Abstract

Study design:

Retrospective cross-sectional study with anonymous postal data collection.

Objective:

Regaining the best possible mobility and independence is not only the focus of the rehabilitation process for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI), but also represents an important criterion for the individual's quality of life (QoL). Therefore, if and to what extent physical exercise (PE) influences the QoL of individuals with SCI was investigated.

Setting:

The period of investigation extended from September 2007 to January 2008. Data were acquired from the BG Trauma Hospital Hamburg database and the German Wheelchair Sport Federation databases.

Methods:

Analysis of 277 questionnaires of individuals with acquired SCI between the age of 16 and 65 years with complete wheelchair dependency in everyday life and lesion level lower C5.

Results:

In all, 51.5% of all individuals were reported being actively involved in sports as opposed to 48.5% individuals not participating in sports. Individuals actively involved in sports have higher employment rate than physically inactive individuals with SCI. PE was identified as the main influencing determinant of QoL. This was particularly within the physical and psychological dimensions.

Conclusion:

In discovering the potential of individuals with SCI for getting involved in PE, the improvement of physical and coordinative skills with interaction between individuals with SCI and external sport groups should be an inherent part of the rehabilitation process. Individuals not having access to PE should be given the opportunity to participate in wheelchair mobility courses. This may improve the adherence to PE of individuals with SCI in post-clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A spinal cord injury (SCI) brings along physical, psychological and social changes in all areas of everyday life for the affected individual. Regaining the best possible mobility and independence is, thus, not only the focus of the rehabilitation process of individuals with SCI, but also represents an important criterion for the individual's quality of life (QoL). The assessment of rehabilitation success, therefore, should not only involve biological and physical parameters but also QoL, and should be evaluated by the person affected.1

There is no universally accepted definition of QoL. QoL is a person-oriented outcome parameter and a multi-dimensional construct, which considers the subjective evaluation of objective living conditions in different areas of life.2, 3 Some researchers prefer to emphasize the interest in health aspects, so they use the term ‘Health related Quality of Life’, which is still a loose definition.4 In this paper, we use the generally accepted term ‘QoL’. In the international literature, a constantly growing research interest in the area of QoL topics has been apparent in recent years.5, 6

In the past, several studies have shown an overall satisfying QoL after the rehabilitation process experienced by individuals with SCI.7, 8, 9, 10 This has been attributed to the coping and adaptation processes experienced by the individuals to adapt to their new life situation. Fuhrer et al.,11 however, state that QoL in individuals with SCI is lower when compared with QoL values in the general population.11

As a result of paralysis, QoL primarily is affected by functional impairments (that is, inability to walk, spontaneous urine loss, incontinence and pain). Different studies demonstrated that QoL is greatly independent from the spinal level at which the cord injury occurred, the degree of the general injury and the impairment level.8, 9, 10, 11 Parameters such as age, vocational perspective, as well as psychological and social aspects have been shown to have a great influence on QoL.12, 13 Hess et al.14 assume that, apart from financial reasons, employment has a positive effect on the psyche and subjective well-being of individuals with acquired SCI.14

Physical exercise (PE) represents an important therapeutic part of successful mobility advancement and contributes greatly to a rehabilitation process aiming at self-determination and autonomy.15 Therefore, it also has a great impact on QoL.13 Little is known in Germany whether PE and sport exert a positive influence on different aspects of the QoL of individuals with SCI. Hence, this study investigated whether and to what extent PE and sport influences the physical, psychological, social and context-related QoL of individuals with SCI with complete wheelchair dependency in everyday life. The results should lead to recommendations for improving the process of rehabilitation of individuals with SCI in the clinical and post-clinical setting.

Methods

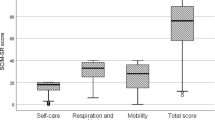

Data collection of the cross-sectional study was based on a questionnaire. As no suitable standardized instrument for the examination of PE and sport as well as socio-demographic data for wheelchair-dependent individuals with SCI existed, all 54 questions were specifically developed and designed by experts (medical science, sports science, social sciences and two individuals with SCI) for our investigation. QoL was recorded according to the short version of the generic questionnaire QoL-Feedback from Hanssen-Doose and Schüle,16 which addresses 42 items in four main domains: (1) physical field, (2) social field, (3) psychological field and (4) context field.16 The 42 questions of the QoL-Feedback were integrated in the entire questionnaire. The instrument, available in German, was calibrated using individuals without chronic diseases and patients with type 2 diabetes. Cronbach α as measurement of the internal consistency was α=0.92 in the physical field, α=0.85 in the social field, α=0.87 in the psychological field and α=0.70 in the context field. The test of convergent validity of the ‘QOL-Feedback’ showed high correlations with corresponding subscales of a frequently applied generic instrument SF-36.16 The QOL-Feedback instrument is suitable for wheelchair-dependent individuals and avoids problems identified in the use of the SF-36 in the physical function domain. Therefore, the SF-36 is less useful to investigate differences in the group of individuals with SCI.17

Table 1 describes the specification of the underlying construct measured by the QoL-Feedback. Statistical analysis was carried out by SPSS 17.0. Calculations included frequencies, mean values and comparing mean values (unpaired t-test, variance analysis), correlation to identify strength and direction of the relationship between variables and discriminant analysis to identify predictors. A total of 1363 individuals with acquired SCI from 16 to 65 years of age and a lesion level lower C5 were contacted by postal mail. This included 918 patients who had been treated at the SCI Centre of the BG Trauma Hospital between January 1997 and July 2007 (first treatments or re-admissions), and 445 individuals listed in the national database of the German Wheelchair Sport Federation. The investigation period extended from September 2007 until January 2008. Owing to the anonymous form of collecting data with self-answered questionnaires, classification according to the International Standards for the Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury could not be applied. In all, 457 of the 1363 individuals returned the questionnaires (return rate of 34%). From this group, partially or fully ambulant individuals (n=88), postal returns (n=38), invalid questionnaires (n=20), individuals older than 65 years (n=11), deceased individuals (n=10), individuals with a lesion level above C5 (n=8) and other kinds of disabilities (n=5) were excluded. Thus, the available net sample was n=277.

Results

The sample group had a mean age of 41.8 years (s.d.=12.7) with 79% male and 21% female. In all, 78.3% of the individuals were living with paraplegia compared with 21.7% individuals living with tetraplegia. The relation of complete to incomplete lesion was 62.9–37.1%. In 79% of all cases, the injury was caused by an accident (21% disease/other) and in almost 50%, the SCI occurred more than 5 years previously. In all, 15.4% of all individuals with SCI were employed full-time, 13.9% part-time and 6.2% were in a casual paid position or worked irregularly. Overall, 59% were unemployed. This is in contrast to the vocational situation before the SCI when almost three-quarters of the individuals (74.2%) had either a full-time or part-time employment, or worked in casually paid positions or irregularly (see Figure 1). The unemployment rate of individuals with SCI caused by accident on the job (n=57, 20.6%) is about 10% higher (not significant) compared with the unemployment rate of the rest of the sample group (67.9 vs 56.7%).

Physical exercise and sport

In all, 51.5% of all individuals reported being actively involved in sports, compared with 48.5% individuals with SCI not participating in sports. Of the physically active individuals, 83.2% engaged in recreational exercises and sports. The most frequent sport was handbiking (51.1%). Health-enhancing exercises were favoured by more than half of all individuals (54.6%), whereby 37.6% preferred fitness/resistance training and 17% chose gymnastics. Fitness, fun and health were named as the main incentives for exercising. No differences could be identified between individuals with paraplegia and tetraplegia.

A closer examination of the active individuals showed that this subgroup was more frequently employed than individuals not involved in sports (P=0.007, Figure 2). The data also showed that individuals with paraplegia were more frequently involved in sports than people with tetraplegia (P=0.029, Figure 2). No statistically significant differences were identified concerning PE and sport for individuals with high and low-level paraplegia. Individuals who were actively involved in sports before SCI occurred (66.2% active to 33.8% inactive) were significantly more active in sports after SCI (P=0.007).

Quality of life

The four domains, as well as all single QoL scales of the QOL-Feedback are reported in Table 2. The scale ranges from 1 (low QoL) to 5 (high QoL). Although the mean values of the ‘social’ and ‘context’ field rank at the same level as those of the comparison group without disability, the QOL-domains ‘physical’ and ‘psychological’ exhibited considerably lower values. Especially in the single QOL scales, ‘physical capacity in everyday life’, ‘mobility’, ‘sleep’, ‘pain’, ‘coping’, ‘nature and environment’ and ‘housing’ led to diverging ranking results.

Predictors of QoL in individuals with SCI

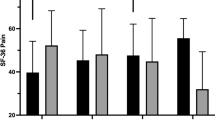

The identification of QoL predictors was accomplished using a discriminant analysis. Results showed that QoL is not affected by gender, age and time of incidence of SCI. Moreover, no statistically significant differences between complete and incomplete SCI, as well as between disease and accident caused SCI were observed. The physical dimension of QoL was affected by the lesion level, employment, wheelchair mobility (The classification of wheelchair mobility into good, average and poor is geared to a rating of three experts in wheelchair mobility and wheelchair training. These requirement defaults were set in relation to the self-information data of the interviewed individuals.) and the involvement in PE (see Figure 3). Individuals, who were employed, had good to average wheelchair mobility, engaged in sports or lived in a community state, had a higher social QoL (see Figure 4). From a psychological view, individuals, who were wheelchair-mobile and involved in sports, reported higher QoL values than less mobile and physically inactive individuals (see Figure 5). In the context domain of QoL, differences were noted according to physical exercise and life situation (see Figure 6).

Quality of life and physical exercise

A more detailed analysis of the influence of PE on QoL showed a correlation in all four domains of QoL, especially within the domain of physical and psychological QoL (see Figure 7). In order to avoid confusing the results of the QoL through the possible interaction of PE and influencing factors like employment, lesion level, life situation and wheelchair mobility, a univariate analysis of variance was carried out. The results showed positive effects of PE for female and male individuals with SCI in all four domains of QoL, independent of possible fogging factors.

Analysis of the single quality of life scales

Within the sample group, several largely diverging ranks for the single QoL scales were noted between the physically active individuals with SCI and physically inactive individuals. The most prominent differences (P<0.001) occurred in the single scales of physical domain ‘physical capacity in everyday life’, ‘physical activity’ and ‘mobility’ as well as in the single scales of psychological domain ‘remedial exercises’, ‘energy’ and ‘self-confidence’. Differences were also identified for the single scales of the social dimension of QoL ‘leisure time’ (P=0.003) and the single scale of the context-referred domain ‘nature’ (P=0.001). Still significant, albeit less prominent, differences were seen at the single scale for the physical domain ‘sleep’ (P=0.030) and for the single scale of the social domain ‘work’ (P=0.019) (see Table 3).

Discussion

Individuals with acquired SCI being actively involved in PE and sports differ from physically inactive individuals. They report a comparatively better QoL within physical, psychological, social and context field. The results support the findings in other studies focussing on various effects of PE and sport on individuals with SCI.13, 15, 18, 19 Both the functional effects such as the increase of physical resistance, mobility and coordination, as well as social and psychological effects such as an increase in self-confidence, self concept or mental state were identified. Our study confirmed that these findings also apply to individuals with acquired SCI in Germany. The stratification of the interviewed individuals into ‘actively involved in physical exercise’ and ‘physically inactive’ demonstrated differences in the single scales that are directly correlated with the existence of PE. Owing to the QoL construct used in our study, this was to be expected. It can be assumed that the differences within the single scale ‘physical capacity in everyday life’ and ‘mobility’ are possibly due directly to the effects of PE. The difference of the scale ‘sleep’ within the social QoL can also be attributed to the effect of PE, which improves drowsiness and sleep behaviour.18 These beneficial effects of PE on the QoL in individuals with SCI should be considered even more positively, as these effects are, in general, the areas which achieve low QoL values in the population of SCI when compared with a healthy group.11, 12, 14 The scale ‘pain’ which has also been identified as a considerably differing parameter between affected and healthy individuals and as an important QoL factor for individuals with SCI, was not improved significantly by PE in this study. Considering the findings of Hicks et al.,19 who determined significant increases in the physical and psychological well-being of 21 individuals in a 9-month study with 2 Units of ergometer training per week,19 this supports the recommendation of health-related PE, such as handbiking, to reduce the pain in SCI.

In the study, the different values stated by physically active and physically inactive individuals in the single scales of the psychological dimension of QoL ‘energy ‘and ‘self-confidence’ are striking. In accordance with the findings in healthy individuals, they indicate the positive effects of PE and sports on the individual psychophysical balance. The differences in the single scale ‘nature’ are explicable as many sports, especially the aforementioned handbiking, which are performed in natural environments. The differences within the range ‘work’ reflect positive effects of exercising on the vocational life. The positive effects of employment on the individual's QoL can be strengthened by PE, which improves physical capacity as well as self-confidence and energy.12, 14 The assumption that a good financial situation or a better health care result in a higher QoL of individuals involved in sports could not be confirmed. In our study, PE and sport was identified as the main influencing determinant of QoL particularly within the physical and psychological dimension. In general, the results support the findings,13, 15, 19 that positive effects of PE are an important parameter for QoL of individuals with acquired SCI.

Study limitations

Given the cross-sectional nature of the results, the interpretation of the impact of PE and sport on the QoL is restricted. Future research with a longitudinal approach would be valuable in this area and has already been initiated by the authors. Secondly, owing to the protection of privacy, it was not possible to remind the individuals to respond to the postal survey or control the return rate of questionnaires. This might have led to the low return rate and a possible data bias. But comparing the data of our included individuals with representative data in Germany the results are comparable.20

Conclusion

Under the concepts of prevention and lifelong rehabilitation, the results lead to the conclusion that PE and sports must be integrated as early as possible into the rehabilitation process. Owing to the constant shortening of the rehabilitation duration for individuals with SCI in Germany, the time to introduce and accustom patients to specific and wheelchair adapted sports is very limited. However, because of our findings, the improvement of physical and coordinative skills for discovering the potential of individuals with SCI for getting involved in PE is essential. Also, the interaction between the individuals with SCI and external sport groups must be an inherent part of the rehabilitation process. This may improve the adherence to PE of individuals with SCI in post-clinical settings. A pre-condition, for the participation of individuals with SCI in PE programmes in the hospital or in the post-clinical setting as well as in self-organized PE, is the early instalment of wheelchair mobility training because successful wheelchair handling increases the individual's self-confidence and motivation to meet new challenges in the wide range of PE. Individuals who, despite all efforts, do not gain access to PE programs, should be given the opportunity to participate in wheelchair mobility courses. Skills instilled and acquired in these courses are necessary for a better everyday life management and can thereby provide an important contribution to the QoL.15

Further research should investigate, in a longitudinal study design, the question how and to what extent well-developed wheelchair mobility affects PE and QoL of wheelchair-dependent individuals with SCI. Furthermore, it has to be clarified whether it is possible to integrate programs in the life long after care of SCI to initiate outlasting PE.

References

Levine S . The meanings of health, illness, and quality of life. In: Guggenmoos-Holzmann I, Bloomfield K, Brenner H, Flick U (eds). Quality of Life and Health. Concepts, Methods and Applications. Blackwell: Berlin, 1995 pp 7–16.

Fuhrer MJ . Subjectifying quality of life as a medical rehabilitation outcome. Disabil Rehabil 2000; 22: 481–489.

Joyce CRB, McGee HM, O’Boyle C (ed). Individual quality of life: approaches to conceptualisation and assessment. Harwood: Amsterdam, 1999, pp 3–9.

Fayers PM, Machin D . Quality of Life. The assessment, analysis, and interpretation of patient oriented outcomes. 2nd edn. Wiley: West Sussex, 2000, p 4.

Kind P . Measuring quality of life in evaluating clinical interventions: an over-view. Ann Med 2001; 33: 323–327.

Brenner MH . Quality of life assessment in medicine: A historical view of basicscience and applications. In: Guggenmoos-Holzmann I, Bloomfield K, Brenner H, Flick U (eds). Quality of Life and Health. Concepts, Methods and Applications. Blackwell: Berlin, 1995, pp 41–57.

Schönherr MC, Groothoff JW, Mulder GA, Eisma WH . Participation and satisfaction after spinal cord injury: results of a vocational and leisure outcome study. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 241–248.

De Vivo MJ, Richards JS . Community reintegration and quality of life following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 108–112.

Eisenberg MG, Saltz CC . Quality of life among aging spinal cord injures persons: long term rehabilitation outcomes. Paraplegia 1991; 29: 514–520.

Gerhart KA . Spinal cord injury outcomes in a population-based sample. J Trauma 1991; 31: 1529–1535.

Fuhrer MJ, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Clearman R, Young ME . Relationship of life satisfaction to impairment, disability, and handicap among persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Arch Phys Med 1992; 73: 552–557.

Evans RL, Hendricks RD, Connis RT, Haselkorn JK, Ries KR, Mennet TE . Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a literature critique and meta-analysis (1983–1992). J Am Paraplegia Soc 1993; 17: 60–66.

Tasiemski T, Kennedy P, Gardner BP, Tylor N . The association of sports and physical recreation with life satisfaction in a community sample of people with spinal cord injuries. Neurorehabilitation 2005; 20: 253–265.

Hess DW, Meade MA, Forchheimer M, Tate DG . Psychological well-being and intensity of employment in individuals with a spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2004; 9: 1–10.

Noreau L, Shephard RJ . Spinal cord injury, exercise and quality of life. Sports Med 1995; 20: 226–250.

Hanssen-Doose A, Schüle K . Development and validation of a generic QOL-instrument with an integrated physical activity component (QOL feedback). Qual Life Res 2006; 1 (Suppl.): A-132.

Haran MJ, King MT, Stockler MR, Marial O, Lee BB . Validity of the SF-36 Health Survey as an outcome measure for trials in people with spinal cord injury. CHERE Working Paper 2007/4, CHERE, Sydney 2007. Available at http://www.chere.uts.edu.au/pdf/wp2007_4.pdf.

Payne JK, Held J, Thorpe J, Shaw H . Effect of exercise on biomarkers, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in older woman with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008; 35: 635–642.

Hicks AL, Martin KA, Ditor DS, Latimer AE, Craven C, Bugaresti J, McCartney N . Long-term exercise training in persons with spinal cord injury: effects on strength, arm ergometry performance and psychological well-being. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 34–43.

Exner G . Querschnittlähmungen. In: BAR Rehabilitation und Teilhabe; Ärzte Verlag: Köln 2005, pp 197–203.

Acknowledgements

The investigation is part of the project ‘Participation Through Mobility For Individuals With SCI’ sponsored by the German Statutory Accident Insurance (DGUV) and was realized in close cooperation with Peter Richarz from the German Wheelchair Sports Federation (DRS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anneken, V., Hanssen-Doose, A., Hirschfeld, S. et al. Influence of physical exercise on quality of life in individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 48, 393–399 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.137

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.137

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Questionnaire of inclusion in Paralympic dance: validation and pilot study

Sport Sciences for Health (2022)

-

Quality of life, concern of falling and satisfaction of the sit-ski aid in sit-skiers with spinal cord injury: observational study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)

-

Is Fitbit Charge 2 a feasible instrument to monitor daily physical activity and handbike training in persons with spinal cord injury? A pilot study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2018)

-

Leisure time physical activity participation in individuals with spinal cord injury in Malaysia: barriers to exercise

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

Leisure time physical activity among older adults with long-term spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2017)