Abstract

Skin malignancy is an important cause of mortality in the United Kingdom and is rising in incidence every year. Most skin cancer presents in primary care, and an important determinant of outcome is initial recognition and management of the lesion. Here we present an observational study of interobserver agreement using data from a population-based randomised controlled trial of minor surgery. Trial participants comprised patients presenting in primary care and needing minor surgery in whom recruiting doctors felt to be able to offer treatment themselves or to be able to refer to a colleague in primary care. They are thus relatively unselected. The skin procedures undertaken in the randomised controlled trial generated 491 lesions with a traceable histology report: 36 lesions (7%) from 33 individuals were malignant or pre-malignant. Chance-corrected agreement (κ) between general practitioner (GP) diagnosis of malignancy and histology was 0.45 (0.36–0.54) for lesions and 0.41 (0.32–0.51) for individuals affected with malignancy. Sensitivity of GPs for the detection of malignant lesions was 66.7% (95% confidence interval (CI), 50.3–79.8) for lesions and 63.6% (95% CI, 46.7–77.8) for individuals affected with malignancy. The safety of patients is of paramount importance and it is unsafe to leave the diagnosis and treatment of potential skin malignancy in the hands of doctors who have limited training and experience. However, the capacity to undertake all of the minor surgical demand works demanded in hospitals does not exist. If the capacity to undertake it is present in primary care, then the increased costs associated with enhanced training for general medical practitioners (GPs) must be borne.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The United Kingdom has a health service divided into two distinct components. The large majority of people are registered with a GP who is the first point of contact with the service. There is no direct route to secondary care except through private consultation for a minority, or through the emergency room. Ever since the 1990 contract for GPs in England and Wales that specified an item of service payment for minor surgical procedures, there has been fierce debate about the quality and appropriateness of management decisions and clinical practices in general practice, focussing around two issues (Paraskevopoulos et al, 1988; Department of Health & The Welsh Office, 1989; Brazier and Lowy, 1991; Bull et al, 1991; McWilliam et al, 1991; Brown et al, 1992; Cox et al, 1992; Bricknell, 1993; Lowy et al, 1997, 1998; Cross, 1998; Khorshid et al, 1998; Kirby et al, 1998; Suvarna et al, 1998). First is the technical quality of surgery performed, discussed most often in terms of incomplete excision of malignant or pre-malignant conditions, and which we have addressed in a population-based randomised controlled trial of minor surgery (George et al). Intimately associated with this is the second issue, the accuracy of clinical diagnosis and the consequent need for histological confirmation of diagnosis. Until now, there has been a relative absence of firm UK evidence: what evidence exists comprises descriptions of personal case series from general practice, and audits of completely or incompletely excised lesions reported by pathologists, with or without accurate diagnoses recorded on the pathologist's request form.

In a population-based randomised controlled trial of minor surgery, we identified that GPs make less use of pathology services than do hospital doctors (George et al). We have been unable to identify population-based studies comparing clinical diagnosis in primary care and laboratory histology in the United Kingdom. This paper aims to establish how well GPs recognise skin cancer, using data from our trial.

Materials and methods

Data

This study used data on pathological samples collected during a population-based randomised controlled trial comparing the quality of minor surgery performed by GPs and hospital doctors (George et al). All patients recruited to the trial had a GP referral form indicating a working diagnosis for the lesion concerned. These working diagnoses were entered into a database, along with the histological diagnosis found on the histology form pertaining to the sample, where one was found. Multiple searches were undertaken in each of the pathology departments serving the area from which patients were recruited over the whole period of the trial to find these reports. There were many diagnoses on both referral forms and pathology reports, and we divided them into 23 categories, using a classification derived from Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, Sixth edition (Champion et al, 1998). The categories arrived at are shown in Tables 1 and 2. We excluded ingrowing toenails from all aspects of the ensuing analysis, leaving 22 categories of lesion. These were further collapsed into ‘benign’ and ‘malignant’ categories for analysis. The ‘malignant’ category comprised three malignancies (malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma), one low-grade malignancy (keratoacanthoma) and one pre-malignant condition (Bowen's disease).

Analysis

Chance-corrected, inter-rater reliability was measured using Cohen's κ in Stata 9.0 (Stata Corp). A κ value greater than 0.75 is considered excellent agreement beyond chance, values below 0.40 represent poor agreement, and values between 0.40 and 0.75 represent fair-to-good agreement (Fleiss, 1981). The sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value for GPs’ recognition of skin malignancies were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We did not run a sensitivity analysis on the data as missing cases greatly outnumbered known malignancies, and it was felt that the assumption that all missing cases were malignant was unlikely. In the group of malignancies in which surgery was undertaken by the GP, we used cross-tabulation to examine whether recognition of the lesion as malignant had an effect on completeness of excision.

Results

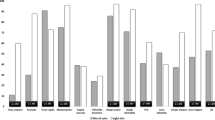

Five hundred and sixty-eight individuals entered the trial, which generated these data by 82 GPs. Their average age was 48.75 years, and 309 of them (54.4%) were women. Sixty-five GPs undertook surgery in the primary care arm of the trial and 60 hospital surgeons or dermatologists in the hospital arm. Of 705 lesions, 654 can be shown to have been subject to a procedure, 17 of these involving ingrowing toenails in which histology is not usually performed and which were excluded from later analysis. Overall, 491 of the 637 skin procedures (77%) generated a traceable pathology report. Table 1 shows numbers of these cases by diagnosis as described by the GPs and number in each category in which a histological sample was found by trial arm. In one case, there was no referral from the GP, the procedure having been performed at the request of a patient with multiple lesions and in whom that lesion had not been mentioned in the referral. This lesion was excluded, leaving 490 for further analysis. The table demonstrates that the deficit in samples does not follow a random pattern. However, although it might be expected that skin tags would be under-represented, shortfalls in other categories, which can sometimes closely resemble malignancies (e.g. basal cell papillomata, melanocytic naevi), are more worthy of concern. Table 2 shows the numbers of cases in which a histological sample was found as described by GPs and as classified by histological examination (ingrowing toenails excluded).

Agreement between GP diagnosis and histology

An overall κ statistic of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.36–0.54) was obtained for agreement between GP diagnosis and later histology. Even at its upper 95% CI, therefore, agreement is moderate at best. Four of the lesions (all basal cell carcinomas) were diagnosed, correctly, in the same individual, and it may be possible that the finding of one malignancy lesion pre-disposes the examiner to find others. If κ is recalculated to reflect individuals correctly diagnosed with malignancy, rather than lesions, the resulting statistic is 0.41 (0.32–0.51). Again, even at the upper level of statistical confidence, agreement is ‘moderate’ at best.

Test characteristics of GPs in detecting skin malignancy

The results above can be expressed as 2 × 2 tables and test characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, predictive values) were computed. Sensitivity is calculated as the proportion (or percentage) of malignancies correctly diagnosed, whereas specificity is the proportion (or percentage) of non-malignancies correctly diagnosed. A positive predictive value is the proportion of positive diagnoses that correctly identify a malignancy and a negative predictive value the proportion (or percentage) of negative diagnoses that correctly exclude one. Table 3 shows the data for individual lesions, with test characteristics computed below, and Table 4 is the analogous table for individuals affected with malignancy. The results do not differ a great deal between the two analyses. They indicate that, in our population, GPs failed to recognise one-third of the skin malignancies, or slightly more than one-third of the patients with malignancies. Taking statistical uncertainty into account, the upper 95% CI for both analyses indicates that they miss no fewer than one in five. Neither of the malignant melanomas included here was diagnosed by the GP concerned: one was described as a ‘dermatofibroma’ and the other given a general description as ‘red lesion’. A further two malignancies do not form part of this data set: although randomised they were lost to follow-up because hospital doctors judged that they did not meet an inclusion criterion, which was that the GPs should feel to be able to offer treatment themselves or to be able to refer to a colleague in primary care. Neither case was felt to be suitable for treatment within the context of a hospital minor surgery unit, and both were referred for specialist treatment. One was a squamous cell carcinoma in a ‘difficult’ area and the other a large malignant melanoma that had presented on multiple occasions before referral.

Discussion

Not all malignant lesions are clinically obvious at presentation, and some have potentially serious adverse outcomes if missed. In this study, GPs missed a third of malignancies, including both malignant melanomas, and two further malignancies were excluded at an earlier stage because of the lack of recognition of what they were. Clearly, more study is required: these data were collected in the highly artificial environment of a controlled trial and, despite some evidence to the contrary, it may be that all the malignancies unrecognised here would have been referred to specialist care under a 2-week waiting rule in a real-world situation. However, although confined to one geographical area of the United Kingdom, this study was population based and included patients referred by a large number of GPs, and we believe the results to be generalisable. It is reassuring for us, but perhaps not for patients, that our results are echoed in studies from other countries. Whited et al (1997) showed that primary care clinicians identified the presence of skin cancer with a sensitivity of 57% (95% CI, 44–68%) in one US study and concluded that ‘Without improved diagnostic skills, primary care clinicians’ examinations may be ineffective as a screening test’. Youl et al (2007) in Australia found that although, overall, sensitivity for diagnosing any skin cancer was similar for skin cancer clinic doctors (94%) and GPs (91%), sensitivity was higher for skin cancer clinic doctors for BCC (89 vs 79%; P<0.01) and melanoma (60 vs 29%; P<0.01). Raasch (1999), again in Australia, showed a sensitivity of 69.1% (95% CI, 62.5–75.7%) for primary care doctors in a series of non-melanoma skin malignancies. But what should the sensitivity be? Perfection, after all, is not easy to attain. True comparisons between dermatologists’ and primary care physicians’ accuracy in diagnosing melanoma are uncommon, but one systematic review showed a bottom end of the range of values of sensitivity to malignant melanoma in dermatologists of 81%, but of only 41% in primary care physicians (Chen et al, 2001). In the face of rising skin cancer incidence it is clear that the major challenge of providing minor surgery in primary care is the potential for missed diagnosis of serious skin malignancies (Diffey, 2004).

The 1990 contract was changed in 2004 so that there are stringent standards in place for those wishing to become general practitioners with a special interest in dermatology (Shekelle, 2003). However, these individuals, analogous to the ‘skin cancer clinic doctors’ in the study by Youl et al (2007), are not sufficient in number to undertake the assessment of all minor skin lesions presenting in primary care, and hospital services do not have the capacity either. GPs who merely wish to be added to the minor surgery list now have to be signed off by their trainer as competent, competent, but standards are set locally. Clinical guidelines issued by NICE make recommendations for referral of patients with suspected cancer from primary care to specialist services (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006). These guidelines recommend that patients presenting with skin lesions suggestive of skin cancer, or in whom a biopsy has been confirmed, should be referred to a team specialising in skin cancer. However, it is not clear what will happen if GPs do not suspect that a lesion is cancerous, as in one-third of the malignancies in this study.

These results place an important ‘health warning’ around the assumption that shifting services from secondary care to primary care carries only benefits (Department of Health, 2006). There is not the capacity in hospitals to take on the workload of minor surgery or even of mere diagnosis of all skin lesions, and it would likely be unpopular with patients if it were to happen (George et al). We do not believe that the background of a doctor in general practice, surgery or even dermatology is fundamentally important, but we do believe that it is unsafe to leave the diagnosis and treatment of potential skin cancer entirely in the hands of doctors who have had insufficient training to do it. The increased costs associated with developing and delivering appropriate training to all GPs, not just for those with a specialist interest, must be acknowledged and provided.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Brazier J, Lowy A (1991) Performance of skin biopsies by general practitioners. BMJ 303: 1472

Bricknell MC (1993) Skin biopsies of pigmented skin lesions performed by general practitioners and hospital specialists. Br J Gen Pract 43: 199–201

Brown PA, Kernohan NM, Smart LM, Savargaonkar P, Atkinson P, Robinson S, Russell D, Kerr KM (1992) Skin lesion removal: practice by general practitioners in Grampian Region before and after April 1990. Scott Med J 37: 144–146

Bull AD, Silcocks PB, Start RD, Kennedy A (1991) Performance of skin biopsies by general practitioners. BMJ 303: 1473

Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM (1998) ‘Rook/Wilkinson/Ebling. Textbook of Dermatology’. Blackwell Scientific: Oxford

Chen SC, Bravata DM, Weil E (2001) A comparison of dermatologists’ and primary care physicians’ accuracy in diagnosing melanoma. Arch Dermatol 137: 1627–1634

Cox NH, Wagstaff R, Popple AW (1992) Using clinicopathological analysis of general practitioner skin surgery to determine educational requirements and guidelines. BMJ 304: 93–96

Cross P (1998) Is histological examination of tissue removed by GPs always necessary? Even specialists get the clinical diagnosis wrong. BMJ 316: 778

Department of Health (2006) Our health, Our Care, Our Say: A New Direction for Community Services. HMSO: London

Department of Health and The Welsh Office (1989) General Practice in the National Health Service, the 1990 contract. The Government's Program for Changes to General Practitioners’ Terms and Conditions of Service and Remunerative Systems. HMSO: London

Diffey BL (2004) The future incidence of cutaneous melanoma within the UK. Br J Dermatol 151: 868–872

Fleiss JL (1981) ‘Measurement of Inter-Rater Agreement’ Chapter 13 of ‘Statistical methods for rates and proportions’ (2nd edn), Wiley series in probability and mathematical statistics: New York

George S, Pockney P, Primrose J, Smith H, Little H, Kinley H, Kneebone R, Lowy A, Leppard B, Jayatilleke N, McCabe C . A prospective randomised comparison of minor surgery in primary and secondary care. The MiSTIC trial Health Technol Assess 2008; 12 (23): 1–58

Khorshid SM, Pinney E, Newton-Bishop JA (1998) Melanoma excision by general practitioners in north-east Thames region, England. Br J Dermatol 138: 412–417

Kirby B, Harrison P, Blewitt R (1998) Is histological examination of tissue removed by GP's always necessary. More skin carcinomas might be detected with routine histological examination. BMJ 316: 779

Lowy A, Abrams K, Willis D (1998) Is histological examination of tissue removed by general practitioners always necessary? BMJ 316: 779

Lowy A, Willis D, Abrams K (1997) Is histological examination of tissue removed by general practitioners always necessary? Before and after comparison of detection rates of serious skin lesions. BMJ 315: 406–408

McWilliam LJ, Knox F, Wilkinson N, Oogarah P (1991) Performance of skin biopsies by general practitioners. BMJ 303: 1177–1179

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2006) Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Outcomes for People with Skin Tumours including Melanoma. The Manual. NICE: London

Paraskevopoulos JA, Hosking SW, Johnson AG (1988) Do all minor excised lesions require histological examination? Discussion paper. J R Soc Med 81: 583–584

Raasch BA (1999) Suspicious skin lesions and their management. Aust Fam Physician 28: 466–471

Shekelle P (2003) New contract for general practitioners. BMJ 326: 457–458

Suvarna SK, Shortland JR, Smith JHF (1998) Over 10 days two important lesions were sent to histopathologists in Sheffield. BMJ 316: 778–779

Whited JD, Hall RP, Simel DL, Horner RD (1997) Primary care clinicians’ performance for detecting actinic keratoses and skin cancer. Arch Intern Med 157: 985–990

Youl PH, Baade PD, Janda M, Del Mar CB, Whiteman DC, Aitken JF (2007) Diagnosing skin cancer in primary care: how do mainstream general practitioners compare with primary care skin cancer clinic doctors? MJA 187: 215–220

Acknowledgements

We thank the NHS Health Technology Assessment research and development programme for funding this study. However, the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the paper and the decision to submit the paper were the responsibilities of the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethics: South West Multi-site Research Ethics Committee.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pockney, P., Primrose, J., George, S. et al. Recognition of skin malignancy by general practitioners: observational study using data from a population-based randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 100, 24–27 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604810

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604810

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Minor surgery in general practice in Ireland- a report of workload and safety

BMC Family Practice (2020)

-

Steeds meer verdachte huidafwijkingen bij de huisarts

Huisarts en wetenschap (2015)

-

De rol van de huisarts bij huidtumoren

Huisarts en wetenschap (2015)

-

Skin lesions suspected of malignancy: an increasing burden on general practice

BMC Family Practice (2014)

-

Minor surgery in general practice and effects on referrals to hospital care: Observational study

BMC Health Services Research (2011)