Abstract

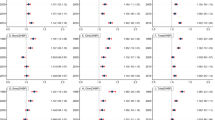

We evaluated income- and education-related inequalities in blood pressure, hypertension and hypertension treatment in the general population of Trinidad and Tobago. The design included survey of 300 households in north central Trinidad, including 631 adults in 2001. Measurements of blood pressure, weight, height, waist and hip circumferences, and educational attainment, household income and alcohol intake by questionnaire. The slope index of inequality (SII) was used to estimate the difference in blood pressure between those with highest, as compared to lowest, socioeconomic status. Complete measurements and questionnaires were obtained for 461 (73%) including 202 men and 259 women. In women, after adjusting for age and ethnicity, the SII for systolic blood pressure by income was −12.6, 95% confidence interval −22.6 to −2.6 mmHg (P=0.013); and −10.8 (−21.4 to −0.2) mmHg (P=0.045) by educational attainment. After additionally adjusting for body mass index, waist–hip circumference ratio and self-reported diabetes, the SII for income was −7.3 (−16.5 to 1.9) mmHg (P=0.120) and for educational attainment was −3.0 (−13.0 to 6.9) mmHg (P=0.551). In men, after adjusting for age and ethnicity, the SII for systolic blood pressure by income was −4.3 (−15.4 to 6.8) mmHg (P=0.447) and for education −8.1 (−19.0 to 2.8) (P=0.145). There is a negative association of systolic blood pressure with increasing income or education in women. This is associated with body mass index, abdominal obesity and diabetes. There is no consistent association between education or income and blood pressure in men.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. World Health Report 2002. Reducing Risks Promoting Healthy Life. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2002.

Colhoun H, Hemingway H, Poulter NR . Socio-economic status and blood pressure: an overview analysis. J Human Hypertens 1998; 12: 91–110.

Dressler WW, Grell GA, Gallagher PN, Viteri FE . Blood pressure and social class in a Jamaican community. Am J Public Health 1988; 78: 714–716.

Hutchinson J . Association between stress and blood pressure variation in a Caribbean population. Am J Phys Anthropol 1986; 71: 69–79.

Mendez MA et al. Income, education, and blood pressure in adults in Jamaica, a middle-income developing country. Int J Epidemiol 2003; 32: 400–408.

Gwatkin DR . Distributional implications of alternative strategic responses to the demographic epidemiological transition. An initial inquiry. In: Gribble JN, Preston SH (eds). The Epidemiological Transition. Policy and Planning Implications for Developing Countries. National Academy Press: Washington DC, 1993, pp 197–228.

Ebrahim S, Smith GD . Exporting failure? Coronary heart disease and stroke in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 2001; 30: 201–205.

World Bank. World Development Indicators 2002. World Bank: Washington DC, 2002. Available http://www.worldbank.org/data/wdi2002/tables/table1-1.pdf accessed 3rd March 2003.

Gulliford MC, Mahabir D, Rocke B . Food insecurity, food choices and body mass, index in adults: nutrition transition in Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Epidemiol 2003; 32: 508–516.

Colhoun H, Prescott-Clarke P . Health Survey for England 1994. HMSO: London, 1996.

Babor TF, Ramon de la Fuente J, Saunders J, Grant M . AUDIT. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1992.

Gillum RF, Mussolino ME, Ingram DD . Physical activity and stroke incidence in women and men. The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol 1996; 143: 860–869.

Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. Central Statistical Office. 1990 Population and Housing Census. Volume 2. Age Structure, Religion, Ethnic Group, Education. Office of the Prime Minister, Central Statistical Office: Port of Spain, 1994.

Gulliford MC et al. Overweight, obesity and skinfold thicknesses of children of African or Indian descent in Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Epidemiol 2001: 30: 989–998.

O'Brien E, Mee F, Atkins N, Thomas M . Evaluation of three devices for self-measurement of blood pressure according to the revised British Hypertension Society protocol: the Omron HEM 705 CP, Philips HP5332 and Nissei DS-176. Blood Pressure Monit 1996; 1: 55–61.

Wagstaff A, Paci P, van Doorslaer E . On the measurement of inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med 1991; 33: 545–557.

Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE . Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med 1997; 44: 757–771.

Stata Corporation. Stata Reference Manual. Release 7. Stata Corporation: College Station, TX, 2001.

Gribble JN, Preston SH . The Epidemiological Transition. Policy and Planing Implications for Developing Countries. National Academy Press: Washington DC, 1993.

Mackenbach JP . The epidemiologic transition theory. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994; 48: 329–331.

Chang C, Marmot MG, Farley TMM, Poulter NR . The influence of economic development on the association between education and the risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke. J Clin Epidemiol 2002; 55: 741–747.

Sobal J, Stunkard AJ . Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull 1989; 105: 260–275.

Kaufman JS et al. Determinants of hypertension in West Africa: contribution of anthropometric and dietary factors to urban–rural and socioeconomic gradients. Am J Epidemiol 1996; 143: 1203–1218.

Gulliford MC . Epidemiological transition and socio-economic inequalities in blood pressure in Jamaica. Int J Epidemiol 2003; 32: 408–409.

Nogueira A et al. Socioeconomic-status and risk-factors for cardiovascular-disease—a multicenter collaborative study in the international clinical epidemiology network (INCLEN). J Clin Epidemiol 1994; 47: 1401–1409.

Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Popkin BM . Independent effects of income and education on the risk of obesity in the Brazilian adult population. J Nutr 2001; 131: 881S–886S.

Shaper AG . Hypertension in populations of African origin—annotation. Am J Public Health 1997; 87: 155–156.

Bovet P et al. Distribution of blood pressure, body mass, index and smoking habits in the urban population of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and associations with socioeconomic status. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 240–247.

Gulliford MC, Mahabir D . Social inequalities in morbidity from diabetes mellitus in public primary care clinics in Trinidad and Tobago. Soc Sci Med 1998; 46: 137–144.

Gulliford MC et al. Social environment, morbidity and use of health care among people with diabetes mellitus in Trinidad. Int J Epidemiol 1997; 26: 620–627.

Cruickshank JK et al. Hypertension in four African-origin populations: current ‘Rule of Halves’, quality of blood pressure control and attributable risk of cardiovascular disease. J Hypertens 2001; 19: 41–46.

Gulliford MC, Mahabir D . Utilisation of private care by public primary care clinic attenders with diabetes: relationship to health status and social factors. Soc Sci Med 2001; 53: 1045–1056.

Gulliford MC et al. Diabetes care in middle income countries: a Caribbean case study. Diabet Med 1996; 13: 574–581.

Singh-Manoux A, Clarke P, Marmot M . Multiple measures of socio-economic position and psychosocial health: proximal and distal measures. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 1192–1199.

Reaven GM . Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988; 37: 1595–1607.

Lang T . Can the challenges of poverty, sustainable consumption and good health governance be addressed in an era of globalisation? In: Caballero B, Popkin BM (eds). The Nutrition Transition. Diet and Disease in the Developing World. Academic Press: London, 2003, pp 51–70.

Murray CJL et al. Effectiveness and costs of interventions to lower systolic blood pressure and cholesterol: a global and regional analysis on reduction of cardiovascular-disease risk. Lancet 2003; 361: 717–725.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Chief Medical Officer of Trinidad and Tobago for permission to report this work. We also thank the staff of the Central Statistical Office for help in drawing the sample and for advice on conducting the survey, the Principal Medical Officer (Community Services), and the staff of the Nutrition Division for their skill and dedication in working on the survey.

Dr Mahabir had the original idea for the survey and contributed to the design and implementation of the study, Mr Rocke contributed to the design of the study and oversaw the collection of data, Dr Gulliford designed the questionnaire and measurement forms, analysed the data and drafted the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper. Dr Gulliford and Dr Mahabir are joint guarantors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gulliford, M., Mahabir, D. & Rocke, B. Socioeconomic inequality in blood pressure and its determinants: cross-sectional data from Trinidad and Tobago. J Hum Hypertens 18, 61–70 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001638

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001638

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

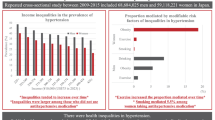

Regional economic development, household income, gender and hypertension: evidence from half a million Chinese

BMC Public Health (2020)

-

Health inequalities in hypertension and diabetes management among the poor in urban areas: a population survey analysis in south Korea

BMC Public Health (2016)

-

Educational inequalities in hypertension: complex patterns in intersections with gender and race in Brazil

International Journal for Equity in Health (2016)

-

Disparities in hypertension among black Caribbean populations: a scoping review by the U.S. Caribbean Alliance for Health Disparities Research Group (USCAHDR)

International Journal for Equity in Health (2015)

-

Assessing socioeconomic inequalities of hypertension among women in Indonesia's major cities

Journal of Human Hypertension (2015)