-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

S.A. Magrys, M.C. Olmstead, Acute Stress Increases Voluntary Consumption of Alcohol in Undergraduates, Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 50, Issue 2, March/April 2015, Pages 213–218, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu101

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Aims: The primary aim of this study was to assess whether an acute stressor directly increases alcohol intake among undergraduates. A secondary aim was to examine whether individual differences in state anxiety predict alcohol intake. Method: Following random assignment, undergraduate students (n = 75; 47% males; mean age = 20.1 ± 2.8) completed the Trier Social Stress Test or no-stress protocol, and then engaged in a 30-min free-drinking session (alcohol, placebo, or non-alcoholic beverage). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was completed upon arrival, post-stressor, and after drinking. Results: Planned comparisons demonstrated that psychosocial stress increased voluntary intake of alcohol, but not placebo or non-alcoholic beverages. In linear regression analyses, individual differences in anxiety did not predict voluntary alcohol consumption. Conclusion: A proximal relationship exists between acute stress and single-session alcohol intake in undergraduates, which may explain the relationship between life stressors and increased drinking in this group. These findings demonstrate that stress management is an important target for reducing heavy episodic drinking on university campuses.

INTRODUCTION

Risky drinking is a significant problem among undergraduate students, many of whom exhibit high rates of alcohol consumption (Balodis et al., 2009). Heavy drinking in this group is not only associated with social, academic and health problems (Wechsler and Nelson, 2001), but also significantly predicts later development of alcoholism (O'Neill et al., 2001). Thus, factors that contribute to excessive consumption of alcohol during college and university may indirectly confer risk for later alcohol abuse. Stress is one of the most likely contributing factors in that stressful life events are associated with elevated alcohol use, as well as increased likelihood of alcohol abuse (Enoch, 2011; Boden et al., 2014). Moreover, students studying in higher education institutions experience elevated levels of stress related to new time demands, greater workload, financial strain and examinations (Robotham and Julian, 2006). As with other populations, university students report increased alcohol consumption during periods of increased life stress (Park et al., 2004).

Given the relationship between life stressors and alcohol use, it seems plausible that acute stress directly increases alcohol consumption. Human studies addressing this hypothesis, however, have produced mixed results. Early findings showed that exposure to an acute stressor increases alcohol intake (Hull and Young, 1983), although more recent research suggests that the effect is no greater than a placebo control, at least in healthy social drinkers (de Wit et al., 2003). It is possible that the stress-alcohol association may be limited to, or at least more pronounced in, pathological populations. This appears to be the case with high anxiety, as alcohol use disorders are highly comorbid with anxiety disorders (Grant et al., 2004), and the association between stress and drinking is particularly strong in these groups (Waldrop et al., 2007). The co-occurrence of anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders may reflect the fact that individuals with pathological anxiety are motivated to ‘self-medicate’ by drinking (Khantzian, 1997). These findings fit with preclinical studies showing that pharmacological blockade of stress systems decreases excessive intake of alcohol to a greater extent in dependent, versus non-dependent, rats (see Silberman et al., 2009; Mahoney and Olmstead, 2013). It should not be surprising, therefore, that much of the research examining stress effects on voluntary alcohol intake has focused on populations with substance abuse and/or anxiety disorders. For example, stress-induced increases in voluntary alcohol intake are seen in social phobia (Abrams et al., 2002) and among individuals at risk for alcohol use disorders, such as those with a positive family history of alcoholism (Soderpalm Gordh et al., 2011).

In contrast to this work with clinical populations, the relationship between acute stress and alcohol consumption in healthy individuals is not well understood. The relationship may be explained by individual differences in anxiety, given that everyday alcohol consumption in non-pathological populations depends on an individual's perceived level of stress (Park et al., 2004). Moreover, both normal drinkers and alcoholics commonly endorse using alcohol for the express purpose of reducing anxiety (Boys et al., 2001; Robinson et al., 2009). Taken together, these data highlight the subjective nature of perceived stress and suggest that some individuals consume alcohol to directly manage dynamic states of subjective anxiety. Thus, state anxiety may be an important direct predictor of voluntary alcohol intake, irrespective of exposure to acute stress. This is particularly relevant to undergraduate populations who face a variety of dynamic stressors, some of which may be transient in nature (Robotham and Julian, 2006).

The primary purpose of the current study was to examine whether acute stress increases alcohol consumption in an undergraduate population. In order to control for the effects of alcohol expectancies, both placebo and sober control groups were included. Another aim of this experiment was to examine whether individual differences in state anxiety predict single-session alcohol intake.

METHODS

Participants

The protocol for the current study was approved by Queen's University Graduate Research Ethics Board. Seventy-five undergraduate students (35 men and 40 women) were recruited using the subject pool from an introductory undergraduate psychology course, as well as print advertisements on campus. To be eligible for participation, students were required to be at least 19 years of age (the legal drinking age in Ontario) and report drinking alcohol at least once per month. Exclusion criteria included previous medical history contraindicating the use of alcohol, allergy to alcohol and/or use of medication that may interact with the effects of alcohol. These inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed using a screening questionnaire that was completed before individuals arrived at the laboratory. Due to the deleterious effects of alcohol use during pregnancy, females were only permitted to participate on the day of testing if they were menstruating, or had not had sexual intercourse since their last menstruation. Prior to the beginning of experimental procedures, participants were randomly assigned to one of three drinking conditions: alcohol (n = 24), placebo (n = 26) or sober (n = 25). Within each of these groups, participants were assigned to a stress (n = 24) or no-stress (n = 51) condition. The discrepancy in size between these two groups is owing to the fact that the stress manipulation requires additional personnel and laboratory resources, restricting the rate at which participants were run in this condition over time.

Self-report measures

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a questionnaire that measures feelings associated with anxiety, such as tension, apprehension, nervousness and worry (Spielberger, 1983). The STAI includes two subscales, the STAI-Trait (STAIT) that measures trait anxiety (long-standing individual quality), and the STAI-State (STAIS) that measures state anxiety (temporary status associated with reactivity to acute stressors). Each subscale is comprised of 20 items and provides a rating from 20 to 80, with higher scores relating to greater anxiety.

Perceived intoxication

A modified version of the Drug Effects Questionnaire (de Wit et al., 2003; Ortner et al., 2003) was used to assess subjective feelings associated with intoxication. This brief self-report questionnaire asked participants to estimate how much alcohol they consumed, their blood alcohol level, as well as rate how intoxicated they feel, how much they enjoy how they feel, and the extent to which they want more alcohol. It served as a manipulation check to assess subjective intoxication and the effectiveness of the placebo condition.

Stress condition

For individuals assigned to the stress condition, the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) was used to induce a stress response (Kirschbaum et al., 1993). The TSST is a psychosocial stressor that capitalizes on highly stressful factors including uncontrollability, forced failure, and social-evaluative threat. The procedure reliably elicits elevations in stress measures in healthy normal populations (Kudielka et al., 2007) including a robust hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis response with a long recovery time (Kirschbaum et al., 1993).

This task involved performing a 5-min speech in front of a panel of student actors, followed by a 5-min mental arithmetic task. The TSST was conducted in a separate room, where there were two student-actors who were introduced to the participant as a doctoral student in linguistics specializing in non-verbal behaviour, and a professor in the Psychology department. The participant was asked to give a mock job talk for a position as a research assistant in the Psychology department, then was given a pen and paper and allowed 5 min to prepare. When the preparation time had expired, any notes the participant had made were taken away and the individual was told that their performance would be compared against their written information. The participant was able to see his or her image on the LED screen of a camcorder during their performance.

Participants assigned to the no-stress condition were brought into a separate room, where they sat quietly and completed simple crossword puzzles, in order to provide some cognitive stimulation, for the same amount of time as the stress protocol.

Drinking protocol

Participants were requested to fast for 3 h prior to testing in order to minimize variability in the rate of alcohol absorption. A modified version of a validated ad libitum drinking protocol was employed (de Wit et al., 2003) in which participants were instructed to consume an initial drink of their beverage (alcohol, placebo, or non-alcoholic), and were then permitted to continue consuming the beverage ad libitum for the next half hour, up to a maximum of six drinks. For the alcohol group, the initial drink contained 0.2 g/kg alcohol for females and 0.3 g/kg alcohol for males; subsequent beverages contained 0.1 g/kg alcohol for both sexes. The alcoholic beverages were comprised of two parts calorie-free soda to one part vodka. Placebo beverages contained flattened tonic water instead of alcohol and, to mimic smell and taste cues, a small amount of alcohol was placed on the rim of the glass and floated on top of the beverage. In the sober condition, participants received a non-alcoholic beverage (calorie-free soda). For both the placebo and alcohol groups, participants were told they were receiving moderate-dose alcoholic beverages, whereas participants in the sober group were told they were receiving non-alcoholic beverages.

In order to maintain ecological validity, all participants completed the drinking protocol in a laboratory setting that simulated a comfortable living room environment while watching DVDs of a popular TV show. Consistently, participants always completed the free-drinking portion with one or more other individuals, as drinking alone occurs rarely (∼15%) among university students (O'Hare, 1990). Participants and, when necessary, confederates completed the protocol in a staggered fashion in order to allow individuals to drink together without participants knowing how much alcohol the other individual had consumed. If only one individual participated in a given testing block, a student-actor served as a confederate, posing as another participant, during the free-drinking portion.

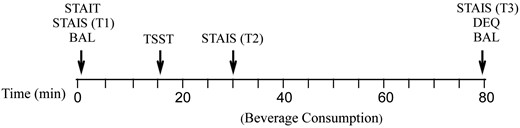

Experimental procedure

After arriving in the laboratory, participants underwent a final screening for eligibility and provided written consent. Participants were weighed for beverage dosage, and an initial blood alcohol level (BAL) reading was taken using a breathalyser (Intoxilyzer 400D; CMI, Inc., Owensboro, KY, USA). Participants first completed a set of self-report questionnaires, the STAIT and STAIS (T1), before going to a separate room to undergo the stress or no-stress protocol depending on their group assignment. Participants then returned to the laboratory and completed the STAIS again (T2). They were then told whether their beverage was alcoholic or non-alcoholic, and began the drinking protocol. After the free-drinking period, participants completed the modified Drug Effects Questionnaire as a manipulation check as well as the final STAIS (T3), and provided another BAL reading. A brief behavioural measure was completed as part of a separate study, before participants were debriefed and compensated with course credit through the psychology subject pool or with cash remuneration ($10). Participants in the alcohol group stayed in the laboratory until their BAL was below 0.06% and were provided with a taxi ride home. The procedural timeline is depicted in Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of experimental timeline. STAIT, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait; STAIS, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—State; BAL, blood alcohol level; TSST, Trier Social Stress Test; DEQ, Drug Effects Questionnaire; T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2; T3, Time 3.

RESULTS

Participants

Participants were between 19 and 36 years old with a mean age of 20.12 years (SD = 2.81). They reported drinking an average of 1.69 times per week (SD = 0.85). The proportion of males versus females did not differ by beverage group, χ2(2, n = 75) = 0.89, P = 0.51, or stress condition (P = 0.81). Average weight (kg) did not differ between the three beverage groups, F(2, 74) = 2.01, P = 0.14.

Manipulation checks

Stress

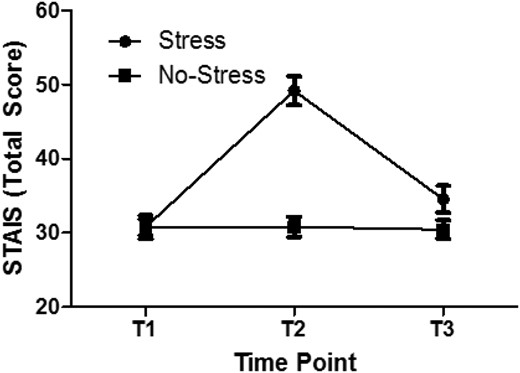

A 2 × 3 repeated measures ANOVA (see Fig. 2), with stress condition as the between-subjects variable and time as the within-subjects variable revealed a main effect of stress, F(1, 73) = 16.85, P < 0.001, and a main effect of time, F(2, 133.02) = 45.52, P < 0.001 (Huynh-Feldt corrected) on STAIS scores. Following a significant stress × time interaction, F(2, 146) = 43.76, P < 0.001, simple effects analyses with Bonferroni correction (alpha = 0.008) showed the effect of time occurred only within the stress group, F(2, 72) = 48.75, P < 0.001, wherein scores at T2 were significantly higher than at T1 and T3, and scores at T3 were significantly higher than at T1, all P < 0.008. The effect of stress only emerged at T2, F(1, 73) = 59.59, P < 0.001, in that the stress group reported higher STAIS scores than the no-stress group, P < 0.008.

Effect of stress on state anxiety across experimental time points. STAIS, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—State; T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2; T3, Time 3.

Perceived intoxication

Table 1 shows BAL and self-reports of perceived intoxication levels in the placebo and alcohol groups. The sober group is not included in this table because they did not receive alcohol and did not provide reports of perceived intoxication.

Mean (SEM) blood alcohol level (BAL) and self-reported perceived intoxication in placebo and alcohol groups

| Beverage group . | BAL . | Perceived intoxication . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated alcohol consumed . | Estimated intoxication level . | Estimated BAL . | Liking the effects . | Desiring more alcohol . | ||

| Placebo | 0.00 (0.00) | 3.38 (0.30) | 2.87 (0.20) | 0.07 (0.05) | 6.28 (0.29) | 5.24 (0.52) |

| Alcohol | 0.04 (0.01) | 4.71 (0.36) | 3.96 (0.29) | 0.11 (0.03) | 6.54 (0.29) | 5.54 (0.50) |

| Beverage group . | BAL . | Perceived intoxication . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated alcohol consumed . | Estimated intoxication level . | Estimated BAL . | Liking the effects . | Desiring more alcohol . | ||

| Placebo | 0.00 (0.00) | 3.38 (0.30) | 2.87 (0.20) | 0.07 (0.05) | 6.28 (0.29) | 5.24 (0.52) |

| Alcohol | 0.04 (0.01) | 4.71 (0.36) | 3.96 (0.29) | 0.11 (0.03) | 6.54 (0.29) | 5.54 (0.50) |

Participants estimated the amount of alcohol they had consumed in terms of number of standard drinks (bottles of beer), level of intoxication, and BAL. In addition, they rated how much they liked the effects they felt, and how much they desired more alcohol. (All scales 1–9, except BAL [exact value].)

Mean (SEM) blood alcohol level (BAL) and self-reported perceived intoxication in placebo and alcohol groups

| Beverage group . | BAL . | Perceived intoxication . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated alcohol consumed . | Estimated intoxication level . | Estimated BAL . | Liking the effects . | Desiring more alcohol . | ||

| Placebo | 0.00 (0.00) | 3.38 (0.30) | 2.87 (0.20) | 0.07 (0.05) | 6.28 (0.29) | 5.24 (0.52) |

| Alcohol | 0.04 (0.01) | 4.71 (0.36) | 3.96 (0.29) | 0.11 (0.03) | 6.54 (0.29) | 5.54 (0.50) |

| Beverage group . | BAL . | Perceived intoxication . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated alcohol consumed . | Estimated intoxication level . | Estimated BAL . | Liking the effects . | Desiring more alcohol . | ||

| Placebo | 0.00 (0.00) | 3.38 (0.30) | 2.87 (0.20) | 0.07 (0.05) | 6.28 (0.29) | 5.24 (0.52) |

| Alcohol | 0.04 (0.01) | 4.71 (0.36) | 3.96 (0.29) | 0.11 (0.03) | 6.54 (0.29) | 5.54 (0.50) |

Participants estimated the amount of alcohol they had consumed in terms of number of standard drinks (bottles of beer), level of intoxication, and BAL. In addition, they rated how much they liked the effects they felt, and how much they desired more alcohol. (All scales 1–9, except BAL [exact value].)

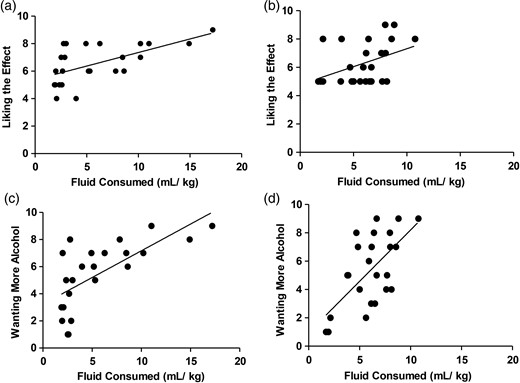

Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between fluid intake and manipulation check items in the alcohol and placebo groups. Within the alcohol group, fluid consumption per body weight (ml/kg) was significantly positively correlated with liking the effects of alcohol, r = 0.60, P < 0.01, and wanting more alcohol, r = 0.70, P < 0.01, but was not correlated with estimations of intoxication, all P-values > 0.05. The same pattern emerged in the placebo group, in that fluid consumption by weight was significantly positively correlated with liking the effects of alcohol, r = 0.41, P < 0.05, and wanting more alcohol, r = 0.62, P < 0.01, but not with estimations of intoxication, all P-values >0.05. These relationships are shown in Fig. 3.

Relationship between manipulation check items and fluid intake. The top scatter plots show correlations between fluid intake (ml/kg) and liking the effects of the beverage (scale 1–9) in the alcohol (a) and placebo (b) groups; the bottom scatter plots show correlations between fluid intake (ml/kg) and wanting more beverage (scale 1–9) in the alcohol (c) and placebo (d) groups.

Effect of stress on fluid intake

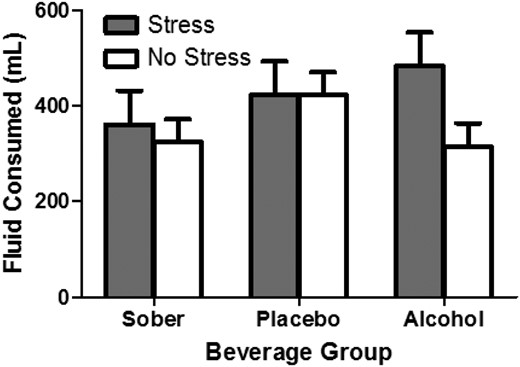

Planned comparisons were conducted to test the specific a priori hypothesis that participants would consume more fluid in the stress condition compared with the no-stress condition, but only in the alcohol group. Comparisons using orthogonal weighted contrasts to compare the stress and no-stress groups were conducted at each level of the beverage group variable. Given a priori predictions about directionality of the effect—mean fluid consumption will be higher for the stress condition compared with the no-stress condition—the tests were one-tailed. The contrast analyses demonstrated that there was no significant difference in mean fluid consumed between the stress and no-stress conditions in the sober (Contrast Estimate [CE] = 37.72, SE = 85.48), P = 0.66, or placebo (CE = −0.78, SE = 84.72), P = 0.99, groups. In contrast, within the alcohol group (CE = 169.06, SE = 86.33), mean fluid consumption was significantly higher in the stress condition compared with the no-stress condition, P < 0.05. These results are summarized in Fig. 4.

Effect of stress and beverage group on fluid intake. Bars represent mean (+SEM) fluid intake (total ml) for participants in sober, placebo and alcohol groups in the stress and no-stress conditions.

Relationship between self-report anxiety measures and alcohol intake

Nonparametric linear regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between alcohol intake and self-report anxiety measures within the alcohol group.

Trait anxiety (STAIT scores) did not significantly predict alcohol intake (ml), β = −0.05, t(22) = −0.25, P = 0.81. State anxiety, (STAIS scores) did not significantly predict alcohol intake (ml) at T1, β = −0.14, t(22) = −0.25, P = 0.51, or T2, β = 0.04, t(22) = 0.20, P = 0.84.

DISCUSSION

A primary finding of our study was that acute stress selectively increases voluntary intake of alcohol. Earlier work demonstrated that alcohol intake increases following exposure to an acute stressor (e.g. Higgins and Marlatt, 1975), a finding that was replicated in subsequent work (e.g. Pelham et al., 1997; de Wit et al., 2003; Nesic and Duka, 2006; Soderpalm Gordh et al., 2011). Nonetheless, these results are difficult to interpret without sober and placebo control groups. For example, the inclusion of a placebo control group showed that intake of both alcohol and placebo beverages increases post-stressor (e.g. de Wit et al., 2003). Thus, it is not clear whether the effect of stress is specific to alcohol drinking, or non-specifically related to factors such as thirst. We examined this possibility by including both sober and placebo control groups in our experimental design, revealing that acute stress specifically increases the intake of alcohol. As such, our data present the first evidence, in humans, that stress-induced alcohol consumption is related to the pharmacological effect of alcohol. This finding does not support a role for the expectancy of intoxication or other factors, such as thirst, in increased drinking following a stressor. The discrepancy between our results and findings of non-specific increases in both alcohol and placebo consumption following stress may also relate to other methodological differences. For example, previous studies have employed mixed between- and within-subjects designs (e.g. de Wit et al., 2003), in which a significant change between stress and no-stress conditions is determined, at least in part, on an individual level. The fact that stress increased beverage consumption, selectively, in the alcohol group relates to the theory that small amounts of alcohol prime individuals to seek more of the drug (Field et al., 2010). This may occur through an interaction with cognitive mechanisms controlling impulsivity in that a moderate dose of alcohol impairs inhibitory control, which in turn significantly predicts ad lib intake of alcohol (Weafer and Fillmore, 2008). The finding that this effect is more pronounced in the stress condition may be related to the fact that stress and impulsivity interact to increase alcohol consumption (Hamilton et al., 2013) and alcohol-related problems (Fox et al., 2010) in normal healthy drinkers. This possibility could be addressed in future research examining how trait or behavioural impulsivity moderates the relationship between acute stress and ad lib alcohol consumption.

Despite our finding that acute stress increases alcohol intake, our data did not support the notion that individual differences in anxiety relate to voluntary alcohol consumption. According to self-medication theories, individuals drink to alleviate anxiety but participants in our study who reported greater subjective anxiety, both upon arrival in the laboratory and prior to drinking, did not consume more alcohol. Similarly, trait anxiety did not predict alcohol consumption. Moreover, acute stress did not increase intake of the placebo beverage, again contradicting self-medication hypotheses in that the expectancy of alcohol (and the subsequent alleviation of anxiety) should motivate alcohol drinking. The lack of a relationship between state anxiety and alcohol intake in normal, healthy undergraduates may lend support to the notion that this association is limited to pathological populations. However, it could be that healthy normal participants exhibit insufficient dynamic range in measures of anxiety to produce the robust effects on alcohol consumption seen with pathological populations. Alternatively, it may be the case that individual differences in other factors, such as anxiety sensitivity, contribute to the relationship between subjective anxiety and alcohol intake and this should be explored, further, in non-pathological populations.

Replicating previous studies, our placebo manipulation was robustly effective in terms of perceived intoxication (Balodis et al., 2011; Christiansen et al., 2013; Magrys et al., 2013) in that the placebo group's estimated BAL did not differ significantly from that of the alcohol group. In terms of the positive subjective effects of alcohol, the placebo and alcohol groups demonstrated the same pattern: greater volume of beverage intake was significantly positively correlated with liking the effects and wanting more. To our knowledge, this dose-dependent placebo effect, relating beverage intake to the expected, positive subjective effects of alcohol, is a novel finding. In contrast, neither the alcohol nor the placebo groups showed a significant relationship between alcohol intake and any measures of estimated intoxication. In other words, intoxicated individuals were no better than participants in the placebo group at estimating their level of intoxication relative to the amount of beverage they had consumed. Thus, perceived levels of intoxication do not appear to be aided by physiological cues related to the pharmacological effects of alcohol, at least in this population.

In sum, our study provides evidence for a proximal relationship between acute stress and single-session alcohol intake, but does not support state anxiety as a significant predictor of this behaviour. Past research has examined whether acute stressors directly increase voluntary consumption of alcohol; our study clarifies this relationship by accounting for expectancy and general stress effects through the use of placebo and sober controls, respectively.

Potential limitations of the current study, and directions for future research, should be noted. It is possible that our study, given its relatively small number of participants, may have failed to detect subtle patterns in the data. Future experiments involving a greater number of participants would help clarify whether additional results, such as placebo- or dose-related effects, would be detected with greater statistical power. Although efforts were made to simulate a normative drinking environment for undergraduates (living room setting, evening time, in the presence of peers), the generalizability of these findings may have been limited by certain factors that do not reflect typical drinking circumstances, such as the duration of the free-drinking period of ∼30 min. Some studies have begun to examine ad lib drinking in naturalistic settings (e.g. Bot et al., 2005) and this approach would be useful in further exploring the effect of stress on alcohol intake. Our findings highlight the immediate need for interventions focused on stress-reduction in order to diminish heavy episodic drinking among undergraduate students and, thereby, reduce the risk for future alcohol use disorders.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery Grant #203707) awarded to M.C.O.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciatively acknowledge Veronica Lee for assistance with data collection and Amanda Maracle for input regarding statistical analyses.