Abstract

Background:

No data exist on the population prevalence of, or risk factors for, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in predominantly Muslim countries in Asia.

Methods:

Cervical specimens were obtained from 899 married women aged 15–59 years from the general population of Karachi, Pakistan and from 91 locally diagnosed invasive cervical cancers (ICCs). HPV was detected using a GP5+/6+ PCR-based assay.

Results:

The prevalence of HPV in the general population was 2.8%, with no evidence of higher HPV prevalence in young women. The positivity of HPV was associated with women's lifetime number of sexual partners, but particularly with the age difference between spouses and other husbands’ characteristics, such as extramarital sexual relationships and regular absence from home. The HPV16/18 accounted for 24 and 88% of HPV-positive women in the general population and ICC, respectively.

Conclusion:

Cervical cancer prevention policies should take into account the low HPV prevalence and low acceptability of gynaecological examination in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

To date, there are no data on the population prevalence of, or risk factors for, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in predominantly Muslim countries in Asia, where sexual mores differ from many other world populations (Wellings et al, 2006). These data are essential to assess the potential relevance of HPV vaccination and HPV test-based screening to invasive cervical cancer (ICC) prevention in the region, as well as to identify any changes in risk occurring in young generations. Thus, a study of women with and without cervical cancer was carried out in Karachi, Pakistan, according to the standardised protocol of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) HPV Prevalence Surveys (Clifford et al, 2005), which was approved by both the IARC and local ethical review committees.

Methods

A total of 3882 married women aged 15–59 years living in Orangi, a densely populated suburb of Karachi, were visited at their homes and invited to join the study, with the aim to enrol ∼100 women in each 5-year age group. Participation rates were 24.1, 25.7, 25.1 and 23.6% among women aged 15–24, 25–34, 35–44 and 45–59 years, respectively. All participants signed an informed consent form and were administered a questionnaire. In all, 915 participants came to the study clinic located in the Sindh Government Qatar Hospital, where a sample of exfoliated cervical cells was collected and placed into PreservCyt media (Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA) for HPV testing and liquid-based cytology.

In parallel, formalin-fixed tumour biopsies were retrieved from women presenting with histologically confirmed ICC between 2004 and 2008 to the Ziauddin and Aga Khan University Hospitals, Karachi. After exclusion of 40 biopsies that were β-globin negative and/or without histological evidence of tumour, 91 ICCs remained (79 squamous cell, 3 adeno, 4 small cell and 5 other or unspecified carcinomas).

Liquid-based cytology and HPV testing were carried out at the Vrije University, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. A general primer GP5+/6+-mediated PCR was used for the detection of 44 genital HPV types (Jacobs et al, 2000). Subsequent HPV typing was carried out by reverse-line blot hybridisation of PCR products (van den Brule et al, 2002). Odds ratios (ORs) for HPV positivity were calculated by unconditional logistic regression adjusted for age, with OR trends assessed by considering categories as continuous variables.

Results

Among 899 women from the general population with valid cytology and HPV results, HPV prevalence was 2.8% (Table 1). Cervical abnormalities were diagnosed in 2.4% of women, of whom 27.3% were HPV-positive. They included 19 atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (4 HPV-positive), 1 low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HPV16/66-positive) and 2 high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (1 HPV-negative; 1 HPV16-positive, later revealed to be ICC). HPV16 was confirmed as the most common type among women with both normal (0.5%) (Clifford et al, 2005) and abnormal (9.1%) cytology. HPV16 was also the predominant HPV type (75.8%) in ICC, followed by HPV18 (6.6%) and 45 (4.4%) (Table 1).

Having ⩾2 lifetime sexual partners was reported by 5.6% of women, and was significantly associated with HPV positivity (OR=3.36; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.08–10.41), as was being a working woman (OR=3.01; 95% CI: 1.26–7.21) (Table 2). In addition, HPV infection was strongly associated with husbands’ characteristics, such as extramarital sexual relationships (OR=4.40; 95% CI: 1.83–10.56), absence from home >7 nights per month (OR=4.84; 95% CI: 1.30–17.95) and a ⩾10 year age difference between spouses (OR=6.88; 95% CI: 1.48–31.94) (Table 2). Husbands’ characteristics were correlated with each other, but associations were unaffected by adjustment for women's lifetime number of sexual partners.

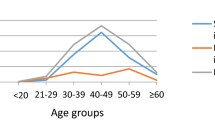

The positivity of HPV did not vary significantly by age (Table 2). Neither were there any significant associations with education level, marital status, number of full-term pregnancies, age at sexual debut (Table 2), language/ethnic group (87.5% Urdu speakers), birth outside Karachi (44.9%), use of condom (19.7%), hormonal contraceptives (16.7%) and intrauterine device (7.2%), tubal ligation (5.2%), history of spontaneous (35.2%) or induced (11.5%) abortions, smoking (1.7%) or previous Pap smear (1.1%) (data not shown).

Discussion

This study disclosed a very low burden of HPV infection in the general female population of Karachi, considerably lower than that found using similar protocols in nearby India (17%) (Franceschi et al, 2005), China (15–18%) (Dai et al, 2006; Li et al, 2006; Wu et al, 2007) and Nepal (9%) (Sherpa et al, 2010), and >10-fold lower than in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., 51% in Guinea, also a predominantly Muslim country) (Keita et al, 2009). There was no evidence of higher prevalence in younger women, confirming the flat age-specific curve seen in other low-resource countries in Asia and Africa (Franceschi et al, 2006), although at much lower HPV prevalence. An HPV prevalence of 27.3% in cervical abnormalities is also low compared with high-resource settings (IARC, 2005), highlighting problems in specificity of even gold-standard cytology in settings of very low HPV prevalence.

The HPV16 accounted for three-quarters of ICC in Pakistan, confirming the high prevalence of HPV16 observed in ICC from the Indian subcontinent compared with other world regions (Franceschi et al, 2003; Basu et al, 2009; Gheit et al, 2009). Indeed, our data would suggest that the predominance of HPV16 over other high-risk types might be even greater in settings of low HPV exposure.

Major study strengths include a large population-based sample, use of a standardised and well-validated HPV test allowing comparisons with similar studies around the world (Clifford et al, 2005) and with a concurrent series of ICC from the same area. The main limitation, which was nevertheless an important finding in itself, was the low participation rate, for which the principal reasons were lack of husband's permission and/or lack of appreciation of screening in the absence of symptoms. As HPV infection is asymptomatic, it is unlikely that participation was highly correlated to HPV positivity. However, hesitancy to undergo gynaecological examination would be a strong obstacle to any future cervical cancer screening efforts in Pakistan (Imam et al, 2008). Furthermore, vaginal examination was acceptable only to married women, as in similar surveys in Asia (Franceschi et al, 2005; Dai et al, 2006; Sherpa et al, 2010). Nevertheless, 98.2% of women reported an age at sexual debut concurrent with, or just after, age at marriage, suggesting that marriage may be a good proxy of sexual debut in this population.

In conclusion, the low HPV prevalence in this study is consistent with the low ICC risk estimate from Karachi (7.5/100 000 cases annually; rarer than the breast, mouth, ovary and oesophagus) (Curado et al, 2007) and other predominantly Muslim countries in Asia (Curado et al, 2007) and, reassuringly, there is no evidence that HPV prevalence is higher in young generations of urban women. However, 80% of the ICC that do develop in this population (of which one was newly diagnosed by our study) are attributable to HPV16/18. These findings should be taken into account when considering the cost-effectiveness of ICC prevention modalities in a population in which the burden of HPV and other sexually transmitted infections (Zaheer et al, 2009) seems low, but the burden of many other chronic infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis (Hasan et al, 2009) and hepatitis C virus (Ahmad, 2004)) is high.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Ahmad K (2004) Pakistan: a cirrhotic state? Lancet 364: 1843–1844

Basu P, Roychowdhury S, Bafna UD, Chaudhury S, Kothari S, Sekhon R, Saranath D, Biswas S, Gronn P, Silva I, Siddiqi M, Ratnam S (2009) Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in cervical cancer in India: results from a multi-center study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 10: 27–34

Clifford GM, Gallus S, Herrero R, Muñoz N, Snijders PJ, Vaccarella S, Anh PT, Ferreccio C, Hieu NT, Matos E, Molano M, Rajkumar R, Ronco G, de Sanjosé S, Shin HR, Sukvirach S, Thomas JO, Tunsakul S, Meijer CJ, Franceschi S, the IARC HPV Prevalence Surveys Study Group (2005) Worldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: a pooled analysis. Lancet 366: 991–998

Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR, Storm H, Ferlay J, Heanue M, Boyle P (2007) Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. IX. IARC Scientific Publication No. 160. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon

Dai M, Bao YP, Li N, Clifford GM, Vaccarella S, Snijders PJF, Huang RD, Sun LX, Meijer CJLM, Qiao YL, Franceschi S (2006) Human papillomavirus infection in Shanxi Province, People's Republic of China: a population-based study. Br J Cancer 95: 96–101

Franceschi S, Herrero R, Clifford GM, Snijders PJ, Arslan A, Anh PT, Bosch FX, Ferreccio C, Hieu NT, Lazcano-Ponce E, Matos E, Molano M, Qiao YL, Rajkumar R, Ronco G, de Sanjosé S, Shin HR, Sukvirach S, Thomas JO, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N, the IARC HPV Prevalence Surveys Study Group (2006) Variations in the age-specific curves of human papillomavirus prevalence in women worldwide. Int J Cancer 119: 2677–2684

Franceschi S, Rajkumar R, Snijders PJF, Arslan A, Mahé C, Plummer M, Sankaranarayanan R, Cherian J, Meijer CJLM, Weiderpass E (2005) Papillomavirus infection in rural women in southern India. Br J Cancer 92: 601–606

Franceschi S, Rajkumar T, Vaccarella S, Gajalakshmi V, Sharmila A, Snijders PJ, Muñoz N, Meijer CJ, Herrero R (2003) Human papillomavirus and risk factors for cervical cancer in Chennai, India: a case-control study. Int J Cancer 107: 127–133

Gheit T, Vaccarella S, Schmitt M, Pawlita M, Franceschi S, Sankaranarayanan R, Sylla BS, Tommasino M, Gangane N (2009) Prevalence of human papillomavirus types in cervical and oral cancers in central India. Vaccine 27: 636–639

Hasan R, Jabeen K, Mehraj V, Zafar F, Malik F, Hassan Q, Azam I, Kadir MM (2009) Trends in Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance, Pakistan, 1990–2007. Int J Infect Dis 13: e377–e382

IARC (2005) IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention Volume 10: Cervix Cancer Screening. IARC Press: Lyon

Imam SZ, Rehman F, Zeeshan MM, Maqsood B, Asrar S, Fatima N, Aslam F, Khawaja MR (2008) Perceptions and practices of a Pakistani population regarding cervical cancer screening. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 9: 42–44

Jacobs MV, Walboomers JM, Snijders PJ, Voorhorst FJ, Verheijen RH, Fransen-Daalmeijer N, Meijer CJ (2000) Distribution of 37 mucosotropic HPV types in women with cytologically normal cervical smears: the age-related patterns for high-risk and low-risk types. Int J Cancer 87: 221–227

Keita N, Clifford GM, Koulibaly M, Douno K, Kabba I, Haba M, Sylla BS, van Kemenade FJ, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Franceschi S (2009) HPV infection in women with and without cervical cancer in Conakry, Guinea. Br J Cancer 101: 202–208

Li LK, Dai M, Clifford GM, Yao WQ, Arslan A, Li N, Shi JF, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Qiao YL, Franceschi S (2006) Human papillomavirus infection in Shenyang City, People's Republic of China: a population-based study. Br J Cancer 95: 1593–1597

Sherpa ATL, Clifford G, Vaccarella S, Shrestha S, Nygård N, Karki BS, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Franceschi S (2010) Human papillomavirus infection in women with and without cervical cancer in Nepal. Cancer Causes Control 21: 313–330

van den Brule AJ, Pol R, Fransen-Daalmeijer N, Schouls LM, Meijer CJ, Snijders PJ (2002) GP5+/6+ PCR followed by reverse line blot analysis enables rapid and high-throughput identification of human papillomavirus genotypes. J Clin Microbiol 40: 779–787

Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E, Singh S, Hodges Z, Patel D, Bajos N (2006) Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet 368: 1706–1728

Wu RF, Dai M, Qiao YL, Clifford GM, Liu ZH, Arslan A, Li N, Shi JF, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Franceschi S (2007) Human papillomavirus infection in women in Shenzhen City, People's Republic of China, a population typical of recent Chinese urbanisation. Int J Cancer 121: 1306–1311

Zaheer HA, Hawkes S, Buse K, O’Dwyer M (2009) STIs and HIV in Pakistan: from analysis to action. Sex Transm Infect 85 (Suppl 2): ii1–ii2

Acknowledgements

The work was undertaken by Dr Syed Ahsan Raza during the tenure of an International Postdoctoral Fellowship at the International Agency for Research on Cancer and was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, USA (grant number 35537); the Association for International Cancer Research, UK (project grant number 08-0213); and the Institut National du Cancer, France (convention de recherche 07/3D1514/PL-89-05/NG-LC). We thank Dr Hamid Manzoor for coordinating the study at Sindh Government Qatar Hospital in Karachi and the team of midwives at the clinic and field site, and Anwar Kamal of ‘The Lab-Saddar’ in Karachi for technical assistance. We are grateful to Dr Arshad Altaf of Canada–Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project for his advice during the survey in Karachi; as well as Dr Aliya Aziz, Associate Professor, Department of Gynecology & Obstetrics, and Dr Anwar Siddiqui, Associate Dean of Research, and Research Office of Aga Khan University in Karachi for their advice and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Raza, S., Franceschi, S., Pallardy, S. et al. Human papillomavirus infection in women with and without cervical cancer in Karachi, Pakistan. Br J Cancer 102, 1657–1660 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605664

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605664

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Detection of high-risk human papillomavirus infected cervical biopsies samples by immunohistochemical expression of the p16 tumor marker

Archives of Microbiology (2024)

-

Human papillomavirus spectrum of HPV-infected women in Nigeria: an analysis by next-generation sequencing and type-specific PCR

Virology Journal (2023)

-

Oral-genital HPV infection transmission, concordance of HPV genotypes and genital lesions among spouses/ partners of patients diagnosed with HPV-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC): a scoping review

Infectious Agents and Cancer (2023)

-

Investigating Bangladeshi Rural Women’s Awareness and Knowledge of Cervical Cancer and Attitude Towards HPV Vaccination: a Community-Based Cross-Sectional Analysis

Journal of Cancer Education (2022)

-

HPV Genotypes distribution in Indian women with and without cervical carcinoma: Implication for HPV vaccination program in Odisha, Eastern India

BMC Infectious Diseases (2017)