Key Points

-

Demonstrates the use made by members of the public in obtaining oral health advice from pharmacists.

-

Recommendations/proposals for PCTs on improving the oral healthcare provision by their pharmacies.

-

A useful analysis for comparison for pharmacists and GDPs in the UK.

-

Identifies some of the recent Department of Health requirements for PCTs and pharmacists.

Abstract

Objectives To determine the existing state of oral healthcare advice, products and information provided by community pharmacies in Durham Dales Primary Care Trust area, and determine their potential role in the provision of oral healthcare services.

Methods A semi-structured questionnaire was devised to examine the current role of community pharmacies in oral healthcare. An interview was arranged with each of the pharmacies.

Results Ninety per cent of pharmacies participated from the Trust area. Common presenting complaints were ulcers and toothache/pain relief. Pharmacists advised customers to see a dentist in 94.1% of cases, 23.5% to see a doctor, 41.2% gave oral hygiene advice and 100% gave short-term pain relief. Pharmacists were keen to improve oral health knowledge. Most were aware of the nearest dental practices but few knew arrangements for emergencies/appointments. There were 14 pharmacists wanting active roles in promotional activities and national campaigns. Issues raised were lack of known key contacts for referrals/advice and lack of support on integration into primary healthcare teams.

Conclusion Through new pharmacy contracts and support/education, pharmacists could perform an increased role in oral healthcare provision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The role of the community pharmacist in the provision of general and oral healthcare is an important and relevant one in view of the recent and impending national government strategies to improve the delivery of primary healthcare. There have been several initiatives by the Department of Health in the last few years to broaden the contributions made by community pharmacists in improving the range and quality of primary care services.1,2

In April 2000, Patient Group Directives (PGD) were introduced to primary care sectors. A PGD is a written direction relating to supply and/or administration of a prescription-only medication to persons generally. A PGD must be signed by a doctor or dentist and a pharmacist. This new legislation provides an opportunity for extending pharmacists' roles, whether they be pharmacists involved in the drawing up of PGDs or pharmacists authorised to supply or administer under PGD.1 The Wanless Report also published in April 2002 indicated there was a need to reassess what work could be undertaken by nurses and other healthcare professionals, including therapists and pharmacists.2

The latest Department of Health initiative is a consultation paper A vision for pharmacy in the new NHS3 — the new pharmacy contract. In this the government aims to encourage integration of pharmacists into the healthcare team and increase the range of services provided through the pharmacy contract. Total control of pharmacy services and budgets will be given to Primary Care Trusts in a move that will lead to the creation of innovative new pharmacist roles. The contract framework for this should be available by April 2004 and legislation is planned for 2005.

In the light of these new government directives, the aim of this study is to quantify the existing state of oral healthcare advice, products and information given by local community pharmacists in the Durham Dales Primary Care Trust area.

This would inform the development of oral healthcare services for local people in a community pharmacy context. The role of the community pharmacist can therefore be evaluated and strategies for enhancing their oral healthcare provision assessed.

The Durham Dales area is mainly a rural one therefore access to services can be poor.4 The area consists of two district councils, namely Teesdale and Wear Valley. Teesdale has an average population of 0.3 people per hectare and Wear Valley has an average of 1.2 people per hectare. In contrast the national average for England and Wales is 3.4 people per hectare.5 An improvement through a public health promotion initiative in pharmacies in this area therefore, is strategically very important. The aim would not be to diminish existing primary care services but to augment them, with a much wider range of routes for patients to take advice, more diagnostic equipment available and more treatment options. This would mean a greater proportion of diagnoses and treatments could take place in primary care settings, so reducing the time patients spend in acute care.

Chestnutt et al.6 discussed the potential contributions of pharmacy staff to dental and oral health in the changing face of pharmacies. They noted important deficiencies in the oral healthcare knowledge of pharmacists. Anderson7 published a discussion paper highlighting the need for pharmacists to be incorporated into a multi-disciplinary oral healthcare team. Neither of these papers involved an investigative study. An investigation published in 2001 compared the oral healthcare role of pharmacies with a group of drug users and a group of non-drug users.8 This research demonstrated that pharmacists already play an important role within 'special risk groups' as far as oral health is concerned which could be extended to include a much larger client base

Methods

All 18 pharmacies in the Durham Dales area were requested to participate in this study. An informal mailing to the pharmacies located those willing to help with the survey, 17 pharmacies agreed to take part. Each letter was followed up with a courtesy telephone call to arrange a mutually convenient time to visit. Oral healthcare questionnaires were devised with the help of the Local Pharmacy Committee advisor.

The questionnaires were divided into four basic sections. The first section requested details on numbers of staff available, independent or multiple, client use of the pharmacy and requests for advice. The second section enquired on the range of oral health products available and the basis for any particular product recommendations. The scale used to compare the relative stock quantities was devised by using a very large oral healthcare product retailer as the upper baseline.9 The third section tested knowledge of local dental practice whereabouts and appointment arrangements. The final section was about usage of pharmacies for promotional activities and improvements in passing on the oral health message to clients. In amongst all these, questions were aimed at locating the levels of confidence of pharmacists when involved in giving oral healthcare and their judgement about their continuing professional development needs. Each pharmacy was visited and the questionnaires discussed and completed.

Results

The participation rate in the study was 17 out of the 18 pharmacies contacted (89.5%). The independent versus multiple owned pharmacy ratios were 76.8% to 24% respectively. There was a predominance of independently owned pharmacies in the study area.

The mean number of staff working in the pharmacies was 5.14 people. Between 100-150 people on average visit an independent pharmacy on a daily basis. For multiple pharmacies the daily figures were 151-300 visits. Overall however between both categories 41.18% of pharmacies reported 100-150 visits daily and 38.9% reported 151-300 visits daily.

Approximately 41% of pharmacies reported more than 100 weekly requests for general health advice (Fig. 1).

However the number of people requesting oral health advice per week was variable, 67.4% of pharmacies reporting more than 11 requests (Fig. 1).

Question: What oral advice are these people requesting?

The oral health advice requests of the pharmacist were split up into sections which consisted of toothache/pain relief, ulcers, sore mouth, bleeding gums, teething, dentures or product advice, ie toothpastes, toothbrushes, mouthwashes, tooth-whitening. The most common complaints were ulcers and toothache/pain relief. The least advice was requested about toothbrushes and tooth whitening systems. These results were estimates made by the pharmacists only across the 17 shops (Table 1).

Question: Recommendations given by the pharmacist for a painful oral health problem.

Pharmacists advised the client to see a dentist in 94.1% of cases, to see a doctor in 23.5% of cases, oral hygiene advice was given in 41.2% of cases and 100% provided short-term pain relief (Fig. 2).

Question: Pharmacist confidence providing oral health care advice.

Seventy-one per cent of pharmacists said they were confident giving oral healthcare advice, 59.2% of independents and 75% of multiples. No pharmacists said they were not at all confident, however 29.4% said sometimes they were not confident enough.

The oral health products stocked at each of the 17 pharmacy shops were included in the survey. For almost every product the pharmacies fell into the lowest quantity bracket of the survey. Some exceptions were mouthwashes, floss, dental gum/breath fresheners and denture care products (Table 2).

Pharmacists were asked which of eight responses they would give when asked to recommend a suitable oral healthcare product. None of the pharmacists said they would respond with 'don't know'. From the results most recommended on their own personal experience of a product or based on training courses they had attended (Fig. 3).

There were positive responses from pharmacists when asked about developing their knowledge through courses or oral health programmes. None of the pharmacists were completely uninterested in courses however 35.3% did issue concerns as to expense, timing and location of courses.

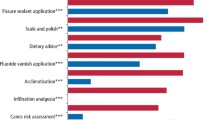

Information was sought from the pharmacists on the location of their nearest dental practice and their relevant appointment arrangements. The majority knew where their nearest practice was located but knew little of the necessary arrangements (Fig. 4).

The pharmacists were asked how enthusiastic they would be if asked to participate in oral health promotional activities in the store. The answers differed depending on whether the pharmacist belonged to an independent or multiple owned pharmacy. Nearly all the pharmacists were keen to take part if asked, however the multiples specified that their head offices would have to be approached first and may not agree, 82.4% were very enthusiastic, 5.9% would definitely not and 11.8% specified that head office would have to be contacted beforehand.

An open question at the end of the questionnaire for pharmacists to put forward any ideas they may have where we could help them improve their oral health service to meet the needs of their local communities. The most frequently suggested ideas are listed below:

-

Interdisciplinary meetings to discuss issues and problems eg access to services.

-

Oral health information leaflets to be given to clients on a 'need to' basis.

-

More oral health courses and that they be recognised for continued professional development.

-

Help with window displays during national public health campaigns.

-

Produce information relevant to the area the pharmacist is based in.

-

A list of key contacts to be used on an advisory basis.

A 'Pathways File' was suggested to meet most of the above criteria. A total of 70.6% of the pharmacists supported this idea and asked if they could take part in formulating one to meet the needs of their local area. A 'Pathways File' would be likely to take the format of flow diagrams to assess an end solution or relevant referral. There would be constant mailings of updates on courses, campaigns and their relevant contacts, leaflet distribution possibilities and sources and dates for regular interdisciplinary meetings. This file would have to be centrally co-ordinated by the PCT or Local Pharmacy Committee.

Discussion

There was an excellent rate of acceptance by the pharmacists asked to participate in this study. However, in the Durham Dales Primary Care Trust area there was a predominance in independently owned pharmacies and it is difficult to assess what impact this has on results compared to an equal independent/multiple distribution. The study only took place in a specific target area and therefore is not representative of other areas within the UK. Multiple pharmacies in the Durham Dales area tended to be co-located with the independents. There are 1,727 pharmacies owned by sole traders and 9,717 owned by multiples nationally.10 Therefore nationally, only 18% of pharmacies are independent whereas in the Durham Dales it is 78%. Nationally the number of independent pharmacies is decreasing steadily.

The Durham Dales has 210 pharmacies per million people which is higher than seven out of the 10 PCTs which make up the County Durham and Tees Valley Strategic Health Authority.10 This is due to the rural nature of the area compared to the other more urban PCTs.

The number of people requesting general health advice per week was most commonly over 100. The amount of requests on oral health advice was usually over 11. However overall, people do not use the pharmacy at present for oral health advice as frequently as they may for their general health as seen in the results acquired.

The most common oral health complaints were ones of ulcers and toothache/pain relief. The recommendations given to these patients were to visit a dentist and they were supplied with short-term pain relief. The PCT has identified access problems for unregistered patients and consequently they are unable to obtain resolution of acute problems.4 It is also significant to note that although the most common recommendation of the pharmacist is 'to see a dentist', few pharmacists had ever met the staff at their local dental practice, didn't know the opening times of the practice or indeed even the emergency arrangements. To most clients 'to see a dentist' is not an immediate or even short-term option; 23.5% of pharmacists would advise to see a doctor. At the present time, management of acute conditions requires a prescription from a dentist or doctor. However, this can be a waste of a doctor's time and is of little long-term help to the patient. In the 'new pharmacy contracts' and 'patient group directives' pharmacists could assess and dispense emergency medications when necessary until a dental appointment can be acquired and thereby reducing the misuse of resources of the general medical practitioner.11 It should be noted that the above results were behaviour patterns reported by the pharmacists and not based on individual patient questionnaires.

Nearly 71% of pharmacists said they were confident giving oral healthcare advice. There were 52.9% who said they based their recommendations on oral health training they had received on courses. A total of 65% expressed an interest in developing their oral healthcare knowledge further through attendance on more courses or accessible programmes. This demonstrates that pharmacists are an underused but potentially viable oral healthcare resource. If the investment is put into their training then they can reasonably be expected to undertake more responsibilities as oral healthcare providers. This would meet the desired objectives of the Wanless Report, which expresses a need to re-assess what work could be undertaken by pharmacists.2 Important flaws in the oral healthcare knowledge of pharmacists has previously been shown in other studies and our research is consistent with other studies which show that pharmacists want to take a more active approach to health promotion.6,12 Of the pharmacists in this study, 82.4% have advised that they wish to participate in oral health promotional activities. There is a need to support these pharmacies in this respect, especially during national campaigns.13 The support that has been requested by the pharmacies is not financially demanding, such as relevant oral health leaflets and window displays. Ghalamkari et al.14 reported the benefits of proactive pharmacies who have been provided with relevant training and support. This study reiterates that proactive pharmacists and pharmacy environments are conducive to clients wanting to seek advice.

Our research showed that the stocks of oral healthcare products in pharmacies were relatively low compared to larger city retailers. Multiples carried a larger stock of each item and three extras not found in the independents. An increased level of oral healthcare knowledge, participation in local and national oral health campaigns and greater diagnostic responsibility should boost requirements for oral healthcare products thereby increasing range of stocks which would benefit the patients as well as the pharmacist.

For many years there have been schemes in the USA whereby pharmacists devote a section of their store as an oral health centre where they have been specially trained to provide a basic but comprehensive oral healthcare advisory service.15 Pharmacists have been reported as the second most used source of advice on general health matters and therefore can and should also be used in an oral health capacity.14 Patients have specified the main reasons for using pharmacists for advice were that there was then 'no need to bother the doctor' and they had not 'needed an appointment' to see the pharmacist. There is no reason why this may not apply to dentists too.

Hidden sugars in baby foods and juices, liquid medicines, lozenges and cough sweets, all of which are commonly sold in community pharmacies, can with continuous usage, cause severe damage to the dentition. Therefore pharmacists are suitably placed to advise clients on their detrimental effects and the sugar-free alternatives. A pharmacist trained in oral health can advise the public on the most appropriate choices of dental products and the use of fluoride supplements. Pharmacists also have the potential for promoting products such as dental floss and mouthwashes thereby improving periodontal health in the community. They can give advice on denture hygiene and encourage attendance at the dentist for oral screening — a commonly overlooked problem in the edentulous. A pharmacist's advice and early referral to a dentist can reduce the risk of malignancy progressing undetected. Recurrent ulcers are also often a marker for underlying systemic problems.

Pharmacists should also become part of the primary healthcare team and develop a relationship with their local dental practitioners, as at present their operating fields are very different.7,16 Our study has noted their requests to be part of interdisciplinary team meetings, to have key contacts to work with and to have a joint pathway of care to meet the needs of their local population. This would again provide a more efficient and comprehensive system to the benefit of both the client and all the primary healthcare team.

Barriers to health promotion in pharmacies that have been suggested previously can be overcome.17 Previous studies specify the barriers as being: (i) no liaison with other primary care team members, (ii) lack of space, (iii) lack of finance from health authority and (iv) lack of courses.

All these issues were raised in this study and possible solutions suggested, mostly by the pharmacists themselves. Multidisciplinary meetings would enable liaison with other primary care team members and even more importantly this can be done on a local basis to meet the needs of the local clientele. Lack of space is not necessarily a problem as pharmacist shops all have window space which they would be prepared to have support in filling, especially with public health awareness material. Finance to pharmacists has now been brought down to a much more local level where the Primary Care Trust can highlight the health needs of the surrounding population. Therefore monies can be more efficiently directed (through pharmacies in some cases) to local areas of high need. Production of information leaflets and provision of more courses are not expensive but are useful options.

Conclusion

Pharmacists do already provide some degree of oral health advice in the Durham Dales area and they are keen to progress this knowledge further through courses and promotional activities. Patients use the pharmacies and regularly ask for their advice on both general and oral healthcare. There are also current and future government initiatives to increase the capabilities and responsibilities of pharmacists to provide medications and treatments and also to take a more active and integrated role as part of a primary healthcare team. It is clear that they are presently an under-used service which is now getting the foundations to improve its general and oral healthcare provision. There is a definitive need of pharmacists for training and access to information on available dental services.

Recommendations

Proposals to the primary care trust to improve the oral healthcare provision by pharmacists would be:

-

Setting up of regular multidisciplinary and primary care team meetings.

-

Funding and provision of more continuing professional development (CPD) recognised oral health courses.

-

Funding for information leaflets, especially during national oral health campaigns.

-

A list of key contacts within the PCT to be provided to pharmacists ie, smoking cessation advisor, etc.

-

Support for window displays, especially to target problem health issues including oral health.

A 'pathways folder' to be used by the pharmacist. This would enable the pharmacists to follow the correct pathways and procedures agreed by all concerned at the local multidisciplinary meetings. They would however have to be validated by the primary care trusts to meet national standards.

References

Department of Health. Group Patient Directives. London: Department of Health, April 2000.

Wanless D . Securing our future health: Taking a long-term view. Final Report. Department of Health, April 2002.

Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. A vision for pharmacy in the new NHS. Consultation Paper, July 2003.

www.countryside.gov.uk. Rural Services Survey 2001.

www.statistics.gov.uk. Census 2001-Population Report.

Chestnutt IG, Taylor MM, Mallinson EJM . The provision of dental and oral health advice by community pharmacists. Br Dent J 1998; 11: 532–534.

Anderson C . Promoting oral health: nurses and pharmacists working together. Br J Comm Nurs 1998; 3: 41–44.

Sheridan J, Aggleton M, Carson T . Dental health and access to dental treatment: a comparison of drug users and non-drug users attending community pharmacies. Br Dent J 2001; 19: 453–457.

Department of Health. Building on the best choice responsiveness and equity in the NHS. Publication No.35. Department of Health: London, Dec 2003.

Keene JM, Cervetto S . Health promotion in community pharmacy: a qualitative study. Health Eco J 1995; 54: 285–293.

Ghalamkari HH, Rees J, Saltrese-Taylor A, Ramsden M . Evaluation of pilot health promotion project in pharmacies: (1) Quantifying the pharmacists' health promotion role. Pharm J 1997; 258: 38–143.

Ghalamkari HH, Rees J, Saltrese-Taylor A, Ramsden M . Evaluation of pilot health promotion project in pharmacies: (2) Clients' initial views on pharmacists advice. Pharm J 1997; 258: 314–317.

McGregor T . The Pharmacist and Oral Health. J Am Pharm Assoc 1973; 13: 238–243.

McGregor T . Oral Health Education for Pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc 1975; 15: 74–76.

Moore S, Cairns C, Harding G, Craft M . Health promotion in the high street: a study of community pharmacy. Health Econ J 1995; 54: 275–284.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs D. Metcalfe, pharmacy Professional Excutive Committee member of the Durham Dales PCT for her advice in undertaking this study and to all the pharmacists who gave their time to complete and discuss the questionnaires.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maunder, P., Landes, D. An evaluation of the role played by community pharmacies in oral healthcare situated in a primary care trust in the north of England. Br Dent J 199, 219–223 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812614

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812614

This article is cited by

-

Fostering relationships

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

A critical synthesis of the role of the pharmacist in oral healthcare and management of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

BDJ Open (2020)

-

Relationships between dental personnel and non-dental primary health care providers in rural and remote Queensland, Australia: dental perspectives

BMC Oral Health (2017)

-

The relationship of primary care providers to dental practitioners in rural and remote Australia

BMC Health Services Research (2017)

-

Oral health promotion in the community pharmacy: an evaluation of a pilot oral health promotion intervention

British Dental Journal (2017)