtained from the population-based Kuopio 75+ Study,[6] which focuses on the clinical epidemiology of diseases, drug use and functional capacity in elderly persons. Eligibility criteria included age ≥75 years and living in the city of Kuopio, Finland (n = 4518). A random sample of 700 persons was drawn from this population on 1 January, 1998. Fifteen of these persons died before being surveyed, and 84 refused to participate or could not be contacted. Altogether, 601 persons took part in the baseline study in 1998, yielding a participation rate of 86%. For this study, only participants living at home at baseline (n = 523, 87% of participants) were included. A follow-up of survivors (n = 339) was conducted in 2003.

Data Collection

A trained nurse interviewed the participants and recorded the drugs that the elderly persons were taking regularly or as needed, based on the drug containers and prescriptions that the participants were asked to bring with them. Vitamins and herbal products were also documented. In addition, a geriatrician examined the participants and diagnosed their current diseases. The participant’s medical records were reviewed thoroughly to obtain a comprehensive history. The reliability of current and former diagnoses was improved by checking primary- and secondary-care records (from Kuopio University Hospital, municipal hospitals, local hospitals and home nursing services) that provided long-term information about the participant’s health status. During the interview and examination, information on the participants’ sociodemographic background, living conditions, social contacts, health behaviour and health status was also recorded.

Interviews and examinations were conducted mainly in the outpatient clinic of the municipal hospital. Participants who could not attend the clinic were examined at home. If participants were unable to answer the questions, a close relative or caregiver gave the required information. The follow-up in 2003 was conducted using the same set of procedures as for the baseline examination, with the exception that there was no clinical examination by a physician.

Ethical Issues

Written informed consent was obtained for participation in the Kuopio 75+ Study from the participants themselves or their relatives. Ethical approval was granted by the ethical committee of the Hospital District of Northern Savo and the University Hospital of Kuopio.

Definitions and Measures

Excessive polypharmacy was defined as the concomitant use of ten or more drugs taken regularly or as-needed; polypharmacy was defined as the use of six to nine drugs. The non-polypharmacy group included persons using five or less drugs concomitantly.

In this article, drug use refers to regular and as-needed consumption of drugs and vitamins. Herbal products were excluded because information on their use could not be consistently collected. Drugs taken daily or at regular intervals were defined as being in regular use. All such drugs were classified according to therapeutic class.

The current clinical diagnoses of diseases were based on patient records and the clinical examination by a geriatrician. A structured data collection form was used in the examination.

As mentioned in the Data Collection section, information about the participant’s former medical conditions was available from primary- and secondary-care medical records. The diagnoses of dementia and depression were evaluated according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition) criteria.[32] Pain was coded as present when the participant reported regular pain disturbing daily life or rest pain. In the analyses, heart disease (including coronary heart disease, cardiac insufficiency, atrial fibrillation, valvular insufficiency or stenosis) and obstructive pulmonary disease (including asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) were recorded as present or absent. Self-reported health was measured on a 5-point scale. For this study, health status was classified into the following three classes: good (= very good/good), moderate or poor (= fairly poor/poor).

When counting the number of diagnoses for each participant, claudication, diabetes, dementia, depression, history of stroke, hypertension, pain and obstructive pulmonary disease were taken into account. Coronary heart disease, cardiac insufficiency, atrial fibrillation, valvular insufficiency and stenosis were counted as heart diagnoses. These disease states were chosen based on previous study results and reliable information available from the examination and patient records. The number of drugs per diagnosis was counted individually by dividing the number of drugs in use by the number of diagnosed diseases.

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from this study are expressed as proportions and means with standard deviations (SD). For categorical variables, the statistical significance of the differences between polypharmacy groups was evaluated using a chi-squared (χ2) test. The statistical significance of differences in the means of the continuous age variable was evaluated using a Kruskal-Wallis test because the assumption of normality was not met. Normality was analysed by a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and equality of variances by a Levene test.

Multinomial logistic regression was used to determine the factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy. Potential variables were selected on the basis of previous studies reporting risk factors for increasing use of drugs in elderly persons. The original multivariate model included gender, age group, living alone, self-reported health, claudication, diabetes, dementia, depression, history of stroke, hypertension, pain, presence of heart disease and presence of obstructive pulmonary disease. Variables were discarded from the model if they were not significantly associated with outcomes and their removal did not affect the reported associations (change in odds ratios [OR] <10%). The final model was fitted for persons (n = 472) for whom data on all measured covariates, including gender, age group, self-reported health, diabetes, depression, hypertension, pain, presence of heart disease and presence of obstructive pulmonary disease, were available. As a result, 51 persons were excluded because of missing data on at least one study variable. The differences between persons included and not included in the regression analysis were tested using the χ2 test. The results revealed that those excluded more commonly experienced hypertension (p = 0.037) and less commonly experienced depression (p = 0.048) than those included in the regression analysis.

In this study, p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Description of Study Population

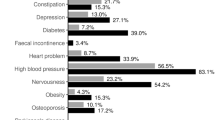

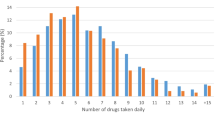

The majority of home-dwelling elderly participants were women (n = 380, 73%) [table I]. Their mean age was 81 years (range 75–96). Almost all participants were taking some drugs: only 11 (2%) were not taking any drugs at all. The mean number of drugs in use per participant was 12.1 in the excessive polypharmacy group, 7.4 in the polypharmacy group and 3.1 in the non-polypharmacy group.

Persons in the excessive polypharmacy group (23% of the total population) were slightly older than those in the polypharmacy (34% of the total population) and non-polypharmacy (43% of the total population) groups (table I). A greater proportion of persons with excessive polypharmacy reported their health as poor (32%) compared with persons in the polypharmacy (19%) and non-polypharmacy (8%) groups. Overall, persons with excessive polypharmacy were more likely to have various diseases than persons in the other groups. A significant difference was also observed in the average number of diagnoses between polypharmacy groups (table I).

Number and Type of Drugs

The mean number of drugs in use per diagnosed disease in the excessive polypharmacy group was 3.6. Persons in the polypharmacy group were treated with a mean 2.6 drugs per disease, compared with a mean 1.6 drugs per disease in the non-polypharmacy group.

The most commonly used drugs were cardiovascular drugs (table II). The majority of persons in the excessive polypharmacy (97%) and polypharmacy groups (94%), and over half of persons in the non-polypharmacy group (59%), used these drugs. The mean number of cardiovascular drugs used in these groups was 3.8, 2.9, and 1.0, respectively (figure 1). Nitrates, β-adrenoceptor antagonists and diuretics were the most commonly used subgroups of cardiovascular drugs (table II).

Analgesics were used by most persons (89%) in the excessive polypharmacy group, with a mean consumption of 1.7 drugs per person (table II, figure 1). The corresponding proportions were 76% in the polypharmacy (mean 1.2 drugs) and 54% in the non-polypharmacy (mean 0.7 drugs) groups. Regarding use of drugs for the respiratory system, a marked difference was found between the excessive polypharmacy (30%) and non-polypharmacy (7%) groups; a similar difference was found in use of drugs for the alimentary tract and metabolic disorders (77% and 26%, respectively).

The prevalence of use of psychotropics varied significantly among the polypharmacy groups, ranging from 77% in the excessive polypharmacy group (mean 1.5 drugs per person) to 42% in the polypharmacy group (mean 0.7 drugs) and 20% in the non-polypharmacy group (mean 0.3 drugs) [table II, figure 1]. Anxiolytics, sedatives and hypnotics were used by two of three (61%) persons with excessive polypharmacy and by one in three (31%) persons with polypharmacy.

Factors Associated with Polypharmacy and Excessive Polypharmacy

Multinomial logistic regression analysis indicated that the factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy are partly different (table III). Age ≥85 years (OR 2.84; 95% CI 1.41, 5.72), female gender (OR 2.43; 95% CI 1.27, 4.65) and moderate self-reported health (OR 2.05; 95% CI 1.08, 3.89) were statistically significantly associated only with excessive polypharmacy. Poor self-reported health had a significant association with both polypharmacy (OR 2.15; 95% CI 1.01, 4.59) and excessive polypharmacy (OR 6.02; 95% CI 2.55, 14.20). Of the disease states, obstructive pulmonary disease was the factor most strongly associated with polypharmacy (OR 2.79; 95% CI 1.24, 6.25) and excessive polypharmacy (OR 6.82; 95% CI 2.87, 16.20). Diabetes, depression, heart disease and pain were other disease states and symptoms significantly associated with both polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy. Hypertension was not significantly associated with outcomes in the final model, but the variable was retained in the model because it affected the ORs of the other covariates.

Discussion

This study revealed that the factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in elderly persons are not uniform. Female gender, age ≥85 years and moderate self-reported health were associated only with excessive polypharmacy, whereas poor self-reported health and certain specific disease states and symptoms were associated with both polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy. Some previous studies, defining polypharmacy as the use of five or more drugs, have reported parallel associated factors for polypharmacy.[24,33] Our study, however, is the first to report ORs separately for polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy.

Several previous studies have reported an association between polypharmacy and advanced age and female gender.[5,15,34] Interestingly, we found that female gender and age ≥85 years are actually associated only with excessive polypharmacy. Our study results also showed that poor self-reported health seems to be a significant factor associated with both polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy, whereas moderate self-reported health is associated only with excessive polypharmacy. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies,[20,33] despite the fact that the association with excessive polypharmacy has not been reported previously. It is likely that decreased self-reported health is reported because of multimorbidity. However, decreased health status might also reflect undiagnosed diseases and otherwise unsuccessful treatment. Paradoxically, there may even be underprescribing with increasing number of drugs in use.[14]

Of the disease states and symptoms, this study found that diabetes, depression, pain, heart disease and obstructive pulmonary disease are important risk factors for both polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy. These results are consistent with those of a recent study reporting that elderly persons with congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease and diabetes are more likely to have polypharmacy.[35] Current treatment guidelines for these disease states, recommending use of multiple drugs, are mainly based on evidence obtained from studies in middle-aged populations with only a small evidence base relating to care of frail elderly persons. While our results do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the appropriateness or rationality of use of medications in the study population, it is obvious that more evidence is needed on the effectiveness of drug therapies and the rational use of drugs in those aged ≥75 years.

Consistent with other studies of home-dwelling elderly persons,[21,31] we found that the most commonly used drugs in this study were cardiovascular drugs and analgesics, which were used by almost all home-dwelling elderly persons with excessive polypharmacy. The most concerning finding in our study was the high use of psychotropics. Previous studies have shown that the use of psychotropics tends to increase with aging and with polypharmacy, which calls for a thorough assessment of the actual need for these drugs.[6,36] With regard to total medication use in this study, we noted that each therapeutic group constituted about the same proportion of total medications used in all three study groups. This finding suggests that polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy cannot be explained by increased use of any specific group of drugs.

Our results showed that persons with polypharmacy or excessive polypharmacy used about three drugs per diagnosis. Obviously this is not a measure of treatment rationality, but the findings emphasize the need for reassessment of medication so that it is based on proper diagnosis. Evidence for the rationality of combination therapy in the elderly is still mostly lacking. While it may not always be reasonable to avoid polypharmacy, especially in patients with several chronic diseases, polypharmacy is often a potential risk factor for medication problems. For example, the more drugs elderly persons use, the higher the risk of receiving potentially interacting drugs.[19] A recent study found that elderly persons taking ten or more drugs were taking an average of two inappropriate drugs.[37] Polypharmacy has also been shown to predict hospital readmission related to adverse drug reactions.[38] Medication regimens need to be assessed regularly to identify potential drug-related problems, and especially inappropriate drug use. Such regular medication assessments can improve overall medication[39,40] and reduce drug-related errors[41] and drug costs.[42]

Methodological Considerations

The information about medication used in this study was based on the subjects’ own report, drug containers and prescriptions. The reliability of this information was improved by checking medications in medical records and consulting family members and home-care personnel. The data concerning diagnoses can also be considered reliable, as these diagnoses were made by specialized clinicians according to current clinical guidelines and consensus meetings. The absence of a clinical examination by a physician in the follow-up in 2003 did not allow a comparison of the diagnoses and therefore a cross-sectional design that included only baseline data was used. The high participation rate (86%) allows generalization of the findings to the target population.

There is no agreement on the definition of polypharmacy or excessive polypharmacy. Earlier studies have mostly used four or five drugs as a cut-off point for polypharmacy.[14,23,33,41] In light of the expanded treatment options available for elderly persons, we chose a higher cut-off point for polypharmacy, defining it as the use of six to nine drugs concomitantly. For excessive polypharmacy, there is as yet no consensus or commonly used cut-off point. Some recent studies have used the same definition, ten or more drugs in use concomitantly, as was used in our study.[15,37,43]

One major limitation of our study is that our data originated from the late 1990s, which raises the question about generalizability of study results to the present day. In addition, direct comparisons with previously reported prevalences of polypharmacy are not appropriate because the studies differ with regard to whether they included only prescription drugs or also nonprescription drugs, vitamins and herbals. However, longitudinal analyses of drug use in Nordic countries show that there were significant increases in use of drugs in the elderly population during the 1980s.[44–46] In the 1990s, use of drugs continued to increase, apparently because of new opportunities in the drug treatment of elderly persons.[31] Our cross-sectional study of home-dwelling elderly was conducted in 1998 and found prevalences of 34% for polypharmacy and 23% for excessive polypharmacy. Since then, the trend for increasing drug use has continued, as shown in the 5-year follow-up study.[6] However, there is no reason to believe that the results of the regression analysis would have been different if more recent data had been used. This is supported by the results of some previous studies that found similar variables associated with polypharmacy as were observed in this study.[10,24,33,46]

Conclusions and Implications

The factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy are not uniform. Poor self-reported health, female gender and age ≥85 years are important factors associated with excessive polypharmacy. Of disease states and symptoms, diabetes, depression, pain, heart disease and obstructive pulmonary disease were associated with both polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy. The mean number of drugs per diagnosis was unexpectedly high in all study groups.

These findings point to the need for more attention to be paid to elderly persons at risk of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy. In order to minimize the harms and maximize the benefits of drug treatment, the need for and effectiveness of medications should be assessed at regular intervals, taking into account the diagnosis and the actual outcomes of treatment.

References

Fulton MM, Allen ER. Polypharmacy in the elderly: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2005; 17: 123–32

Frazier SC. Health outcomes and polypharmacy in elderly individuals: an integrated literature review. J Gerontol Nurs 2005; 31: 4–11

Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007; 5: 345–51

Klaukka T, Mäkelä M, Sipilä J, et al. Multiuse of medicines in Finland. Med Care 1993; 31: 445–50

Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T, et al. Use of medications and polypharmacy are increasing among the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 2002; 55: 809–17

Jyrkkä J, Vartiainen L, Hartikainen S, et al. Increasing use of medicines in elderly persons: a five-year follow-up of the Kuopio 75+ Study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 62: 151–8

Thomas HF, Sweetnam PM, Janchawee B, et al. Polypharmacy among older men in South Wales. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 55: 411–5

Kennerfalk A, Ruigomez A, Wallander MA, et al. Geriatric drug therapy and healthcare utilization in the United Kingdom. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36: 797–803

Chen YF, Dewey ME, Avery AJ, et al. Self-reported medication use for older people in England and Wales. J Clin Pharm Ther 2001; 26: 129–40

Veehof L, Stewart R, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, et al. The development of polypharmacy: a longitudinal study. Fam Pract 2000; 17: 261–7

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003; 289: 1107–16

Green JL, Hawley JN, Rask KJ. Is the number of prescribing physicians an independent risk factor for adverse drug events in an elderly outpatient population? Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007; 5: 31–9

Jörgensen T, Johansson S, Kennerfalk A, et al. Prescription drug use, diagnoses, and healthcare utilization among the elderly. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35: 1004–9

Kuijpers MA, van Marum RJ, Egberts AC, et al. Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 65: 130–3

Linton A, Garber M, Fagan NK, et al. Examination of multiple medication use among TRICARE beneficiaries aged 65 years and older. J Manag Care Pharm 2007; 13: 155–62

Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO). Medicines consumption in the Nordic countries 1999–2003. Copenhagen: NOMESCO, 2004

Hajjar ER, Hanlon JT, Sloane RJ, et al. Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1518–23

Cannon KT, Choi MM, Zuniga MA. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients receiving home health care: a retrospective data analysis. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006; 4: 134–43

Åstrand B, Åstrand E, Antonov K, et al. Detection of potential drug interactions: a model for a national pharmacy register. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 62: 749–56

Rosholm JU, Christensen K. Relationship between drug use and self-reported health in elderly Danes. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 53: 179–83

Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard EM. The consumption of drugs by 75-year-old individuals living in their own homes. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000; 56: 501–9

Aparasu RR, Mort JR, Brandt H. Polypharmacy trends in office visits by the elderly in the United States, 1990 and 2000. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2005; 1: 446–59

Haider SI, Johnell K, Thorslund M, et al. Analysis of the association between polypharmacy and socioeconomic position among elderly aged ≥77 years in Sweden. Clin Ther 2008; 30: 419–27

Bjerrum L, Sogaard J, Hallas J, et al. Polypharmacy: correlations with sex, age and drug regimen: a prescription database study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 54: 197–202

Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard EM. Drug therapy in the elderly: what doctors believe and patients actually do. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 51: 615–22

Sorensen L, Stokes JA, Purdie DM, et al. Medication management at home: medication-related risk factors associated with poor health outcomes. Age Ageing 2005; 34: 626–32

Alarcon T, Barcena A, Gonzalez-Montalvo JI, et al. Factors predictive of outcome on admission to an acute geriatric ward. Age Ageing 1999; 28: 429–32

Ziere G, Dieleman JP, Hofman A, et al. Polypharmacy and falls in the middle age and elderly population. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 61: 218–23

Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Harrold LR, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events among older adults in the ambulatory setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52: 1349–54

Fialová D, Topinková E, Gambassi G, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use among elderly home care patients in Europe. JAMA 2005; 293: 1348–58

Haider SI, Johnell K, Thorslund M, et al. Trends in polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions across educational groups in elderly patients in Sweden for the period 1992–2002. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 45: 643–53

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

Junius-Walker U, Theile G, Hummers-Pradier E. Prevalence and predictors of polypharmacy among older primary care patients in Germany. Fam Pract 2007; 24: 14–9

Jensen E, Schroll M. A 30-year survey of drug use in the 1914 birth cohort in Glostrup County, Denmark: 1964–1994. Aging Clin Exp Res 2008; 20: 145–52

Kuzuya M, Masuda Y, Hirakawa Y, et al. Underuse of medications for chronic diseases in the oldest of community-dwelling older frail Japanese. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 598–605

Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T, et al. Psychotropics among the home-dwelling elderly: increasing trends. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17: 874–83

Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, et al. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 1516–23

Ruiz B, Garcia M, Aguirre U, et al. Factors predicting hospital readmissions related to adverse drug reactions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 64: 715–22

Fillit HM, Futterman R, Orland BI, et al. Polypharmacy management in Medicare managed care: changes in prescribing by primary care physicians resulting from a program promoting medication reviews. Am J Manag Care 1999; 5: 587–94

Saltvedt I, Spigset O, Ruths S, et al. Patterns of drug prescription in a geriatric evaluation and management unit as compared with the general medical wards: a randomised study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61: 921–8

Denneboom W, Dautzenberg MG, Grol R, et al. Analysis of polypharmacy in older patients in primary care using a multidisciplinary expert panel. Br J Gen Pract 2006; 56: 504–10

Zarowitz BJ, Stebelsky LA, Muma BK, et al. Reduction of high-risk polypharmacy drug combinations in patients in a managed care setting. Pharmacotherapy 2005; 25: 1636–45

Rajska-Neumann A, Wieczorowska-Tobis K. Polypharmacy and potential inappropriateness of pharmacological treatment among community-dwelling elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2007; 44Suppl. 1: 303–9

Lernfelt B, Samuelsson O, Skoog I, et al. Changes in drug treatment in the elderly between 1971 and 2000. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 59: 637–44

Klaukka T, Martikainen J, Kalimo E. Drug utilization in Finland 1964–1987. Publications of the social Insurance Institution M:71. Helsinki: Social Insurance Institution, 1990

Jylhä M. Ten-year change in the use of medical drugs among the elderly — a longitudinal study and cohort comparison. J Clin Epidemiol 1994; 47: 69–79

Acknowledgements

The Kuopio 75+ Study was funded by the Nordic Red Feather of the Lions. Subsequent financial support for data analysis was obtained from the Kuopio University Pharmacy Fund and the Social Insurance of Finland. In addition, the study was supported by grants from the Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation, and the Orion-Farmos Research Foundation. The funders had no role in the design of the Kuopio 75+ Study or the preparation of this article.

The authors would like to thank the dedicated research staff who collected and saved the data. The authors are also grateful to Ms Päivi Heikura for her role in maintaining and updating the Kuopio 75+ database. In addition, the authors would like to thank statistician Piia Lavikainen for her advice regarding the statistical analysis.

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jyrkkä, J., Enlund, H., Korhonen, M.J. et al. Patterns of Drug Use and Factors Associated with Polypharmacy and Excessive Polypharmacy in Elderly Persons. Drugs Aging 26, 493–503 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200926060-00006

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200926060-00006