-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lorraine Culley, Caroline Law, Nicky Hudson, Elaine Denny, Helene Mitchell, Miriam Baumgarten, Nick Raine-Fenning, The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives: a critical narrative review, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 19, Issue 6, November/December 2013, Pages 625–639, https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt027

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Endometriosis is a chronic condition affecting between 2 and 17% of women of reproductive age. Common symptoms are chronic pelvic pain, fatigue, congestive dysmenorrhoea, heavy menstrual bleeding and deep dyspareunia. Studies have demonstrated the considerable negative impact of this condition on women's quality of life (QoL), especially in the domains of pain and psychosocial functioning. The impact of endometriosis is likely to be exacerbated by the absence of an obvious cause and the likelihood of chronic, recurring symptoms. The aims of this paper are to review the current body of knowledge on the social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives; to provide insights into women's experience of endometriosis; to provide a critical commentary on the current state of knowledge and to make recommendations for future psycho-social research.

The review draws on a method of critical narrative synthesis to discuss a heterogeneous range of both quantitative and qualitative studies from several disciplines. This included a systematic search, a structured process for selecting and collecting data and a systematic thematic analysis of results.

A total of 42 papers were included in the review; 23 used quantitative methods, 16 used qualitative methods and 3 were mixed methods studies. The majority of papers came from just four countries: UK (10), Australia (8), Brazil (6) and the USA (5). Key categories of impact identified in the thematic analysis were diagnostic delay and uncertainty; ‘QoL’ and everyday activities; intimate relationships; planning for and having children; education and work; mental health and emotional wellbeing and medical management and self-management.

Endometriosis has a significant social and psychological impact on the lives of women across several domains. Many studies have methodological limitations and there are significant gaps in the literature especially in relation to a consideration of the impact on partners and children. We recommend additional prospective and longitudinal research utilizing mixed methods approaches and endometriosis-specific instruments to explore the impact of endometriosis in more diverse populations and settings. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to develop and evaluate interventions for supporting women and partners living with this chronic and often debilitating condition.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic condition affecting women of reproductive age. It is characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus which induces a local inflammatory response (Kennedy et al., 2005; de Nardi and Ferrero, 2011). It is an enigmatic condition; the aetiology is uncertain and contested (Damewood et al., 1997; World Endometriosis Society and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation, 2012). Common symptoms are chronic pelvic pain, fatigue, congestive dysmenorrhoea, heavy menstrual bleeding and deep dyspareunia (Lemaire, 2004; de Nardi and Ferrero, 2011), and it is suggested that 47% of infertile women have endometriosis (Meuleman et al., 2009). The prevalence of endometriosis is difficult to assess but has been estimated at between 2 and 17% of the female population (Damewood et al., 1997; Eskenazi and Warner, 1997; Bernuit et al., 2011). There is no cure for endometriosis and so management focuses on symptom relief. This can involve a range of interventions including analgesics, hormonal therapy, both minimally invasive and radical surgery, and, where relevant, fertility treatment, with varying rates of success (European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, 2013).

Given the chronic nature of endometriosis, the potential impact on fertility and intimate relationships, the delays in diagnosis and the problematic experiences of care (Dancet et al., 2012), the social psychological impact of endometriosis on women is worthy of attention. Furthermore, there are very significant costs associated with endometriosis. A recent large-scale multicentre study of the economic costs of endometriosis revealed substantial direct and indirect costs, with annual healthcare expenditure comparable with that of other major chronic conditions such as diabetes (Simoens et al., 2012). Endometriosis is therefore of considerable importance both directly in terms of its potentially negative impact on the large number of women affected by the condition and indirectly on healthcare systems and society.

The aims of this paper are to review the current body of knowledge on the social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives; to provide insights into women's experience of endometriosis; to provide a critical commentary on the current state of knowledge and to make recommendations for future psycho-social research. The research question is: ‘What is the impact of endometriosis on women's lives and how has this been studied?’

Methods

To meet these objectives we adopted a method of review which involves an interpretive process and which allows the inclusion of a diversity of questions and studies, both quantitative and qualitative, from a range of disciplines. The review therefore draws on a method of critical narrative synthesis (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006; Popay et al., 2006) rather than a classic systematic review methodology. We have, however, adhered to the PRISMA principles as far as applicable for this type of review (Moher et al., 2009) and our reporting broadly follows this approach.

Information sources and search strategy

In February 2012, a systematic search of 13 health, medical, multidisciplinary, social science and psychology-specific databases was conducted. Appropriate search terms were constructed by reviewing abstracts, titles and keywords from a sample of papers relating to the socio-psychological impact of endometriosis known to the authors. As there appeared to be little homogeneity in the terminology used a decision was made to use ‘endometriosis’ as the sole search term for the social science and psychology-specific databases to ensure an inclusive approach. Sixteen further search terms were subsequently combined with ‘endometriosis’ when searching health, medical and multidisciplinary databases in order to limit the results to papers relevant to the review. Table I shows the databases searched and the search terms used.

Literature review databases and search terms.

| Disciplines . | Databases accessed . | Search terms used . |

|---|---|---|

| Social science and psychology specific | Social Science Citation Index Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts International Bibliography of Social Sciences PsycINFO PsycARTICLES | Endometriosis |

| Health, medical and multi-disciplinary | Pubmed Academic Search Premier CINAHL Plus British Nursing Index Scopus Cochrane Library Ingenta Connect CSA Illumina | Endometriosis AND (feel OR cope OR stress OR emotion* OR distress OR quality OR experien* OR impact OR psycho* OR qualitative OR depression OR anxiety OR affect OR coping OR social OR socio*) |

| Disciplines . | Databases accessed . | Search terms used . |

|---|---|---|

| Social science and psychology specific | Social Science Citation Index Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts International Bibliography of Social Sciences PsycINFO PsycARTICLES | Endometriosis |

| Health, medical and multi-disciplinary | Pubmed Academic Search Premier CINAHL Plus British Nursing Index Scopus Cochrane Library Ingenta Connect CSA Illumina | Endometriosis AND (feel OR cope OR stress OR emotion* OR distress OR quality OR experien* OR impact OR psycho* OR qualitative OR depression OR anxiety OR affect OR coping OR social OR socio*) |

Literature review databases and search terms.

| Disciplines . | Databases accessed . | Search terms used . |

|---|---|---|

| Social science and psychology specific | Social Science Citation Index Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts International Bibliography of Social Sciences PsycINFO PsycARTICLES | Endometriosis |

| Health, medical and multi-disciplinary | Pubmed Academic Search Premier CINAHL Plus British Nursing Index Scopus Cochrane Library Ingenta Connect CSA Illumina | Endometriosis AND (feel OR cope OR stress OR emotion* OR distress OR quality OR experien* OR impact OR psycho* OR qualitative OR depression OR anxiety OR affect OR coping OR social OR socio*) |

| Disciplines . | Databases accessed . | Search terms used . |

|---|---|---|

| Social science and psychology specific | Social Science Citation Index Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts International Bibliography of Social Sciences PsycINFO PsycARTICLES | Endometriosis |

| Health, medical and multi-disciplinary | Pubmed Academic Search Premier CINAHL Plus British Nursing Index Scopus Cochrane Library Ingenta Connect CSA Illumina | Endometriosis AND (feel OR cope OR stress OR emotion* OR distress OR quality OR experien* OR impact OR psycho* OR qualitative OR depression OR anxiety OR affect OR coping OR social OR socio*) |

Process for selecting papers

Eligibility criteria

The review was designed to take a broad overview of the topic, going beyond conventional ‘quality-of-life’ studies, to include the contribution of work from several disciplines including sociology, psychology and anthropology and both qualitative and quantitative approaches, to provide a more comprehensive and holistic picture of the impact of endometriosis on the lives of women.

Inclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed, English-language journal articles that examined the social and psychological impact of endometriosis, its treatment and management were included in the review. No age limits on participants or date restrictions were imposed.

Exclusion criteria

Papers solely investigating the prevalence, medical or clinical features of endometriosis or reporting clinical effectiveness of treatments were excluded. Reviews, opinion pieces, commentaries and clinical cases studies which did not include new data were also excluded.

Screening

Documents identified through database searching were screened and assessed for eligibility. First, duplicates and ineligible publication types were removed. Following this, titles and, if needed, abstracts and full texts were screened by two authors independently (H.M. and C.L.) based on clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and those deemed ineligible were removed.

Quality assessment

A quality assurance tool appropriate for both quantitative and qualitative studies was applied to full text papers (Shepherd et al., 2006). This included seven criteria and, consistent with its prior use, papers were required to achieve a score of at least four out of seven to be included (Dancet et al., 2010). Three authors quality assured the papers (by L.C., E.D. and C.L.); papers identified for potential exclusion were then reviewed by a fourth author (N.H.) and a decision was made.

Data collection process

A data extraction sheet was developed and applied to each paper to independently extract data (by all authors). Papers which met the inclusion criteria and quality assessment criteria were examined comprehensively and information from each paper was collated in an Excel spreadsheet recording: authors; publication date; research setting; research aims; research design; participants; sample size; recruitment method; data analysis methods; key findings; key themes and methodological limitations including risk of bias. For each paper, one author acted as the primary reviewer and a second author verified the data extraction. Any discrepancies were discussed between reviewers and consensus was achieved.

Analysis

To report on paper findings, analysis and organization of the extracted data were conducted according to principles of systematic thematic analysis (Dixon-Woods et al., 2005; Braun and Clarke, 2006; Ward et al., 2009). Stage one included a process of ‘open coding’ which was used by all seven authors to organize data from each paper during data extraction. Open coding refers to a process of selecting and naming significant issues which arise from a body of data. This process was carried out for all 42 papers. Open codes were then collated by one author (C.L.) and organized under higher order categories, or substantial themes, according to standard principles of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). For example, the codes ‘stress’, ‘self-esteem’, ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’ and ‘isolation’ were grouped under the substantial theme ‘mental health and emotional wellbeing’. The resultant framework of substantial themes was discussed and refined by three authors (L.C., C.L. and N.H.) and the final seven substantial themes were agreed. The extracted data were then reorganized according to these substantial themes, and they were employed as the structuring framework for the narrative summary.

To report on paper characteristics, quantitative data on the characteristics of papers were collated and counted. These are reported in the section ‘Characteristics of papers’.

Results: search, screening and selection

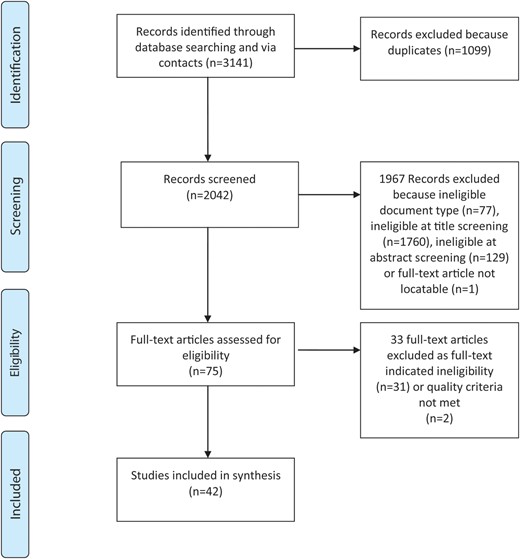

The database searches resulted in a total of 1963 papers and 2 further papers were identified via contacts while duplicates and ineligible document types were excluded. After screening the titles, 1760 papers were excluded, and after screening the abstracts, 129 papers were excluded. Following this full text papers were sought. One paper (Kumar et al., 2010) was not included as it could not be located: an inter-library loan request was unsuccessful as a supplier could not be located, and the author did not respond to email requests. After screening full texts, 31 papers were excluded, and after quality assuring full texts, 2 papers were excluded, resulting in 42 papers for inclusion. An overview of the search results and screening criteria is summarized in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of papers

Given the wide-ranging nature of this review, considerable variation was found in research aims and questions, methodology, sample size and outcome measures. Table II provides an overview of the heterogeneity of the data using the variables: author/date/country; study aim/research question; research design and method and sample. In some instances data from one study were reported on in two or more papers, and therefore the 42 papers do not represent 42 separate studies or samples.

Paper characteristics.

| Authors, year of publication, country of analysis and participants (if different) . | Study aim/research question . | Research design and methods . | Sample . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballard et al. (2006), UK | To investigate the possible reasons for a delayed diagnosis of endometriosis and the impact of delay on women's experiences of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 28 women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Bernuit et al. (2011), Germany (analysis), cross country (participants) | To elucidate the differences in diagnoses and treatment experiences of women and to assess the impact of endometriosis on their QoL | Quantitative Author devised online survey | 21 749 women of which 5.1% had surgically or non-surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Recruited via online market research company |

| Butt and Chesla (2007), USA | To investigate the responses in couples' relationships to living with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 13 women with endometriosis and 13 male partners of women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Chene et al. (2012), France | To compare pain symptoms and the QoL between epiphenomenon and endometriosis disease | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; simplified sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; pain VAS | 437 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Christian (1993), USA | To determine the relationship between women's symptoms of endometriosis and self-esteem | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; RSES | 23 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Cox et al. (2003a), Australia | To identify the information and support needs of women with endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire | 465 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003b), Australia | To identify information needs of women facing laparoscopy for endometriosis | Qualitative Focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003c), Australia | To determine women's needs for information related to laparoscopy for endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire and focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Denny (2004a), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 15 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2004b), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with the pain of endometriosis and examine delay in the diagnosis of the disease | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2009), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis in a prospective study over a 1-year period | Qualitative Interviews and diaries | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2007), UK | To determine how much of an impact endometriosis-associated dyspareunia has on the lives and relationships of women | Mixed Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2008), UK | To elicit the experience of endometriosis and the impact on women's lives; to explore the experience of women with endometriosis in the primary care setting | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Eriksen et al. (2008), Denmark | To compare patients with endometriosis with and without pain symptoms to see if they differed on four psychological parameters (coping, emotional inhibition, depression and anxiety); to examine the effects of pain caused by endometriosis on psychosocial functioning | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; CSQ; CECS; BDI; State Anxiety Scale of the STAI | 63 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic. |

| Fagervold et al. (2009), Norway | To investigate longitudinally the consequences of endometriosis in women diagnosed with the disease 15 years ago. | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 78 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Ferrero et al. (2005), Italy | To characterize the sexual function in women with endometriosis and deep dyspareunia | Quantitative Adapted sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; GSSI; VAS | 136 women of which 96 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Fourquet et al. (2011), Puerto Rico | To quantify the impact of endometriosis-related symptoms on physical and mental health status, health-related QoL and work-related aspects | Quantitative SF-12; EHP-5; WPAI | 193 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Fourquet et al. (2010), Puerto Rico | To assess the burden of endometriosis by obtaining patient-reported outcome data describing the experience of living with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 107 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Gilmour et al. (2008), New Zealand | To explore the impact of symptomatic endometriosis on women's social and working lives | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Huntington and Gilmour (2005), New Zealand | To explore women's perceptions of living with endometriosis, its effects on their lives and the strategies used to manage their disease | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Jones et al. (2004), UK | To explore and describe the impact of endometriosis upon QoL; to identify and understand, from the patient's perspective, the areas of health-related QoL that are affected by endometriosis and to address the benefits of using a qualitative methodology for item generation in the development of disease-specific health status questionnaires | Qualitative Interviews | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Lemaire (2004), USA | To examine the frequency, severity, interference with daily life and symptom distress associated with endometriosis and to explore the relationships among symptoms, emotional distress, uncertainty and a preference for and adequacy of information | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; MUIS-C; adapted HOSI | 298 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Lorençatto et al. (2006), Brazil | To compare the prevalence of depression in women with endometriosis according to the presence or absence of pelvic pain | Quantitative BDI | 100 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Low et al. (1993), UK | To investigate the possibility of a specific psychological profile associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; EPQ; BDI; GHQ 30; STAI; GRIMS; SF-MPQ | 81 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Manderson et al. (2008), Australia | To explore whether and how women's experience of gynaecological or reproductive health problems or conditions impacted their gendered, social and personal identities | Qualitative Interviews | 40 women of which 25 had endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Markovic et al. (2008), Australia | To explore the influence of socio-demographic background and social and family norms on the illness narratives of endurance and contest among women with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Marques et al. (2004), Brazil | To assess the QoL in women with chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis and to correlate QoL with personal characteristics | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; medical records; SF-36 | 57 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Mathias et al. (1996), USA | To determine the prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in US women aged 18–50 and to examine its association with health-related QoL, work productivity and healthcare utilization | Quantitative Author devised telephone administered questionnaire, including section based on MOS | 773 women with pelvic pain of which 74 had endometriosis. Recruited via research company |

| Nnoaham et al. (2011), cross country | To assess the impact of endometriosis on health-related QoL and work productivity | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; WPAI | 1418 women of which 745 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Petrelluzzi et al. (2008), Brazil | To evaluate the perceived stress index, QoL and hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis activity in women with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain | Quantitative Pain VAS; SF-36; PSQ; salivary cortisol concentrations | 175 women of which 93 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Peveler et al. (1996), UK | To compare the groups of laparoscopy-negative pelvic pain patients and patients with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis, using measures of mood, personality and social adjustment; to investigate further the relative importance of psychological and social factors in such patients | Quantitative Pain index measure; pain VAS; BSI; EPQ; SAS | 91 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Roth et al. (2011), USA | To compare women with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis with those with chronic pelvic pain from other reasons to determine if there are any psychological variables uniquely associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Clinic devised questionnaire; BDI; BSI; MPQ; PDI | 138 women of which 30 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Seear (2009a), Australia | No explicit study aim or research question, but focuses on factors associated with delayed diagnosis of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009b), Australia | To explore the experiences of women living with endometriosis; to examine how women become experts in their own care and the ramifications of these processes for women | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009c), Australia | To examine the phenomenon of non-compliance with health advice among women diagnosed with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Sepulcri and do Amaral, (2009), Brazil | To assess depressive symptoms, anxiety and QoL in women with pelvic endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; pain VAS; BDI; HAM-D; STAI; HAM-A; WHOQOL-BREF | 104 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Siedentopf et al. (2008), Germany | To identify if (i) psychosocial factors differ in endometriosis; (ii) related psychosocial aspects alter immune markers of depression/sickness behaviour and (iii) serum immune marker may be indicative for endometriosis (last two aims not included in review) | Quantitative Blood tests; ADS; SF-36; adapted PSQ; F-SoZU | 69 women of which 38 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Simoens et al. (2012), cross country | To calculate the costs and health-related QoL of women with endometriosis-associated symptoms | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; WPAI; EuroQol-5D | 909 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Souza et al. (2011), Brazil | To compare the QoL in patients with chronic pelvic pain due to endometriosis or other reasons | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; Pain VAS; HARS; BDI | 57 women with pelvic pain of which 32 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Tripoli et al. (2011), Brazil | To evaluate the QoL of women with chronic pelvic pain with and without endometriosis | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; GRISS | 134 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Waller and Shaw (1995), UK | To investigate whether there are psychological differences between women with symptomatic as opposed to asymptomatic mild endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; BDI; STAI; GRISS | 117 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Whelan (2007), Canada (analysis), cross country (participants) | To analyse the epistemological strategies and standards used by members of an endometriosis patient community | Qualitative Focus groups and survey | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and online community |

| Authors, year of publication, country of analysis and participants (if different) . | Study aim/research question . | Research design and methods . | Sample . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballard et al. (2006), UK | To investigate the possible reasons for a delayed diagnosis of endometriosis and the impact of delay on women's experiences of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 28 women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Bernuit et al. (2011), Germany (analysis), cross country (participants) | To elucidate the differences in diagnoses and treatment experiences of women and to assess the impact of endometriosis on their QoL | Quantitative Author devised online survey | 21 749 women of which 5.1% had surgically or non-surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Recruited via online market research company |

| Butt and Chesla (2007), USA | To investigate the responses in couples' relationships to living with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 13 women with endometriosis and 13 male partners of women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Chene et al. (2012), France | To compare pain symptoms and the QoL between epiphenomenon and endometriosis disease | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; simplified sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; pain VAS | 437 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Christian (1993), USA | To determine the relationship between women's symptoms of endometriosis and self-esteem | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; RSES | 23 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Cox et al. (2003a), Australia | To identify the information and support needs of women with endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire | 465 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003b), Australia | To identify information needs of women facing laparoscopy for endometriosis | Qualitative Focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003c), Australia | To determine women's needs for information related to laparoscopy for endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire and focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Denny (2004a), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 15 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2004b), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with the pain of endometriosis and examine delay in the diagnosis of the disease | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2009), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis in a prospective study over a 1-year period | Qualitative Interviews and diaries | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2007), UK | To determine how much of an impact endometriosis-associated dyspareunia has on the lives and relationships of women | Mixed Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2008), UK | To elicit the experience of endometriosis and the impact on women's lives; to explore the experience of women with endometriosis in the primary care setting | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Eriksen et al. (2008), Denmark | To compare patients with endometriosis with and without pain symptoms to see if they differed on four psychological parameters (coping, emotional inhibition, depression and anxiety); to examine the effects of pain caused by endometriosis on psychosocial functioning | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; CSQ; CECS; BDI; State Anxiety Scale of the STAI | 63 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic. |

| Fagervold et al. (2009), Norway | To investigate longitudinally the consequences of endometriosis in women diagnosed with the disease 15 years ago. | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 78 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Ferrero et al. (2005), Italy | To characterize the sexual function in women with endometriosis and deep dyspareunia | Quantitative Adapted sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; GSSI; VAS | 136 women of which 96 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Fourquet et al. (2011), Puerto Rico | To quantify the impact of endometriosis-related symptoms on physical and mental health status, health-related QoL and work-related aspects | Quantitative SF-12; EHP-5; WPAI | 193 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Fourquet et al. (2010), Puerto Rico | To assess the burden of endometriosis by obtaining patient-reported outcome data describing the experience of living with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 107 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Gilmour et al. (2008), New Zealand | To explore the impact of symptomatic endometriosis on women's social and working lives | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Huntington and Gilmour (2005), New Zealand | To explore women's perceptions of living with endometriosis, its effects on their lives and the strategies used to manage their disease | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Jones et al. (2004), UK | To explore and describe the impact of endometriosis upon QoL; to identify and understand, from the patient's perspective, the areas of health-related QoL that are affected by endometriosis and to address the benefits of using a qualitative methodology for item generation in the development of disease-specific health status questionnaires | Qualitative Interviews | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Lemaire (2004), USA | To examine the frequency, severity, interference with daily life and symptom distress associated with endometriosis and to explore the relationships among symptoms, emotional distress, uncertainty and a preference for and adequacy of information | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; MUIS-C; adapted HOSI | 298 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Lorençatto et al. (2006), Brazil | To compare the prevalence of depression in women with endometriosis according to the presence or absence of pelvic pain | Quantitative BDI | 100 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Low et al. (1993), UK | To investigate the possibility of a specific psychological profile associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; EPQ; BDI; GHQ 30; STAI; GRIMS; SF-MPQ | 81 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Manderson et al. (2008), Australia | To explore whether and how women's experience of gynaecological or reproductive health problems or conditions impacted their gendered, social and personal identities | Qualitative Interviews | 40 women of which 25 had endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Markovic et al. (2008), Australia | To explore the influence of socio-demographic background and social and family norms on the illness narratives of endurance and contest among women with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Marques et al. (2004), Brazil | To assess the QoL in women with chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis and to correlate QoL with personal characteristics | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; medical records; SF-36 | 57 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Mathias et al. (1996), USA | To determine the prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in US women aged 18–50 and to examine its association with health-related QoL, work productivity and healthcare utilization | Quantitative Author devised telephone administered questionnaire, including section based on MOS | 773 women with pelvic pain of which 74 had endometriosis. Recruited via research company |

| Nnoaham et al. (2011), cross country | To assess the impact of endometriosis on health-related QoL and work productivity | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; WPAI | 1418 women of which 745 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Petrelluzzi et al. (2008), Brazil | To evaluate the perceived stress index, QoL and hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis activity in women with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain | Quantitative Pain VAS; SF-36; PSQ; salivary cortisol concentrations | 175 women of which 93 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Peveler et al. (1996), UK | To compare the groups of laparoscopy-negative pelvic pain patients and patients with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis, using measures of mood, personality and social adjustment; to investigate further the relative importance of psychological and social factors in such patients | Quantitative Pain index measure; pain VAS; BSI; EPQ; SAS | 91 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Roth et al. (2011), USA | To compare women with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis with those with chronic pelvic pain from other reasons to determine if there are any psychological variables uniquely associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Clinic devised questionnaire; BDI; BSI; MPQ; PDI | 138 women of which 30 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Seear (2009a), Australia | No explicit study aim or research question, but focuses on factors associated with delayed diagnosis of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009b), Australia | To explore the experiences of women living with endometriosis; to examine how women become experts in their own care and the ramifications of these processes for women | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009c), Australia | To examine the phenomenon of non-compliance with health advice among women diagnosed with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Sepulcri and do Amaral, (2009), Brazil | To assess depressive symptoms, anxiety and QoL in women with pelvic endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; pain VAS; BDI; HAM-D; STAI; HAM-A; WHOQOL-BREF | 104 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Siedentopf et al. (2008), Germany | To identify if (i) psychosocial factors differ in endometriosis; (ii) related psychosocial aspects alter immune markers of depression/sickness behaviour and (iii) serum immune marker may be indicative for endometriosis (last two aims not included in review) | Quantitative Blood tests; ADS; SF-36; adapted PSQ; F-SoZU | 69 women of which 38 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Simoens et al. (2012), cross country | To calculate the costs and health-related QoL of women with endometriosis-associated symptoms | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; WPAI; EuroQol-5D | 909 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Souza et al. (2011), Brazil | To compare the QoL in patients with chronic pelvic pain due to endometriosis or other reasons | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; Pain VAS; HARS; BDI | 57 women with pelvic pain of which 32 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Tripoli et al. (2011), Brazil | To evaluate the QoL of women with chronic pelvic pain with and without endometriosis | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; GRISS | 134 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Waller and Shaw (1995), UK | To investigate whether there are psychological differences between women with symptomatic as opposed to asymptomatic mild endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; BDI; STAI; GRISS | 117 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Whelan (2007), Canada (analysis), cross country (participants) | To analyse the epistemological strategies and standards used by members of an endometriosis patient community | Qualitative Focus groups and survey | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and online community |

ADS, Allgemeine Depressionsskala, general depression scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CSQ, Coping Styles Questionnaire; CECS, Courthald Emotional Control Scale; DFSI, Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory; EHP, Endometriosis Health Profile; EPQ, Eyesenck Personality Questionnaire; EuroQol-5D, Health-related quality of life measure; F-SoZU, Fragebogen zur sozialen Unterstü tzung (measuring social support); GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; GRIMS, Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State; GRISS, Golombok Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction; GSSI, Global Sexual Satisfaction Inventory; HAM-A, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HARS, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HOSI, Krantz Health Opinion Survey, Information Subscale; MOS, Medical Outcomes Study; MPQ, McGill Pain Questionnaire; MUIS-C, Mischel Uncertainty in Illness Scale-Community Form; PDI, Pain Disability Index; PSQ, Perceived Stress Questionnaire; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SAS, Social Adjustment Scale; SF, Short Form Health Survey; SF-MPQ, Short Form McGill Pain; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS, visual analogue scale; WHOQOL-BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument short version; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Survey.

Paper characteristics.

| Authors, year of publication, country of analysis and participants (if different) . | Study aim/research question . | Research design and methods . | Sample . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballard et al. (2006), UK | To investigate the possible reasons for a delayed diagnosis of endometriosis and the impact of delay on women's experiences of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 28 women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Bernuit et al. (2011), Germany (analysis), cross country (participants) | To elucidate the differences in diagnoses and treatment experiences of women and to assess the impact of endometriosis on their QoL | Quantitative Author devised online survey | 21 749 women of which 5.1% had surgically or non-surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Recruited via online market research company |

| Butt and Chesla (2007), USA | To investigate the responses in couples' relationships to living with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 13 women with endometriosis and 13 male partners of women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Chene et al. (2012), France | To compare pain symptoms and the QoL between epiphenomenon and endometriosis disease | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; simplified sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; pain VAS | 437 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Christian (1993), USA | To determine the relationship between women's symptoms of endometriosis and self-esteem | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; RSES | 23 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Cox et al. (2003a), Australia | To identify the information and support needs of women with endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire | 465 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003b), Australia | To identify information needs of women facing laparoscopy for endometriosis | Qualitative Focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003c), Australia | To determine women's needs for information related to laparoscopy for endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire and focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Denny (2004a), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 15 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2004b), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with the pain of endometriosis and examine delay in the diagnosis of the disease | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2009), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis in a prospective study over a 1-year period | Qualitative Interviews and diaries | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2007), UK | To determine how much of an impact endometriosis-associated dyspareunia has on the lives and relationships of women | Mixed Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2008), UK | To elicit the experience of endometriosis and the impact on women's lives; to explore the experience of women with endometriosis in the primary care setting | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Eriksen et al. (2008), Denmark | To compare patients with endometriosis with and without pain symptoms to see if they differed on four psychological parameters (coping, emotional inhibition, depression and anxiety); to examine the effects of pain caused by endometriosis on psychosocial functioning | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; CSQ; CECS; BDI; State Anxiety Scale of the STAI | 63 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic. |

| Fagervold et al. (2009), Norway | To investigate longitudinally the consequences of endometriosis in women diagnosed with the disease 15 years ago. | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 78 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Ferrero et al. (2005), Italy | To characterize the sexual function in women with endometriosis and deep dyspareunia | Quantitative Adapted sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; GSSI; VAS | 136 women of which 96 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Fourquet et al. (2011), Puerto Rico | To quantify the impact of endometriosis-related symptoms on physical and mental health status, health-related QoL and work-related aspects | Quantitative SF-12; EHP-5; WPAI | 193 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Fourquet et al. (2010), Puerto Rico | To assess the burden of endometriosis by obtaining patient-reported outcome data describing the experience of living with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 107 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Gilmour et al. (2008), New Zealand | To explore the impact of symptomatic endometriosis on women's social and working lives | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Huntington and Gilmour (2005), New Zealand | To explore women's perceptions of living with endometriosis, its effects on their lives and the strategies used to manage their disease | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Jones et al. (2004), UK | To explore and describe the impact of endometriosis upon QoL; to identify and understand, from the patient's perspective, the areas of health-related QoL that are affected by endometriosis and to address the benefits of using a qualitative methodology for item generation in the development of disease-specific health status questionnaires | Qualitative Interviews | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Lemaire (2004), USA | To examine the frequency, severity, interference with daily life and symptom distress associated with endometriosis and to explore the relationships among symptoms, emotional distress, uncertainty and a preference for and adequacy of information | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; MUIS-C; adapted HOSI | 298 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Lorençatto et al. (2006), Brazil | To compare the prevalence of depression in women with endometriosis according to the presence or absence of pelvic pain | Quantitative BDI | 100 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Low et al. (1993), UK | To investigate the possibility of a specific psychological profile associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; EPQ; BDI; GHQ 30; STAI; GRIMS; SF-MPQ | 81 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Manderson et al. (2008), Australia | To explore whether and how women's experience of gynaecological or reproductive health problems or conditions impacted their gendered, social and personal identities | Qualitative Interviews | 40 women of which 25 had endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Markovic et al. (2008), Australia | To explore the influence of socio-demographic background and social and family norms on the illness narratives of endurance and contest among women with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Marques et al. (2004), Brazil | To assess the QoL in women with chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis and to correlate QoL with personal characteristics | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; medical records; SF-36 | 57 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Mathias et al. (1996), USA | To determine the prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in US women aged 18–50 and to examine its association with health-related QoL, work productivity and healthcare utilization | Quantitative Author devised telephone administered questionnaire, including section based on MOS | 773 women with pelvic pain of which 74 had endometriosis. Recruited via research company |

| Nnoaham et al. (2011), cross country | To assess the impact of endometriosis on health-related QoL and work productivity | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; WPAI | 1418 women of which 745 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Petrelluzzi et al. (2008), Brazil | To evaluate the perceived stress index, QoL and hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis activity in women with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain | Quantitative Pain VAS; SF-36; PSQ; salivary cortisol concentrations | 175 women of which 93 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Peveler et al. (1996), UK | To compare the groups of laparoscopy-negative pelvic pain patients and patients with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis, using measures of mood, personality and social adjustment; to investigate further the relative importance of psychological and social factors in such patients | Quantitative Pain index measure; pain VAS; BSI; EPQ; SAS | 91 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Roth et al. (2011), USA | To compare women with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis with those with chronic pelvic pain from other reasons to determine if there are any psychological variables uniquely associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Clinic devised questionnaire; BDI; BSI; MPQ; PDI | 138 women of which 30 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Seear (2009a), Australia | No explicit study aim or research question, but focuses on factors associated with delayed diagnosis of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009b), Australia | To explore the experiences of women living with endometriosis; to examine how women become experts in their own care and the ramifications of these processes for women | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009c), Australia | To examine the phenomenon of non-compliance with health advice among women diagnosed with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Sepulcri and do Amaral, (2009), Brazil | To assess depressive symptoms, anxiety and QoL in women with pelvic endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; pain VAS; BDI; HAM-D; STAI; HAM-A; WHOQOL-BREF | 104 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Siedentopf et al. (2008), Germany | To identify if (i) psychosocial factors differ in endometriosis; (ii) related psychosocial aspects alter immune markers of depression/sickness behaviour and (iii) serum immune marker may be indicative for endometriosis (last two aims not included in review) | Quantitative Blood tests; ADS; SF-36; adapted PSQ; F-SoZU | 69 women of which 38 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Simoens et al. (2012), cross country | To calculate the costs and health-related QoL of women with endometriosis-associated symptoms | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; WPAI; EuroQol-5D | 909 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Souza et al. (2011), Brazil | To compare the QoL in patients with chronic pelvic pain due to endometriosis or other reasons | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; Pain VAS; HARS; BDI | 57 women with pelvic pain of which 32 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Tripoli et al. (2011), Brazil | To evaluate the QoL of women with chronic pelvic pain with and without endometriosis | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; GRISS | 134 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Waller and Shaw (1995), UK | To investigate whether there are psychological differences between women with symptomatic as opposed to asymptomatic mild endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; BDI; STAI; GRISS | 117 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Whelan (2007), Canada (analysis), cross country (participants) | To analyse the epistemological strategies and standards used by members of an endometriosis patient community | Qualitative Focus groups and survey | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and online community |

| Authors, year of publication, country of analysis and participants (if different) . | Study aim/research question . | Research design and methods . | Sample . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballard et al. (2006), UK | To investigate the possible reasons for a delayed diagnosis of endometriosis and the impact of delay on women's experiences of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 28 women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Bernuit et al. (2011), Germany (analysis), cross country (participants) | To elucidate the differences in diagnoses and treatment experiences of women and to assess the impact of endometriosis on their QoL | Quantitative Author devised online survey | 21 749 women of which 5.1% had surgically or non-surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Recruited via online market research company |

| Butt and Chesla (2007), USA | To investigate the responses in couples' relationships to living with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 13 women with endometriosis and 13 male partners of women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Chene et al. (2012), France | To compare pain symptoms and the QoL between epiphenomenon and endometriosis disease | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; simplified sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; pain VAS | 437 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Christian (1993), USA | To determine the relationship between women's symptoms of endometriosis and self-esteem | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; RSES | 23 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Cox et al. (2003a), Australia | To identify the information and support needs of women with endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire | 465 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003b), Australia | To identify information needs of women facing laparoscopy for endometriosis | Qualitative Focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic and support group |

| Cox et al. (2003c), Australia | To determine women's needs for information related to laparoscopy for endometriosis | Mixed Author devised questionnaire and focus groups | 61 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Denny (2004a), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 15 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2004b), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with the pain of endometriosis and examine delay in the diagnosis of the disease | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic, support group and snowballing |

| Denny (2009), UK | To explore women's experiences of living with endometriosis in a prospective study over a 1-year period | Qualitative Interviews and diaries | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2007), UK | To determine how much of an impact endometriosis-associated dyspareunia has on the lives and relationships of women | Mixed Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Denny and Mann (2008), UK | To elicit the experience of endometriosis and the impact on women's lives; to explore the experience of women with endometriosis in the primary care setting | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Eriksen et al. (2008), Denmark | To compare patients with endometriosis with and without pain symptoms to see if they differed on four psychological parameters (coping, emotional inhibition, depression and anxiety); to examine the effects of pain caused by endometriosis on psychosocial functioning | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; CSQ; CECS; BDI; State Anxiety Scale of the STAI | 63 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic. |

| Fagervold et al. (2009), Norway | To investigate longitudinally the consequences of endometriosis in women diagnosed with the disease 15 years ago. | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 78 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Ferrero et al. (2005), Italy | To characterize the sexual function in women with endometriosis and deep dyspareunia | Quantitative Adapted sexual satisfaction Subscale of the DSFI; GSSI; VAS | 136 women of which 96 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Fourquet et al. (2011), Puerto Rico | To quantify the impact of endometriosis-related symptoms on physical and mental health status, health-related QoL and work-related aspects | Quantitative SF-12; EHP-5; WPAI | 193 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Fourquet et al. (2010), Puerto Rico | To assess the burden of endometriosis by obtaining patient-reported outcome data describing the experience of living with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire | 107 women with endometriosis. Recruited via Endometriosis Research Programme |

| Gilmour et al. (2008), New Zealand | To explore the impact of symptomatic endometriosis on women's social and working lives | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Huntington and Gilmour (2005), New Zealand | To explore women's perceptions of living with endometriosis, its effects on their lives and the strategies used to manage their disease | Qualitative Interviews | 18 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Jones et al. (2004), UK | To explore and describe the impact of endometriosis upon QoL; to identify and understand, from the patient's perspective, the areas of health-related QoL that are affected by endometriosis and to address the benefits of using a qualitative methodology for item generation in the development of disease-specific health status questionnaires | Qualitative Interviews | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Lemaire (2004), USA | To examine the frequency, severity, interference with daily life and symptom distress associated with endometriosis and to explore the relationships among symptoms, emotional distress, uncertainty and a preference for and adequacy of information | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; MUIS-C; adapted HOSI | 298 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group |

| Lorençatto et al. (2006), Brazil | To compare the prevalence of depression in women with endometriosis according to the presence or absence of pelvic pain | Quantitative BDI | 100 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Low et al. (1993), UK | To investigate the possibility of a specific psychological profile associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; EPQ; BDI; GHQ 30; STAI; GRIMS; SF-MPQ | 81 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Manderson et al. (2008), Australia | To explore whether and how women's experience of gynaecological or reproductive health problems or conditions impacted their gendered, social and personal identities | Qualitative Interviews | 40 women of which 25 had endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Markovic et al. (2008), Australia | To explore the influence of socio-demographic background and social and family norms on the illness narratives of endurance and contest among women with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 30 women with endometriosis. Recruited via community newsletter and snowballing |

| Marques et al. (2004), Brazil | To assess the QoL in women with chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis and to correlate QoL with personal characteristics | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; medical records; SF-36 | 57 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Mathias et al. (1996), USA | To determine the prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in US women aged 18–50 and to examine its association with health-related QoL, work productivity and healthcare utilization | Quantitative Author devised telephone administered questionnaire, including section based on MOS | 773 women with pelvic pain of which 74 had endometriosis. Recruited via research company |

| Nnoaham et al. (2011), cross country | To assess the impact of endometriosis on health-related QoL and work productivity | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; SF-36; WPAI | 1418 women of which 745 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Petrelluzzi et al. (2008), Brazil | To evaluate the perceived stress index, QoL and hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis activity in women with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain | Quantitative Pain VAS; SF-36; PSQ; salivary cortisol concentrations | 175 women of which 93 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Peveler et al. (1996), UK | To compare the groups of laparoscopy-negative pelvic pain patients and patients with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis, using measures of mood, personality and social adjustment; to investigate further the relative importance of psychological and social factors in such patients | Quantitative Pain index measure; pain VAS; BSI; EPQ; SAS | 91 women of which 40 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Roth et al. (2011), USA | To compare women with chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis with those with chronic pelvic pain from other reasons to determine if there are any psychological variables uniquely associated with endometriosis | Quantitative Clinic devised questionnaire; BDI; BSI; MPQ; PDI | 138 women of which 30 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Seear (2009a), Australia | No explicit study aim or research question, but focuses on factors associated with delayed diagnosis of endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009b), Australia | To explore the experiences of women living with endometriosis; to examine how women become experts in their own care and the ramifications of these processes for women | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and snowballing |

| Seear (2009c), Australia | To examine the phenomenon of non-compliance with health advice among women diagnosed with endometriosis | Qualitative Interviews | 20 women with endometriosis. Recruitment route not stated |

| Sepulcri and do Amaral, (2009), Brazil | To assess depressive symptoms, anxiety and QoL in women with pelvic endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; pain VAS; BDI; HAM-D; STAI; HAM-A; WHOQOL-BREF | 104 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Siedentopf et al. (2008), Germany | To identify if (i) psychosocial factors differ in endometriosis; (ii) related psychosocial aspects alter immune markers of depression/sickness behaviour and (iii) serum immune marker may be indicative for endometriosis (last two aims not included in review) | Quantitative Blood tests; ADS; SF-36; adapted PSQ; F-SoZU | 69 women of which 38 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Simoens et al. (2012), cross country | To calculate the costs and health-related QoL of women with endometriosis-associated symptoms | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; WPAI; EuroQol-5D | 909 women with endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Souza et al. (2011), Brazil | To compare the QoL in patients with chronic pelvic pain due to endometriosis or other reasons | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; Pain VAS; HARS; BDI | 57 women with pelvic pain of which 32 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Tripoli et al. (2011), Brazil | To evaluate the QoL of women with chronic pelvic pain with and without endometriosis | Quantitative WHOQOL-BREF; GRISS | 134 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Waller and Shaw (1995), UK | To investigate whether there are psychological differences between women with symptomatic as opposed to asymptomatic mild endometriosis | Quantitative Author devised questionnaire; BDI; STAI; GRISS | 117 women of which 49 had endometriosis. Recruited via hospital/clinic |

| Whelan (2007), Canada (analysis), cross country (participants) | To analyse the epistemological strategies and standards used by members of an endometriosis patient community | Qualitative Focus groups and survey | 24 women with endometriosis. Recruited via support group and online community |

ADS, Allgemeine Depressionsskala, general depression scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CSQ, Coping Styles Questionnaire; CECS, Courthald Emotional Control Scale; DFSI, Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory; EHP, Endometriosis Health Profile; EPQ, Eyesenck Personality Questionnaire; EuroQol-5D, Health-related quality of life measure; F-SoZU, Fragebogen zur sozialen Unterstü tzung (measuring social support); GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; GRIMS, Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State; GRISS, Golombok Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction; GSSI, Global Sexual Satisfaction Inventory; HAM-A, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HARS, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HOSI, Krantz Health Opinion Survey, Information Subscale; MOS, Medical Outcomes Study; MPQ, McGill Pain Questionnaire; MUIS-C, Mischel Uncertainty in Illness Scale-Community Form; PDI, Pain Disability Index; PSQ, Perceived Stress Questionnaire; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SAS, Social Adjustment Scale; SF, Short Form Health Survey; SF-MPQ, Short Form McGill Pain; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS, visual analogue scale; WHOQOL-BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life instrument short version; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Survey.

Settings

Over half of the papers were published between 2005 and 2010, indicating a recent increase in research on the social and psychological impact of endometriosis. The majority of papers came from just 4 countries: UK (10), Australia (8), Brazil (6) and the USA (5). Of the remaining papers, six were from Western Europe, two from New Zealand, two from Puerto Rica and one from Canada and two papers reported on cross-country studies (Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, China, Ireland, Italy, Nigeria, Spain, UK and USA, Nnoaham et al., 2011; Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, UK and USA, Simoens et al., 2012). The majority of papers were therefore from high-income countries with developed healthcare systems. Participants were recruited from single hospitals/clinics (17), multiple hospitals/clinics (6), support groups (3) or from multiple (10) or other (4) settings, or the setting was not stated (2).

Design

Papers reported on quantitative (23), qualitative (16) and mixed methods (3) studies. The majority of papers from the UK and Australia (12 of 18) reported on qualitative studies, whereas the majority of papers from Brazil and the USA (9 of 11) reported on quantitative studies. The quantitative studies used a range of quality of life (QoL) instruments and assessments/inventories of aspects such as symptoms (including pain), wellbeing, mental health, personality, impact on work, etc. Qualitative studies predominantly used interview data collection methods, although a small number collected data via focus groups, questionnaires and diaries. Cross-sectional studies accounted for 40 papers while 2 papers reported longitudinal studies.

Participants

Sample sizes varied considerably: from 23 to ∼1110 women with endometriosis with a mean of 207 in quantitative papers; from 13 to 61 women with endometriosis with a mean of 25 in qualitative papers and from 30 to 465 women with endometriosis with a mean of 185 in mixed methods studies. Most papers reported on studies of women with confirmed (i.e. surgically diagnosed) endometriosis, although in papers where women were recruited via routes other than hospitals and clinics, diagnosis was based on self-report and not clinically verified. Thirteen papers reported on studies with broader samples where women with endometriosis were included as a subset, and where data about women without endometriosis were used for comparison. Only one study included male partners alongside women with endometriosis.

Findings on the social and psychological impact of endometriosis

Key categories identified in the thematic analysis were: diagnostic delay and uncertainty; ‘QoL’ and everyday activities; intimate relationships; planning for and having children; education and work; mental health and wellbeing and medical and self-management. Pain is a significant symptom that arises in all of these categories, and as such the impact of pain is considered throughout the findings.

Diagnostic delay and uncertainty

There were 21 papers (50%; 14 qualitative, 5 quantitative and 2 mixed methods) which reported findings relating to the impact of endometriosis in terms of diagnostic delay or uncertainty. Women with endometriosis frequently experience significant delays from symptom onset to diagnosis (Cox et al., 2003a; Denny, 2004a, b; Denny and Mann, 2008; Sepulcri and do Amaral, 2009; Fourquet et al., 2010; Bernuit et al., 2011; Nnoaham et al., 2011), ranging from 5 (Sepulcri and do Amaral, 2009) to 8.9 years (Fourquet et al., 2010). Diagnostic delays have been shown to be associated with reduced health-related QoL (Nnoaham et al., 2011). It is useful, therefore, to outline the findings regarding delayed diagnosis. The authors have distinguished between delays at the patient level and delays at the medical level (Ballard et al., 2006).

Diagnostic delay: factors at the patient level

The delay at the patient level refers to the time between symptom onset and seeking medical help. Cox et al. (2003a, b) identified an average delay of 3.8 years between symptom onset and help-seeking behaviour. It is suggested that women fail to seek medical help due to difficulty in distinguishing between normal and pathological symptoms; because they consider themselves ‘unlucky’ as opposed to ‘unwell’ and because they fear that disclosure would result in embarrassment and in them being perceived as weak (Cox et al., 2003b; Ballard et al., 2006).

Women themselves and those around them (family and friends) are frequently unaware of endometriosis as a condition (Denny, 2009; Fourquet et al., 2010). The perception of menstrual irregularities as ‘normal’ and the perception of menstrual pain as something to be endured also contribute to delay in seeking help (Cox et al., 2003b; Denny, 2004b; Ballard et al., 2006), particularly for adolescents (Manderson et al., 2008; Markovic et al., 2008). Denny (2004b) and Seear (2009a) refer to an ‘etiquette of menstruation’ (Laws, 1990) whereby in many societies, menstruation itself is perceived as something private and something to be hidden. Women may thus actively conceal their menstrual irregularities, especially from men. Others, such as mothers and friends, facilitate and encourage this concealment (Seear, 2009a). However, the influence of family and friends who are able to identify pain experiences as abnormal and encourage help seeking, as well as disrupted social roles such as in performing education or work tasks, may also serve as catalysts that shift a woman's understanding of her symptoms from being normal to pathological (Manderson et al., 2008).

Diagnostic delay: factors relating to the medical profession

Delays to diagnosis have also been identified once women have sought medical help for their symptoms and misdiagnosis is common (Denny, 2004b; Jones et al., 2004; Huntington and Gilmour, 2005; Denny and Mann, 2008). Studies demonstrate medical level delays, between help-seeking and diagnosis, of between 3.7 (Cox et al., 2003a) and 5.7 years (Denny and Mann, 2008). Delays were found to be common at the primary care level and reflect resistance to referral (Denny and Mann, 2008; Nnoaham et al., 2011). Several papers suggest that prior to diagnosis, women commonly experience repeated visits to doctors where symptoms are normalized, dismissed and/or trivialized, resulting in women feeling ignored and disbelieved (Cox et al., 2003a, b; Denny, 2004a, b, 2009; Jones et al., 2004; Ballard et al., 2006; Denny and Mann, 2008; Manderson et al., 2008; Markovic et al., 2008). Women were often initially referred to inappropriate secondary care, or were misdiagnosed, most commonly with irritable bowel syndrome or pelvic inflammatory disease (Jones et al., 2004; Ballard et al., 2006; Denny and Mann, 2008). General practitioners were reported as lacking knowledge, awareness and sympathy and displaying attitudes that perpetuate myths about endometriosis (Cox et al., 2003b; Denny, 2004b; Jones et al., 2004; Denny and Mann, 2008).

On receiving a diagnosis, symptomatic women frequently reported that they felt a sense of relief, legitimation (i.e. confirmation that their symptoms were genuine), liberation and empowerment, replacing feelings of fear and self-doubt (Cox et al., 2003a; Denny, 2004b; Huntington and Gilmour, 2005; Ballard et al., 2006; Manderson et al., 2008; Seear, 2009b). Others reported feelings of anger at the delay to diagnosis and feeling vindicated that their persistence was valid (Denny, 2004b; Denny and Mann, 2008). Diagnosis provides women with a language with which to explain their experiences and sanctions access to support services (Ballard et al., 2006). Conversely, asymptomatic women who were diagnosed opportunistically experienced a different response, often characterized by shock and disbelief (Cox et al., 2003a).

Uncertainty, which is a factor in delayed diagnosis especially at the patient level (see above), continues post-diagnosis; endometriosis is a disease characterized by uncertainty at several levels (Lemaire, 2004; Butt and Chesla, 2007; Whelan, 2007; Denny, 2009). Along with ‘diagnostic uncertainty’, women experience ‘symptomatic uncertainty’ (relating to the variability of symptoms and the trial and error approach to treatment) and ‘trajectory uncertainty’ (relating to uncertainty about their future) (Denny, 2009).

‘QoL’ and everyday activities

There were 17 papers (40%; 14 quantitative and 3 qualitative) which reported findings relating to the impact of endometriosis on QoL and everyday activities. QoL measures have been widely used in studies of endometriosis, and are discussed in several review papers (Gao et al., 2006; Jia et al., 2012). Most utilize general QoL measures [e.g. Short Form Health Survey-36 and -12 (SF-36 and SF-12)] rather than those specific to endometriosis [Endometriosis Health Profile-30 and -5 (EHP-30 and EHP-5]. A number of studies demonstrate reduced QoL among women with endometriosis (Marques et al., 2004; Petrelluzzi et al., 2008; Siedentopf et al., 2008; Bernuit et al., 2011; Tripoli et al., 2011; Chene et al., 2012), and one study demonstrated that a minority of women consider themselves to have a current state of health ‘worse than death’ (Simoens et al., 2012).

Pain is consistently reported as a central and destructive feature of life with endometriosis and several studies report a negative correlation between pain and QoL (Sepulcri and do Amaral, 2009; Nnoaham et al., 2011; Souza et al., 2011; Tripoli et al., 2011). Endometriosis symptoms, and specifically pain, have a detrimental impact on daily life and physical functioning (e.g. sleeping, eating, moving) (Jones et al., 2004; Petrelluzzi et al., 2008). Between 16% (Simoens et al., 2012) and 61% (Fourquet et al., 2011) of women experience difficulties with mobility, daily activities and/or self-care. Fourquet et al. (2011) also found that women had SF-12 scores denoting statistically significant disability in physical and mental health components, indicating that the women in this study experienced substantial disability and Nnoaham et al. (2011) found that women with endometriosis had reduced physical health compared with the normative population. Sleeping has also been found to be negatively affected by endometriosis (Fourquet et al., 2010).

Household and housekeeping activities (e.g. cooking, shopping, cleaning, gardening and childcare) are also affected (Jones et al., 2004) for between 23% (Bernuit et al., 2011) and 71% (Fourquet et al., 2010) of women with endometriosis. Bernuit et al. (2011) found that of all the women who reported that endometriosis had a negative impact on their QoL (67% of the total sample), a third (36%) said it affected their relationships with family, whereas in a smaller scale study, Fourquet et al. (2010) found that 45% of women reported a negative impact on childcare.