-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Allison Cammer, Debra Morgan, Norma Stewart, Katherine McGilton, Jo Rycroft-Malone, Sue Dopson, Carole Estabrooks, The Hidden Complexity of Long-Term Care: How Context Mediates Knowledge Translation and Use of Best Practices, The Gerontologist, Volume 54, Issue 6, December 2014, Pages 1013–1023, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt068

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

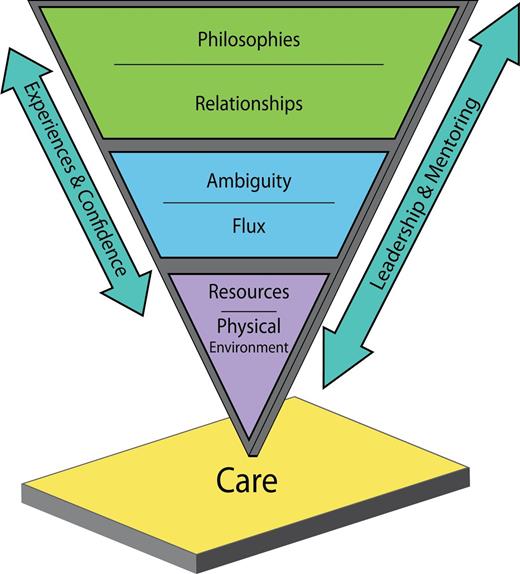

Purpose: Context is increasingly recognized as a key factor to be considered when addressing healthcare practice. This study describes features of context as they pertain to knowledge use in long-term care (LTC). Design and Methods: As one component of the research program Translating Research in Elder Care, an in-depth qualitative case study was conducted to examine the research question “How does organizational context mediate the use of knowledge in practice in long-term care facilities?” A representative facility was chosen from the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. Data included document review, direct observation of daily care practices, and interviews with direct care, allied provider, and administrative staff. Results:The Hidden Complexity of Long-Term Care model consists of 8 categories that enmesh to create a context within which knowledge exchange and best practice are executed. These categories range from the most easily identifiable to the least observable: physical environment, resources, ambiguity, flux, relationships, and philosophies. Two categories (experience and confidence, leadership and mentoring) mediate the impact of other contextual factors. Inappropriate physical environments, inadequate resources, ambiguous situations, continual change, multiple relationships, and contradictory philosophies make for a complicated context that impacts care provision. Implications: A hidden complexity underlays healthcare practices in LTC and each care provider must negotiate this complexity when providing care. Attending to this complexity in which care decisions are made will lead to improvements in knowledge exchange mechanisms and best practice uptake in LTC settings.

Context is a key factor for consideration when implementing evidence into health care practice (Glisson, 2007; Glisson et al., 2008; McCormack, 2001; Rycroft-Malone et al., 2009). To date, there has been little examination of how organizational context might influence knowledge use within long-term care (LTC) settings. This study describes features of context as they pertain to knowledge use in LTC. Against a background of population aging, a growing body of evidence on best aged care, and the preponderance of reports on poor quality care within LTC, understanding contextual factors is critical. Contextual factors that influence evidence-based practice include appropriate resources (McCormack, 2001; Rycroft-Malone, 2008), culture (Janes, Sidani, Cott, & Rappolt, 2008; McCormack, 2001; Scott, Estabrooks, Allen, & Pollock, 2008), leadership, (Rycroft-Malone, 2008), organizational support (Ring, Malcolm, Coull, Murphy-Black, & Watterson, 2005), team climate (Bower, Campbell, Bojke, & Sibbald, 2003), social networks (West, Barron, Dowsett, & Newton, 1999), organizational learning (Nutley et al., 2003), feedback systems (McCormack, 2001), receptivity to change (McCormack, 2001), coworker support, work creativity, and questioning behavior (Estabrooks et al., 2008).

A review of knowledge translation research pertaining to the care of older adults revealed a scarcity of literature on this topic, with less than 2% of the studies set in LTC facilities (Bostrom et al., 2012). Rahman, Applebaum, Schnelle, and Simmons (2012) review the reasons underlying the gap between research and practice in LTC, and concluded that translational strategies are underdeveloped and have not been systematically evaluated. Only a few studies have focused on knowledge application and capacity in LTC. Berta, Laporte, and Kachan (2010) found that from the perspective of senior clinical staff, adoption of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines was most successful where management commitment, participative leadership among staff, and the capacity to develop and adhere to a deliberate change strategy were in place. External factors of funding and practice standards also influence knowledge use (Janes, Fox, Lowe, McGilton, & Schindel-Martin, 2009). Effective interpersonal relations at all levels positively influenced knowledge exchange, including the creation of democratic and collaborative patterns of relating between leaders and practitioners. Similar findings have been reported by others (Cummings et al., 2010; Pepler et al., 2006).

In a 2008 study of knowledge utilization in dementia care, Janes and colleagues (2009) noted limited attention has been given to the influence of specific clinical contexts on evidence-based health care. “Context” has not been studied explicitly regarding clinical work with particular client populations, and has more often been addressed through organizational characteristics, such as the resources available for innovation (Kitson, 1998; Stetler, 2003) and an organization’s culture regarding research (Dobbins et al., 2002; McCormack et al., 2002). Janes and colleagues (2008) found that the nature of dementia care work was a contextual factor that weighed heavily in care aides’ clinical decision making about best practice use and set parameters for which individual and relational factors influence use of knowledge during caregiving. Focusing on specific challenges of care provision in different clinical settings may assist in advancing our full understanding of contextual enhancements or impediments to evidence-based practice (Janes et al., 2008).

Significance and Purpose

The LTC sector is an important focus because of the projected increases in the aging population and associated increasing prevalence of dementia, which is expected to lead to a 10-fold increase in the demand for LTC (Dudgeon, 2010). Building foundational knowledge about use of best practice knowledge in LTC would enhance our ability to determine what contextual factors could be modified to facilitate evidence-based care for this increasingly frail population. The purpose of this study was to explore the contextual factors that influence use of best practice knowledge in LTC settings. The study is part of a larger program of research called Translating Research in Eldercare (TREC) (Estabrooks, Hutchinson et al., 2009; Estabrooks, Squires et al. 2009). The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework underscoring TREC proposes that successful implementation of evidence into practice is a function of the complex interplay between evidence, context, and facilitation (Rycroft-Malone et al., 2002). In general, robust evidence, higher levels of facilitation, and a more favorable context are argued to increase research implementation. The framework has been widely cited and used as an organizing framework for analyses in empirical studies (Helfrich et al., 2010) primarily within acute care. This study provided an opportunity to explore the role of context in promoting knowledge use and best practice uptake in LTC.

Design and Methods

TREC is a mixed method, longitudinal program of research examining the impact of organizational context on knowledge translation and the subsequent impact of knowledge translation on outcomes for residents and staff in LTC facilities in the three Prairie Provinces of Canada. Project 1, Building context: An organizational monitoring program in LTC assessed context in 36 LTC facilities by examining facility, staff, and resident variables over time (Estabrooks, Hutchinson et al., 2009). Project 2, Building context: A case study program in LTC used in-depth qualitative case study methods to develop an explanation of the way that organizational context influences use of knowledge in practice (Rycroft-Malone et al., 2009). The research question guiding Project 2 was How does organizational context mediate the use of knowledge in practice in LTC facilities and what are the key factors that constitute organizational context as it affects knowledge use in practice? The focus of this article is the TREC Project 2 case study conducted in the province of Saskatchewan.

Sampling and Access

A “modal” LTC facility was purposively selected from the 13 Saskatchewan facilities randomly sampled for TREC Project 1. Discussions with health authority decision makers produced a “short list” that was then ranked according to the most typical in the province based on key characteristics (e.g., size, operational model). The Saskatchewan modal LTC was a 100-bed facility, built in the 1950s, employing approximately 100 care staff and comprised two equal-sized units with central nursing stations and common areas.

Ethics and Consent Process

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Universities of Saskatchewan and Alberta. Operational approval was granted by the regional health authority, and consent was obtained from the facility board of directors. A letter describing the project was sent to the power of attorney of each resident, outlining a process of consent by exclusion and giving contact information for the researchers. Presentations were made at a resident council meeting and at three staff information sessions. Project brochures were distributed to staff and displayed in the facility.

Data Collection

This case study drew on the methods of both ethnography (data collection) and grounded theory (analysis). Case studies, which draw on a mix of sources, contribute to understanding of how to improve care and to developing theory on quality improvement in organizational research; qualitative data are most appropriate for case study research where theory is nascent and the research questions exploratory (Baker, 2011). Data were collected through observation, document review, and interviews. Between December 2008 and April 2009, a research associate conducted ethnographic observations (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 1995) recorded as fieldnotes to gain a full and rich description of the LTC context. Observations were conducted across all shifts and days of the week and focused on the general flow of events and operations in common areas of the facility. Neither personal care areas nor residents’ private rooms were observed. Staff and residents were advised that at any time during data collection they could ask to see the fieldnotes, which also included the research associate’s reflections on observations.

Although observations in the facility elucidated the daily work patterns that provide the context for knowledge use, specific observation opportunities included resident care conferences with family members and care providers, mealtimes, social activities, staff training sessions, and meetings. Documents such as policy manuals and a new resident care plan were collected and digitally scanned. Several staff were “shadowed” during their shift, which allowed for detailed exploration of work practices and use of knowledge in care provision, and provided the opportunity for informal discussions with care staff. Observational data collection ceased when the data categories were saturated.

Following the observational phase of data collection, fieldnotes were analyzed for common themes. The research team met to discuss these themes and to determine the interview strategy. Based on the fieldnote analysis, semistructured interview guides were developed for each of three staff categories: administrative, nurse/licenced practical nurse/allied provider, and care aide. A staff meeting was used to provide information about the interviews and invite participation. Theoretical sampling was used to identify key informants. Effort was made to ensure informants from each of the day, evening, and night shifts were interviewed. Prior to each interview, written informed consent was obtained. A copy of the consent was kept by the researcher and securely stored, and a copy was given to each participant. The process of digital recording was explained and participants informed that at any time they could turn off the recorder or ask that it be turned off. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Twenty-one in-depth, semistructured interviews were conducted with administrators (3), allied providers (2), registered nurses (3), licensed practical nurses (2), and care aides (11).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using constructivist grounded theory methods (Charmaz, 2006). Initial open coding was conducted, then more focused coding to develop thematic areas, then theoretical coding to develop an integrated model of how the LTC context influences knowledge use and best practice uptake. Team members met regularly to review initial codes, concepts, and thematic areas, and determine saturation of categories. Confirmability of thematic areas was attained by having multiple team members code data and compare theoretical analysis notes; the core category was developed through consultative theoretical analysis. Trustworthiness was promoted through the use of peer debriefing, theoretical memos, audit trail, prolonged engagement, and data triangulation (Shenton, 2004).

Findings

The key finding of this study was the high level of complexity of decision making with respect to resident care. This complexity is “hidden” because it is not immediately evident when entering the facility as a casual observer. The conceptual framework, The Hidden Complexity of Long-Term Care (Figure 1) depicts the features of organizational context that influence knowledge processes about caregiving, including use of best practice information. These factors are arranged from the most easily identifiable (physical environment) to the least visible or observable (philosophies). Six contextual categories are mediated by two facilitating features of the context. In the remainder of this section, we describe these concepts and their relationship to care practices.

Physical Environment

The physical environment is the most immediately identifiable factor of context. In this study, almost every aspect of a resident’s care was influenced by the environment, from the overall facility design and room layout to the location of storage and offices. Sometimes, care could not be accomplished in accordance with best practice guidelines because the environment did not allow it. For example, small bathrooms did not accommodate lift and transfer devices and were cramped when positioning devices were used. If a resident required a transfer device to use the toilet, a commode was used in the general area of their bedroom. The environment hampered the utility of devices intended to make care safer, and eroded staffs’ acceptance of technological advances in care. “You know how hard it is to manoeuvre with the big lift . . . it’s just because . . . this building is designed only for old people that [have] no frailties, no disabilities, but it turned out to be heavy care now” (Care Aide).

The placement and design of the nursing stations also created problems. The open design did not allow for private conversations about resident care, yet staff were unable to observe resident common areas or rooms while working at the stations because of the high counters. “See how the countertop comes up to her head? If you’re sitting at the desk you can’t even see any of the residents in small chairs. Just not appropriate” (Nurse). A lack of space was reported by all types of staff and frequently hindered care. For example, physical and occupational therapy staff were unable to do assessments when social activities were taking place in the common areas. Equipment and supply carts littered hallways, impeding the sight line of care staff and the walking path for residents. Carts obscured the hand rails, rendering this mobility aide useless. Thus, limitations in the physical environment necessitated modifications to care practices and prevented use of best practices.

Resources

Resources included physical resources (e.g., supplies, equipment, materials), human resources (e.g., specialists, staff), and intangible features (e.g., information, training, time). Access to needed resources enhanced best practice, whereas lack of resources impeded best practice. Equipment was a critical resource for providing care and as resident acuity increased, more specialized equipment was required. Lack of availability and poor state of repair of crucial equipment directly affected the quality of care and could contribute to resident and staff injury. Problems with the mechanized lifts and bathtubs were a constant source of stress. “I don’t know how many of our machines are broken. . . . you know that just today we couldn’t get a resident up because the lift wouldn’t put him in a sitting position for some reason. So we just laid him back in bed” (Care Aide).

Highly specific care devices such as airbeds and postural devices were in short supply with long waitlists and a time consuming, complicated process for access. For some items, cost was borne by the resident. If a waitlist was too long or a resident could not afford an item, staff were left to accommodate care as best they could. Information was a resource that influenced care. Information on operations, regulations, best practices, and resident needs was found in written form in policy and procedure manuals, medical charts, bulletin boards, and staff communication binders. However, information was most frequently sought informally, through conversation. In response to questions about where one would find information, a common answer was, “I would ask someone.”

Time was also a resource in short supply. Decisions were constantly made about what care to provide: “Well, sometimes you just have to do what you’re doing and deal with the situation a little later if it’s not pertinent. You kind of have to put your priorities where they belong. Like if it’s somebody that’s calling out for a glass of water . . . what’s more important, that or getting the medications out to your residents on time” (Nurse).

Staff reported that compared with even 5 years earlier, acuity of illness and care needs had increased substantially, but that staffing levels had not kept pace, “Well, the level of care is just so much more demanding. You see way more cognitive impairment. When people come to you if they’re not cognitively impaired they’re definitely more acutely ill” (Allied Provider). The fact that time was limited on a “normal” day was compounded by the fact that the facility was frequently short staffed. Nurses pointed out that within the acute care system, leaving a shift vacant was not a viable option, but within LTC it seemed a standard occurrence. Often this was because coverage was not available, but it was also described as a cost-savings measure. The impact of low staff–resident ratios and working short-staffed contributed to a sense of “anticipating” or waiting for the next difficulty. Staff demonstrated an adaptation of anticipation, guarding time through adherence to routines as a way of coping with this unpredictability, in an effort to control their workday.

Flux

The concept of “flux” encapsulates the multiple changes that constantly occurred within the LTC facility and the health region, over longer time periods, day-to-day operations, and moment-to-moment interaction with residents. The facility faced a number of large changes over the study period although staff did not perceive it as a time of major change. When asked about this, they responded that change was typical. Examples include a regionally centralized scheduling system, outbreaks of norovirus and influenza resulting in closure of the facility to nonstaff for an extended period, major renovation of a unit, the Administrator’s maternity leave, a 1-year temporary Care Coordinator with no background in LTC, a new Director of Care, new protocols to address infection control and regional pandemic planning, and a new region-wide resident care plan representing a macrolevel philosophical change in care.

Small, unpredictable, daily changes were a salient features of the LTC context. Routine was sought as a way to meet the needs of a large number of residents requiring numerous episodes of care and as a coping mechanism in response to the highly unpredictable nature of the context. At any time, unforeseen events could occur that required immediate attention such as a resident fall, equipment malfunction, staff injury, resident illness or death, or expression of dementia behaviors. Unpredictability meant that staff functioned in a constant state of adaptation or accommodation.

Communication was a key strategy to manage the impact of flux; without adequate communication, a change perceived as a minor disruption became unnecessarily stressful. The facility had many tools to facilitate communication about care practices and work flow including communication books, bulletin boards in each area, staff mailboxes, daily “report” meetings, biweekly staff meetings, monthly interdepartmental facility meetings, monthly resident council meetings, and weekly resident care conferences. Because changes occurred frequently over the course of each day, communication was critical within the LTC context.

A strong informal communication network functioned alongside the formal communication strategies. Full-time staff referred to “getting caught up” after days off and staff who worked part time seemed to be in a perpetual state of “catching up.” Maintaining awareness of the ongoing status of the residents was challenging, and reliance on standard ways of working was perhaps an attempt at continuity on some level. This was particularly important given the volume of unpredictable and ever-changing events that must be managed.

The need to cope with constant flux was an aspect of context that impeded planned change because it occupied staffs’ attention and thereby hindered the uptake and establishment of new care techniques and practices. Some staff seemed to handle the general state of flux effortlessly, without overt awareness that they were multitasking, whereas others demonstrated less ability to cope. Staff attributed this to personality or outside stressors that were impacting work, but mainly they attributed the skill to having tacit knowledge:

Aide: I don’t know, you just do. You do what you have to do. You just, I don’t know, like I said I don’t know how, I just do. [Interviewer: You just do?] Yeah. [Interviewer: Pretend I was trying to do your job. How would I get to that level?] Years of experience.

Additionally, the unpredictability of care and the in-the-moment responsiveness that it demanded was taxing and sometimes led to intransigency or defensiveness in other domains of work. Because of the lack of control over many aspects of the context, staff sought constancy in other areas of organization and sometimes reacted with distrust and scepticism when change was introduced. The Director of Care explained that a change in a product or modification of care is challenging to adopt, but that a philosophical change is much more difficult to achieve: “You don’t have to get people to buy in to a new cleanser the same way you have to get them to buy in to a different philosophy of care.”

Ambiguity

Few care practices within the LTC context were unambiguous or unaffected by other circumstances or factors. Some care decisions were complicated by lack of resources, creating a situation where the next best practices were debated and a course of action chosen. Competing health needs often complicated decision making. For example, a resident at risk for falls was considered a candidate for hip protector use, but this decision had to be weighed against reduced ability to toilet independently and increased risk of skin ulceration. Policies were sometimes contradictory, adding to ambiguity, such as the policy of nonrestraint, which contravened infection control isolation practices during outbreaks:

Well, we have a no restraint policy which means you can’t restrain residents – physically or chemically. So they continue to wander . . . It’s complicated, that’s for sure. We can’t control the wandering so we control the risk. We do a lot of redirecting, try to keep them from the main areas, from contact with other residents, we do a lot of hand hygiene and personal hygiene and we do a lot of surface cleaning. It’s a lot of work. . . . And then the illness itself takes its toll on the resident, they get ill and this increases the dementia behaviour – the dehydration from illness increases the confusion and the behaviour and it can become more difficult to mediate (sigh) and they’re more disoriented and at risk of falling while they wander . . . that is, until they’re so ill that they no longer wander or interact . . . and then that’s scary too. But that’s the reality of LTC. (Administrator)

What was taught as a gold standard approach was not always achievable within the LTC context, leading to confusion. Adapting best practices to match resources or system allowances can dilute the use of evidence. Conflicting recommendations among specialists weakened trust in those authorities, making their jobs more difficult when trying to implement care-enhancing practices and complicating their role as trusted “expert.” Thus, ambiguity eroded confidence in teachings of best practice.

Relationships

Relationships existed among different levels of workers, among residents, between residents and staff, between family and residents, and between family and staff. Relating to others was an integral aspect of context affecting how care was provided and knowledge applied. Relationships between providers and residents were pivotal given the nature of personal care provision. Staff described their “personal approach,” the way that they related to each resident, and the relationship shared between themselves and residents, as key features of quality care. “Oh I love the people. I love the clients. I love this age group of people. . . . I mean it’s very rewarding. I mean you have to keep it all in context. You have tasks to do but you can make a difference in their lives. It keeps you coming back to the job” (Care Aide).

Working in close quarters and giving care that is often physically, mentally, or emotionally challenging can be made better or worse depending on relationships with coworkers. Attitudes and personalities of coworkers were cited by staff as affecting their satisfaction with work and ability to adopt a care practice. Staff contextualized relationships as helping to transcend other challenges such as working short staffed.

I’ll tell you something about this job, this job is about resident care and the other part of the job is about getting along with people and I believe strongly and firmly about that. It’s about getting along with your coworkers, other departments, your supervisors, management, families, you know visitors, everybody, the delivery guy, everybody and, um, like it’s really a requirement to the job . . . (Care Aide)

Relating to residents, family members, other staff, and the myriad visitors, volunteers and specialists were a central feature of working in the facility. Relationships were pervasive; all aspects of care provision involved a relational component. As such, the status of relationships played a critical role in the general tone of the facility and the overall context of caregiving. Healthy supportive relationships that fostered trust and cooperation allowed staff to try new ideas and put new concepts into practice.

Philosophies

Within the facility, several philosophies operated simultaneously: the formally adopted mission/vision/values of the region and the organization, the facility’s philosophy of care, the personal philosophies and beliefs that care providers brought with them to their work, and the staff’s entrenched mindsets. These multiple philosophies established the unique culture of the organization and influenced care provision. General operations, daily flow, and customs were aspects of context that staff learned through experience. Much of the training for new staff focused on explaining processes and “indoctrinating” the new person. Staff learned how to “fit in” and interact within the culture to gain acceptance. This “cultural assimilation” was not limited solely to training new staff; knowledge transfer and adoption of new practices also followed this process. Whether a practice was embraced and integrated depended in large part on its fit with the current culture of the health system as a whole and the facility as a part of that system.

Often certain philosophies directly contradicted one another or had conflicting aspects. This discord was most obvious in terms of the conflict between “homelike” and “institution.” A guiding principle of the LTC facility was to be homelike. Efforts were made to respect the philosophy of “home,” but the best that could be expected was an approximation because there was no avoidance of the fact that this was also an institution. Workplace guidelines, policies, routines, and legislation such as occupational health and safety codes dictated daily operations as much as the philosophy of “homelike.”

Experience and Confidence

Features of knowing LTC practices and the milieu, the resident, the region, and the facility were key to having confidence to provide care effectively and efficiently. The contrast between care providers with and without experience illuminated this feature of knowledge use: when preoccupied with the general background features of the LTC workday, less-experienced care providers had far greater difficulty considering best practice evidence, troubleshooting, or determining the best care approach. Experienced care providers showed confidence in quickly weighing evidence from multiple sources and making complicated decisions in a manner that appeared effortless, whereas less-experienced providers were typically more routine based and task focused, exhibited less flexibility in their role, contributed less to decision making, and were less independent. Many described a steep learning curve in gaining an understanding of the organization, general care procedures, evolving needs of individual residents, and the role that their particular job fulfilled within this mix. Staff explained that knowledge about care could be gained through education, in-services, and information sources, but that the component critical to putting that knowledge into use was experience. “You have to really experience, well you can read from the books when you’re in school. They’ll probably give you tips on what to do, but I think you have to really experience . . . like, hands-on” (Care Aide).

The source of experience mentioned most often by care providers was personal knowledge of individual residents. Without this, care provision was slowed and could not be adequately tailored. Knowing the resident’s unique concerns and preferences allowed care providers to identify the most appropriate care strategies. Not knowing the resident created hesitancy and uncertainty. Staff were clear that this knowledge was not limited to the residents’ health; their personality and past life experiences were sources of information that contributed to staffs’ confidence in providing care to residents.

. . . there was one lady and every time we went to put her in the bathtub she would just like LOSE it totally, even with medication onboard she still – and then one of her family members came in one day and was telling us that when she was younger her two older brothers held her down in a trough or whatever and like that all I guess came back to her every time she went down in the lift into the water. So then that made it a little bit easier to know that’s why she is the way she is and maybe we can work that a bit more and take the little bit of extra time to explain things what we’re doing. (Nurse)

Experience could have a negative impact, typically when an experienced staff member became frustrated with a newer staff member due to the amount of time that person was spending performing care. Though the new aides were performing resident-centered care, the more experienced worker knew that the context did not allow for that type of attention; another resident would be short-changed or a backlog of work would be created. Some experienced staff became complacent to the compromises made in the standard of care.

One thing that really bugged me at first was that they couldn’t toilet people when they requested that sometimes it was mealtime and they’d say you have to wait . . . and you know that bothered me. So I have gotten jaded that way. I’ve learned that there just isn’t time. (Nurse)

Experienced staff were much more able to multitask, make competent decisions, and work more efficiently. Those with more confidence could better negotiate the complexity of decision making within ambiguous situations and manage resources efficiently. In this way, experience and confidence mediated other features of the LTC context.

Leadership and Mentoring

Particular care providers played key roles in setting a tone, acting as a role model, mentoring, transforming mistakes into learning opportunities, or sharing key examples. Leaders were of two types: formal leaders who occupied positions of authority and informal leaders who had no formal assigned role as a leader or supervisor, but functioned as a key mentor, guiding and shaping the flow of daily care, and troubleshooting when necessary. Positive aspects of leadership included empowering others, sharing information and knowledge, encouraging independence, sharing power, and fostering good relationships. Leadership was seen as a continuous task that permeated care. Leaders decided how and where to focus attention and resources, and balanced the many interrelated issues faced within LTC.

The significance of leadership was evident when examining staff reaction to change in the style of leadership. The formal leaders within the facility had changed prior to the project beginning, from a more authoritarian style to a more cooperative style, pursuing a more “flat” organizational chart. Though the majority of staff expressed satisfaction with the changes, some displayed hesitancy in adapting to the new style by continuing to ask permission for minor changes or consulting with formal leaders over small matters. Formal leaders mentored decision making by redirecting questions and allowing the care staff to come up with the best solution. Nurses worked to empower care aides, helping them build confidence in discussing care issues with families or physicians, for example. “[Confidence is] a big thing. It’s huge and you really need it. You need it to do this job . . . . you really do need to feel confident because actually the residents will pick up on it too” (Care Aide).

Confident informal leaders mentored others by transforming mistakes into learning opportunities, often poking fun at themselves to emphasize that all staff can and will make errors, and that open discussion is the only way to correct and prevent reoccurrence. An example of this occurred when a new care aide found a small object in a resident’s mouth when assisting with feeding. She brought it to the nurse who then identified it as a piece of a crushed pill. In response to this, the nurse gathered all care staff and showed them the pill fragment explaining that this was exactly the type of thing that they should bring forward, and reaffirmed that a dangerous error could go unnoticed if the aide had not been diligent in her attention. Leadership and mentoring mediated the influence of other aspects of the LTC context, supporting staff in navigating the system and making care decisions. Principles of care modeled by strong leaders help to entrench best care practice.

Summary of Findings

Care is often viewed as an act between a care provider and a resident, but it is important to not overlook the context shaping those acts. As our model shows, context is often obscured or hidden when considering how knowledge and best practices are incorporated into care. This model of context illustrates the facets of LTC context that influence use of knowledge and best practice use. The categories interrelate to form a picture of context not immediately recognized on first appraisal of the LTC. As the figure illustrates, the categories physical environment and resources are most easily discernible as to their impact on knowledge use and resident care. Flux and ambiguity are less tangible and play a more intermediate role in influencing care practice, whereas relationships and philosophies function as contextual drivers of knowledge use and care. The categories experience & confidence and leadership & mentoring are features of the LTC context serving to mediate and bridge features of the other categories.

Discussion

The emergent model of The Hidden Complexity of Long-Term Care highlights the challenging nature of providing care in LTC settings, as a result of the numerous interacting and continually evolving contextual factors that influence care. Beyond the physical environment and resources such as equipment, these factors are not immediately evident, thus disguising the complexity of caregiving in the LTC context. Dopson (2007) presented several dimensions of organizational complexity relevant to knowledge translation research that are consistent with the findings of our study. These include the contestability of the evidence base for many health care innovations, conceptualization of local contexts as multidimensional configurations of forces that interact in complex ways, and acknowledgment of context as playing an active role in knowledge translation rather than simply a backdrop (Dopson, 2007).

Some contextual factors influencing the implementation of evidence into practice identified in this study have been identified in other health care settings, including resources (McCormack, 2001; Rycroft-Malone, 2008) and leadership (Rycroft-Malone, 2008). The concepts of flux (leading to unpredictability and uncertainty) and competing philosophies identified in this study have parallels in earlier dementia-care studies. Janes and colleagues (2008) developed the theory “Figuring it Out in the Moment” to describe the process by which care aides in dementia units made decisions about and acted on knowledge related to person-centered care. The aides’ decision-making process “involved a complex myriad of interrelationships” among contextual, individual, and relational factors. These include uncertainties inherent in dementia care (related to residents’ changing mood, behaviors, and response to caregiving) and the influence of care aides’ relationships with others on capacity to provide person-centered care (p. 15). The link between knowledge utilization and contextual factors of unpredictability and the primacy of social relations (teamwork, inclusion, and recognition) were also found in our current study.

A second study of personal support workers’ point-of-care decisions (Kontos, Miller, Mitchell, & Cott, 2010) also highlighted the complexity of decision making. Kontos and colleagues (2010) examined the causal mechanisms between human agency (the capacity of an individual to act independently and exercise choice) and structure (e.g., norms, institutions). Their findings demonstrated the contingent nature of decision making in LTC and pointed to the complexity of care dynamics in which standards of care and institutional policies influenced day-to-day organizational care delivery. Care decisions resulted from staff’s internal conversations as they processed discordance between standards and rules and their personal beliefs about individualized care needs of residents. Kontos and colleagues (2010) recommend extending this exploration of care aide work to understand other factors that might influence their decision making and ultimately the quality of care provided. Our findings point to the importance of examining context as a feature in all care decisions. Care is often viewed as a discrete act between care provider and resident, but our study demonstrates that it is crucial to understand the interplay of contextual factors as a determinant of how care is executed.

The majority of care in LTC settings is provided by care aides, who have the least amount of formal training. Our study and others that have examined aides’ decision-making processes and the factors that constrain and enable the actions of care aides, underscore the challenging nature of care provision in LTC. Care aides are expected to provide person-centered care to residents with increasingly complex care needs, in an environment that is often short of resources, unpredictable, and unclear about the best course of action. We found that staff tended to rely on organizational routines as way to manage workload and the unpredictable nature of the LTC context, sometimes at the expense of resident-centered care provision. The need to cope with the constant flux operating in the background interfered with planned change because staff were preoccupied. Fatigue resulting from working short-staffed, responding to unpredictable resident behaviors, and the constantly changing work context also contributed to staff being less receptive to efforts to implement new practices. By better understanding this complexity, it will be possible to modify those aspects of context that impede use of best practices and develop effective knowledge translation approaches that support staff in providing the highest quality of care.

Meijers and colleagues (2006) used the PARIHS framework to examine research use in nursing practice, and found that measurement of context is challenging due to the complex and multifaceted nature of care work, which resonates with our findings. Berta and colleagues (2010) note that consideration of organizational context will be key to policy efforts that support evidence-based practice in LTC. Hirdes, Mitchell, Maxwell, and White (2011, p. 15) argue that the future of LTC will include “a more clinically complex population with substantially greater needs for care.” Care provision will become increasingly complex, dictating the need for better training of care providers and application of innovations in care practices. Greenlaugh, Robert, MacFarlane, Bate, and Kyriakidou (2004, p. 615) note that research on health service innovation should focus on process and “recognize the reciprocal interaction between the program that is the explicit focus of research and the wider setting in which it takes place.” As Dopson (2007) states, “there is a need for finely-grained and holistic analyses of the processes of knowledge translation within real-life clinical settings” and longitudinal studies that track the career of the innovation over time. Our study was an initial broad overview of context in a LTC setting that identified eight interrelated dimensions of context that influence use of knowledge in LTC. Future research is needed that explores these factors in-depth, and in relation to specific knowledge translation innovations in LTC settings.

Study Limitations and Strengths

The study facility was selected as a typical LTC facility for a particular geographic area, therefore transferability may be limited to those with similar characteristics. Although we have an understanding of contextual factors that mediate knowledge use in this facility, further work is needed to establish the transferability of findings. Strengths of the study include triangulation of data from multiple sources, interviews with all categories of care staff and management, and prolonged engagement at the study site for more than 10 months.

Conclusion

This study illustrates the hidden complexity of the LTC context that each individual care provider must negotiate. LTC contextual complexity is not apparent on initial examination; decisions regarding care provision are imbued with nuance, largely due to interconnected contextual influences. The model developed in this study demonstrates key factors that operate within the context of LTC that should be considered when assessing care provision and best practice. Navigating challenges of inappropriate physical environment, inadequate resources, ambiguous situations, continual change, multiple relationships, and often contradictory philosophies makes for an extremely complicated context in which to provide care. This complexity is mediated through tacit knowledge and development of confidence and through empowering leadership and supportive mentoring. Attending to the complexity of the context in which care decisions are made will lead to improvements in knowledge exchange mechanisms and best practice uptake in LTC settings.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP 53107).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the facility and staff who participated in this project.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Nancy Schoenberg, PhD