Abstract

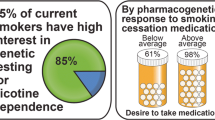

OBJECTIVE: Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death nationally. Emerging research may lead to improved smoking cessation treatment options, including tailoring treatment by genotype. Our objective was to assess primary care physicians’ attitudes toward new genetic-based approaches to smoking treatment.

DESIGN AND SETTING: A 2002 national survey of primary care physicians. Respondents were randomly assigned a survey including 1 of 2 scenarios: a scenario in which a new test to tailor smoking treatment was described as a “genetic” test or one in which the new test was described as a “serum protein” test.

PARTICIPANTS: The study sample was randomly drawn from all U.S. primary care physicians in the American Medical Association Masterfile (e.g., those with a primary specialty of internal medicine, family practice, or general practice). Of 2,000 sampled physicians, 1,120 responded, yielding a response rate of 62.3%.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: Controlling for physician and practice characteristics, describing a new test as “genetic” resulted in a regression-adjusted mean adoption score of 73.5, compared to a score of 82.5 for a nongenetic test, reflecting an 11% reduction in physicians’ likelihood of offering such a test to their patients.

CONCLUSIONS: Merely describing a new test to tailor smoking treatment as “genetic” poses a significant barrier to physician adoption. Considering national estimates of those who smoke on a daily basis, this 11% reduction in adoption scores would translate into 3.9 million smokers who would not be offered a new genetic-based treatment for smoking. While emerging genetic research may lead to improved smoking treatment, the potential of novel interventions will likely go unrealized unless barriers to clinical integration are addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2000. MMWR. 2002;51:642–5.

Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD000146.

Hughes JR, Goldstein MG, Hurt RD, Shiffman S. Recent advances in the pharmacotherapy of smoking. JAMA. 1999;281:72–6.

Lerman C, Niaura R. Applying genetic approaches to the treatment of nicotine dependence. Oncogene. 2002;21:7412–20.

Heath AC, Martin NG. Genetic models for the natural history of smoking: evidence for a genetic influence on smoking persistence. Addict Behav. 1993;18:19–34.

Kendler KS, Neale MC, Sullivan P, Corey LA, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. A population-based twin study in women of smoking initiation and nicotine dependence. Psychol Med. 1999;29:299–308.

Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. The genetic epidemiology of smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(suppl 2):S51-S57.

True WR, Xian H, Scherrer JF, et al. Common genetic vulnerability for nicotine and alcohol dependence in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:655–61.

Lerman C, Berrettini W. Elucidating the role of genetic factors in smoking behavior and nicotine dependence. Am J Med Genet. 2003;118B:48–54.

Xu C, Goodz S, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 genetic variation and potential consequences. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1245–56.

Lerman C, Caporaso NE, Audrain J, et al. Evidence suggesting the role of specific genetic factors in cigarette smoking. Health Psychol. 1999;18:14–20.

Lerman C, Caporaso NE, Bush A, et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase gene variant and smoking behavior. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:518–20.

Noble EP, St Jeor ST, Ritchie T, et al. D2 dopamine receptor gene and cigarette smoking: a reward gene? Med Hypotheses. 1994;42:257–60.

Sabol SZ, Nelson ML, Fisher C, et al. A genetic association for cigarette smoking behavior. Health Psychol. 1999;18:7–13.

Spitz MR, Shi H, Yang F, et al. Case-control study of the D2 dopamine receptor gene and smoking status in lung cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:358–63.

Sullivan PF, Jiang Y, Neale MC, Kendler KS, Straub RE. Association of the tryptophan hydroxylase gene with smoking initiation but not progression to nicotine dependence. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:479–84.

Lerman C, Shields PG, Wileyto EP, et al. Pharmacogenetic investigation of smoking cessation treatment. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:627–34.

Lerman C, Wileyto EP, Patterson F, et al. The functional mu opiod receptor (OPRM1) Asn40Asp variant predicts short-term response to nicotine replacement therapy in a clinical trial. Pharmacogenomics J. 2004;4:184–92.

Evans WE, Relling MV. Pharmacogenomics: translating functional genomics into rational therapeutics. Science. 1999;286:487–91.

Poolsup N, Li Wan Po A, Knight TL. Pharmacogenetics and psychopharmacotherapy. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25:197–220.

Roses AD. Pharmacogenetics and the practice of medicine. Nature. 2000;405:857–65.

Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ntzani E, Ioannidis JP. Translation of highly promising basic science research into clinical applications. Am J Med. 2003;114:477–84.

Crowley WF Jr. Translation of basic research into useful treatments: how often does it occur? Am J Med. 2003;114:503–5.

Shields AE, Lerman C, Sallivan PF. Translating emerging research on the genetics of smoking into clinical practice: ethical and social considerations. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2004;6:675–88.

Carey TS, Garrett J. Patterns of ordering diagnostic tests for patients with acute low back pain. The North Carolina Back Pain Project. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:807–14.

Mandelblatt JS, Berg CD, Meropol NJ, et al. Measuring and predicting surgeons’ practice styles for breast cancer treatment in older women. Med Care. 2001;39:228–42.

Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283:1715–22.

Church AH. Estimating the effect of incentives on mail survey response rates: a meta-analysis. Public Opin Q. 1993;57:62–79.

Singer E, Groves RM, Corning AD. Differential incentives: beliefs about practices, perceptions of equity, and effects on survey participation. Public Opin Q. 1999;63:251–60.

Area Resource File (ARF). February 2003. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.arfsys.com. Accessed January 2004.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Volume 1: Summary of National Findings. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD; 2002.

Emery J, Watson E, Rose P, Andermann A. A systematic review of the literature exploring the role of primary care in genetic services. Fam Pract. 1999;16:426–45.

Suchard MA, Yudkin P, Sinsheimer JS. Are general practitioners willing and able to provide genetic services for common diseases?. J Genet Couns. 1999;8:301–11.

National Human Genome Research Institute. Search the NHGRI Policy and Legislation Database by U.S. State. Available at: http://222.genome.gov/policyEthics/LegDatabase/pubMapSearch.cfm. Accessed June 2004.

Stamp MJ, David SP. Are family physicians willing to use pharmacogenetics for smoking cessation therapy? Fam Med. 2003;35:83.

Rogers E. Diffusion of Innovations. New York, NY: Free Press of Glencoe; 1962.

Hofman KL, Tambor ES, Chase GA, Geller G, Faden RR, Holtzman NA. Physicians’ knowledge of genetics and genetic tests. Acad Med. 1993;68:625–32.

Demmer LA, O’Neill MJ, Roberts AE, Clay MC. Knowledge of ethical standards in genetic testing among medical students, residents, and practicing physicians. JAMA. 2000;284:2595–6.

Ford CA, Millstein SG. Delivery of confidentiality assurances to adolescents by primary care physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:505–9.

Hayflick SJ, Eiff MP, Carpenter L, Steinberger J. Primary care physicians’ utilization and perceptions of genetics services. Genet Med. 1998;1:13–21.

James C, Geller G, Bernhardt BA, Doksum T, Holtzman NA. Are practicing and future physicians prepared to obtain informed consent? The case of genetic testing for the susceptibility to breast cancer. Community Genet. 1998;1:203–12.

Carnes M, Howell T, Rosenberg M, Francis J, Hildebrand C, Knuppel J. Physicians vary in approches to the clinical management of delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:234–9.

Haghbin Z, Streltzer J, Danko GP. Assisted suicide and AIDS patients. A survey of physician’ attitudes. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:18–23.

Hodges MO, Tolle SW, Stocking C, Cassel CK. Tube feeding. Internists’ attitudes regarding ethical obligations. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1013–20.

Mallory MD, Shay DK, Garrett J, Bordley WC. Bronchiolitis management preferences and the influence of pulse oximetry and respiratory rate on the decision to admit. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e45-e51.

Menasha JD, Schechter C, Willner J. Genetic testing: a physician’s perspective. Mount Sinai J Med. 2000;67:144–51.

Slome LR, Mitchell TF, Charlebois E, Benevedes JM, Abrams DI. Physician-assisted suicide and patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:417–21.

Swarztrauber K, Vickrey BG, Mittman BS. Physicians’ preferences for specialty involvement in the care of patients with neurological conditions. Med Care. 2002;40:1196–209.

Roberts JS. Anticipating response to predictive genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease: a survey of first-degree relatives. Gerontologist. 2000;40:43–52.

Baker TB, Hatsukami DK, Lerman C, O’Malley SS, Shields AE, Fiore MC. Transdisciplinary science applied to the evaluation of treatments for tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:S89-S99.

Clayton RR, Scutchfield FD, Wyatt SW. Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project: a new gold standard in prevention science requires new transdisciplinary thinking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1964–5.

American Society of Human Genetics Social Issues Subcommittee on Familial Disclosure. ASHG statement: professional disclosure of familial genetic information. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:474–83.

Collins FS. Preparing health professionals for the genetic revolution. JAMA. 1997;278:1285–6.

Stephenson J. As discoveries unfold, a new urgency to bring genetic literacy to physicians. JAMA. 1997;278:1225–6.

Malek JI, Geller G, Sugarman J. Talking about cases in bioethics: the effect of an intensive course on health care professionals. J Med Ethics. 2000;26:131–6.

Freedman AN, Wideroff L, Olson L, et al. US physicians’ attitudes toward genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Am J Med Genet. 2003;120A:63–71.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest related to this study.

This work is supported by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (AES) and a Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center grant (CL), funded by the National Cancer Institute and National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50 CA/DA84718).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shields, A.E., Blumenthal, D., Weiss, K.B. et al. Barriers to translating emerging genetic research on smoking into clinical practice. J GEN INTERN MED 20, 131–138 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30429.x

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30429.x