Abstract

Increasing life expectancy in industrialized societies has resulted in a huge population of older adults with cardiovascular disease. Despite advances in device therapy and surgery, the mainstay of treatment for these disorders remains pharmacological. Hypertension affects two-thirds of older adults and remains a potent risk factor for coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and stroke in this age group. Numerous trials have demonstrated reduction in these adverse outcomes with antihypertensive drugs. After acute myocardial infarction, β-adrenergic blockers reduce mortality regardless of patient age. Statins and antiplatelet drugs have proven beneficial in both primary and, especially, secondary prevention of coronary events in older adults. In elders with chronic heart failure, loop diuretics must be used cautiously, owing to their higher potential for adverse effects, whereas angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and β-blockers reduce symptoms and prolong survival. The high risk of stroke in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation is markedly reduced with warfarin, although bleeding risk is increased. The high prevalence of polypharmacy among older adults with cardiovascular disease, coupled with age-associated physiological changes and comorbidities, provides major challenges in adherence and avoidance of drug-related adverse events.

Key Points

-

Aging of the population, coupled with the dramatic age-related increase in cardiovascular disease, has resulted in a huge number of elderly patients requiring chronic medical therapy for these disorders

-

Age-related changes in physiology and body composition result in altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics that often require drug dosing adjustments in elderly adults

-

Polypharmacy and age-related comorbidities increase the risk of adverse drug– drug and drug–disease interactions among elderly patients

-

Clinical trials have shown that antihypertensive agents, statins, antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants, β-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, and aldosterone antagonists benefit elderly patients with cardiovascular disease

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Day, J. C. Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050. Current Population Reports Series (US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1996).

Thom, T. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 113, e85–e151 (2006).

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Fact Book: Fiscal Year 2009 [online], (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, 2009).

Mangoni, A. A. & Jackson, S. H. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57, 6–14 (2004).

Hui, K. K. in Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics (eds Singh, B. N., Dzau, V. J., Woosley, R. L. & Vanhoutte, P. M.) 1127–1136 (Churchill-Livingstone, New York, 1993).

Fleg, J. L. & Lakatta, E. G. in Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly 4th edn (Eds Aronow, W. S., Fleg, J. L. & Rich, M. W.) 1–43 (Informa, New York, 2008).

Cody, R. J., Torre, S., Clark, M. & Pondolfino, K. Age-related hemodynamic, renal, and hormonal differences among patients with congestive heart failure. Arch. Intern. Med. 149, 1023–1028 (1989).

Jyrkka, J., Vartiainen, L., Hartikainen, S., Sulkava, R. & Enlund, H. Increasing use of medicines in elderly persons: a five-year follow-up of the Kuopio 75+ Study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 62, 151–158 (2006).

Goldberg, R. M., Mabee, J., Chan, L. & Wong, S. Drug–drug and drug–disease interactions in the ED: analysis of a high-risk population. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 14, 447–450 (1996).

Bressler, R. in Geriatric Pharmacology (Eds Bressler, R. & Katz, M. S.) 54–66 (McGraw Hill, New York, 1993).

Parker, B. M. & Cusack, B. J. in Geriatrics Review Syllabus: A Core Curriculum in Geriatric Medicine 3rd edn (Eds Reuben, D. B., Yoshikawa, T. T. & Besdine, R. W.) 33–40 (Kendall Hunt Publishers, Dubuque, 1996).

Reschovsky, J. D. & Felland, L. E. Access to prescription drugs for Medicare beneficiaries. Track. Rep. 23, 1–4 (2009).

MacLaughlin, E. J. et al. Assessing medication adherence in the elderly: which tools to use in clinical practice? Drugs Aging 22, 231–255 (2005).

Balkrishnan, R. Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly. Clin. Ther. 20, 764–771 (1998).

Salazar, J. A., Poon, I. & Nair, M. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly: expect the unexpected, think the unthinkable. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 6, 695–704 (2007).

Cutler, J. A. et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hypertension 52, 818–827 (2008).

Vokonas, P. S., Kannel, W. B. & Cupples, L. A. Epidemiology and risk of hypertension in the elderly: the Framingham Study. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 6, s3–s9 (1988).

Shekelle, R. B., Ostfeld, A. M. & Klawans, H. L. Jr. Hypertension and risk of stroke in an elderly population. Stroke 5, 71–75 (1974).

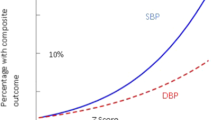

Lewington, S., Clarke, R., Qizilbash, N., Peto, R. & Collins, R. for the Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data from one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 360, 1903–1913 (2002).

Rich, M. W. in ACC Self Assessment Program Syllabus Version 6. 20.16–2025 (ACC Foundation, Bethesda, 2005).

Beckett, N. S. et al. for the HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1887–1898 (2008).

Chobanian, A. V. et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High blood Pressure. The JNC 7 report. JAMA 289, 2560–2572 (2003).

Mancia, G. et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J. Hypertens. 27, 2121–2158 (2009).

Law, M. R., Morris, J. K. & Wald, N. J. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiologic studies. BMJ 338, b1665 (2009).

Jamerson, K. et al. for the ACCOMPLISH Trial Investigators. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2417–2428 (2008).

Amery, A. et al. Mortality and morbidity results from the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly trial. Lancet 1, 1349–1354 (1985).

SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 265, 3255–3264 (1991).

The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs. diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 288, 2981–2997 (2002).

MRC Working Party. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ 304, 405–412 (1992).

Dahlöf, B. et al. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension). Lancet 338, 1281–1285 (1991).

Hansson, L. et al. Randomized trial of old and new antihypertensive drugs in elderly patients: cardiovascular mortality and morbidity the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 Study. Lancet 354, 1751–1756 (1999).

Dahlöf, B. et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 359, 995–1003 (2002).

Messerli, F. H., Grossman, E. & Goldbourt, U. Are beta blockers efficacious as first line therapy for hypertension in the elderly? A systematic review. JAMA 279, 1903–1907 (1998).

William, B. et al. Differential impact of blood pressure lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFÉ) study. Circulation 113, 1213–1225 (2006).

Staessen, J. A. et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet 350, 757–764 (1997).

Wang, J. G., Staessen, J. A., Gong, L. & Liu, L. Chinese trial on isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China) Collaborative Group. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 211–220 (2000).

Gong, L. et al. Shanghai trial of nifedipine in the elderly (STONE). J. Hypertens. 14, 1237–1245 (1996).

Pepine, C. J. et al. for the INVEST Investigators. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST). A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290, 2805–2816 (2003).

Wing, L. M. et al. for the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study Group. A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 583–592 (2003).

Yusuf, S. et al. Effects of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high risk patients: the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 145–153 (2000).

Dahlof, B., Pennert, K. & Hansson, L. Reversal of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients. A meta-analysis of 109 treatment studies. Am. J. Hypertens. 5, 95–110 (1992).

Yusuf, S. et al. for the ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1547–1559 (2008).

Julius, S. et al. for the VALUE trial group. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet 363, 2022–2031 (2004).

Lindholm, L. H. et al. for the LIFE Study Group. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes in the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study (LIFE): a randomized trial against atenolol. Lancet 359, 1004–1010 (2002).

ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 283, 1967–1975 (2000).

Frishman, W. H., Aronow, W. S. & Cheng-Lai, A. in Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly 4th edn (Eds Aronow, W. S., Fleg, J. L. & Rich, M. W.) 99–135 (Informa Healthcare, New York, 2008).

Duprez, D. A., Munger, M. A., Botha, J., Keefe, D. L. & Charney, A. N. Aliskiren for geriatric lowering of systolic hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J. Hum. Hypertens. 24, 600–608 (2010).

Manolio, T. et al. Cholesterol and heart disease in older persons and women. Review of an NHLBI workshop. Ann. Epidemiol. 2, 161–176 (1992).

Grundy, S. M. et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation 110, 227–239 (2004).

Ridker, P. M. et al. for the JUPITER Study Group. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 2195–2207 (2008).

Downs, J. R. et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels. Results of AFCAPS/ TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Preention Study. JAMA 279, 1615–1622 (1998).

Neil, H. A. et al. for the CARDS Study Investigators. Analysis of efficacy and safety in patients 65–75 years at randomization: Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS). Diabetes Care 29, 2378–2384 (2006).

Shepherd, J. et al. for the PROSPER study group. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 360, 1623–1630 (2002).

Miettinen, T. A. et al. Cholesterol-lowering therapy in women and elderly patients with myocardial infarction or angina pectoris: findings from the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Circulation 96, 4211–4218 (1997).

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 360, 7–22 (2002).

Lewis, S. J. et al. Effect of pravastatin on cardiovascular events in older patients with myocardial infarction and cholesterol levels in the average range. Results of the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 129, 681–689 (1998).

Hunt, D. et al. Benefits of pravastatin on cardiovascular events and mortality in older patients with coronary heart disease are equal to or exceed those seen in younger patients: results from the LIPID trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 134, 931–940 (2001).

Wenger, N. K., Lewis, S. J., Herrington, D. M., Bittner, V. & Welty, F. K. for the Treating to New Targets. Study Steering Committee and Investigators. Outcomes of using high- or low-dose atorvastatin in patients 65 years of age or older with stable coronary heart disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 147, 1–9 (2007).

Deedwania, P. et al. Effects of intensive versus moderate lipid-lowering therapy on myocardial ischemia in older patients with coronary heart disease: results of the Study Assessing Goals in the Elderly (SAGE). Circulation 115, 700–707 (2007).

Olsson, A. G., Schwartz, G. G., Szarek, M., Luo, D. & Jamieson, M. J. Effects of high-dose atorvastatin in patients > or =65 years of age with acute coronary syndrome (from the myocardial ischemia reduction with aggressive cholesterol lowering [MIRACL] study). Am. J. Cardiol. 99, 632–635 (2007).

Cannon, C. P. et al. for the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Comparison of intensive and moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1495–1504 (2004).

Baigent, C. et al. for the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomized trials of statins. Lancet 366, 1267–1278 (2005).

Alexander, K. P. et al. Management of hyperlipidemia in older adults. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 14, 49–58 (2009).

Cheng, J. W., Frishman, W. H. & Aronow, W. S. Updates on cytochrome P450-mediated cardiovascular drug interactions. Am. J. Ther. 16, 155–163 (2009).

Lipka, L. et al. for the Ezetimibe Study Group. Efficacy and safety of coadministration of ezetimibe and statins in elderly patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Drugs Aging 21, 1025–1032 (2004).

ClinicalTrials.gov. IMPROVE- IT. Examining outcomes in subjects with acute coronary syndrome: Vytorin (ezetimibe/simvastatin) vs simvastatin (Study PO4103) [online], (2010).

Rubin, H. B. et al. Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 410–418 (1999).

Keech, A. et al. for the FIELD study investigators. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9,795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 366, 1849–1861 (2005).

Ginsberg, H. N. et al. for the ACCORD Study Group. Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1563–1574 (2010).

Shek, A. & Ferrill, M. J. Statin–fibrate combination therapy. Ann. Pharmacother. 35, 908–917 (2001).

Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA 231, 360–381 (1975).

Villines, T. C. et al. The ARBITER 6-HALTS Trial (Arterial Biology for the Investigation of the Treatment Effects of Reducing Cholesterol 6-HDl and LDL Treatment Strategies in Atherosclerosis). Final results and the impact of of medication adherence, dose, and treatment duration. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 2721–2726 (2010).

ClinicalTrials.gov. AIM HIGH: Niacin plus Statin to Prevent Vascular Events [online], (2010).

ClinicalTrials.gov. Treatment of HDL to Reduce the Incidence of Vascular Events HPS2–THRIVE [online], (2010).

Peterson, E. D. & Alexander, K. P. in ACC Self Assessment Program Syllabus Version 6, 2034–2041 (ACC Foundation, Bethesda, 2005).

Alexander, K. P. et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part 1: non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation 115, 2549–2569 (2007).

Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy-1: prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ 308, 81–106 (1994).

Peters, R. J. et al. for the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) Trial Investigators. Effects of aspirin dose when used alone or in combination with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 108, 1682–1687 (2003).

Gantt, A. J. & Gantt, S. Comparison of enteric-coated aspirin and uncoated aspirin on bleeding time. Cathet. Cardiovasc. Diagn. 45, 396–399 (1998).

Yusuf, S. et al. for the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST segment elevation. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 494–502 (2001).

Wiviott, S. D. et al. for the TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2001–2015 (2007).

Frishman, W. H. & Sonnenblick, E. H. in Hurst's The Heart 9th edn (Eds Alexander, R. W. et al.) 1583–1618 (McGraw Hill, New York, 1997).

Hawkins, C. M., Richardson, D. W. & Vokonas, P. S. Effect of propranolol in reducing mortality in older myocardial infarction patients: the Beta Blocker Heart Attack Trial experience. Circulation 67, I94–I97 (1983).

Friedman, L. M. et al. Effect of propranolol in patients with myocardial infarction and ventricular arrhythmias. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 7, 1–8 (1986).

Gundersen, T., Abrahamsen, A. M., Kjekshus, J. & Rønnevik, P. K. Timolol-related reduction in mortality and reinfarction in patients aged 65–75 years surviving acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 66, 1179–1184 (1982).

Dargie, H. J. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet 357, 1385–1390 (2001).

Kennedy, H. L. et al. Beta-blocker therapy in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. CAST Investigators. Am. J. Cardiol. 74, 674–680 (1994).

Smith, S. C. Jr et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 113, 2363–2372 (2006).

Danahy, D. T. & Aronow, W. S. Hemodynamics and antianginal effects of high dose oral isosorbide dinitrate after chronic use. Circulation 56, 205–212 (1977).

Kloner, R. A. Pharmacology and drug interaction effects of the phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors: focus on α-blocker interactions. Am. J. Cardiol. 96 (12B), 42M–46M (2005).

The Multicenter Diltiazem Post Infarction Trial Research Group. Effect of diltiazem on mortality and reinfarction after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 319, 385–392 (1988).

Kelly, J. G. & O'Malley, K. Clinical pharmacokinetics of calcium antagonists. An update. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 22, 416–433 (1992).

Fox, K. M. for the EURopean trial On reduction of cardiac events with Perindopril in stable coronary Artery disease Investigators. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial (the EUROPA study). Lancet 362, 782–788 (2003).

Braunwald, E. et al. for the PEACE Trial Investigators. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 2058–2068 (2004).

Rich, M. W., Crager, M. & McKay, C. R. Safety and efficacy of extended-release ranolazine in patients aged 70 years or older with chronic stable angina pectoris. Am. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 16, 216–221 (2007).

Tendera, M. III, Fox, K., Tardif, J. C. & Ford, I. Anti-ischemic and antianginal efficacy of ivabradine, a selective and specific If current inhibitor, in elderly patients with stable angina [abstract 3363]. Circulation 114, II_715 (2006).

Senni, M. et al. Congestive heart failure in the community: a study of all incident cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota in 1991. Circulation 98, 2282–2289 (1998).

MacIntyre, K. et al. Evidence of improving prognosis in heart failure: trends in case fatality in 66,547 patients hospitalized between 1986 and 1995. Circulation 102, 1126–1131 (2000).

Sica, D. A. & Gehr, T. W. Diuretic combinations in refractory edema states: pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic relationships. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 30, 229–249 (1996).

Sica, D. A. & Gehr, T. W. Drug absorption in congestive heart failure: loop diuretics. Congest. Heart Fail. 5, 37–43 (1998).

Page, J. & Henry, D. Consumption of NSAIDs and the development of congestive heart failure in elderly patients: an under-recognized public health problem. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 777–784 (2000).

Baglin, A., Boulard, J. C., Hanslik, T. & Prinseau, J. Metabolic adverse reactions to diuretics. Clinical relevance to elderly patients. Drug Saf. 12, 161–167 (1995).

Neuberg, G. W. et al. for the PRAISE Investigators. Diuretic resistance predicts mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. Am. Heart J. 144, 31–38 (2002).

Pitt, B. et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 709–717 (1999).

ClinicalTrials.gov. A Comparison Of Outcomes In Patients In New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II Heart Failure When Treated With Eplerenone Or Placebo In Addition To Standard Heart Failure Medicines (EMPHASIS-HF) [online], (2010).

ClinicalTrials.gov. Aldosterone Antagonist Therapy for Adults With Heart Failure and Preserved Systolic Function (TOPCAT) [online], (2010).

Jessup, M. et al. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation 119, 1977–2016 (2009).

Pitt, B. et al. for the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1309–1321 (2003).

The Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 525–533 (1997).

Rich, M. W., McSherry, F., Williford, W. O. & Yusuf, S. for the Digitalis Investigation Group. Effect of age on mortality, hospitalizations, and response to digoxin in patients with heart failure: the DIG Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 38, 806–813 (2001).

Falch, D. The influence of kidney function, body size, and age on plasma concentration and urinary excretion of digoxin. Acta Med. Scand. 194, 251–256 (1973).

Slatton, M. L. et al. Does digoxin provide additional hemodynamic and autonomic benefit at higher doses in patients with mild to moderate heart failure and normal sinus rhythm? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 29, 1206–1213 (1997).

The CONSENSUS Study Group. Effect of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N. Engl. J. Med. 316, 1429–1435 (1987).

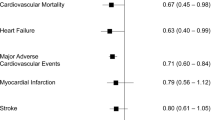

Flather, M. et al. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. ACE-Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Lancet 355, 1575–1581 (2000).

Packer, M. et al. Comparative effects of low and high doses of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril, on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure. Circulation 100, 2312–2318 (1999).

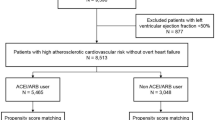

Pitt, B. et al. Randomised trial of losartan versus captopril in patients over 65 with heart failure (Evaluation of Losartan in the Elderly Study, ELITE). Lancet 349, 747–752 (1997).

Pitt, B. et al. Effect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial—The Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE II. Lancet 355, 1582–1587 (2000).

Cohn, J. & Tognoni, G. for the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1667–1675 (2001).

Granger, C. B. et al. for the CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet 362, 772–776 (2003).

CIBIS-II Investigators and Committees. The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet 353, 9–13 (1999).

MERIT-HF Study Group. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 353, 2001–2007 (1999).

Packer, M. et al. for the Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival Study Group. Effect of carvedilol on survival in chronic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1651–1658 (2001).

Flather, M. D. et al. for the SENIORS Investigators. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS). Eur. Heart J. 26, 215–225 (2005).

Mari, D. et al. Hemostasis and ageing. Immun. Ageing 5, 12 (2008).

Wolf, P. A., Abbott, R. D. & Kannel, W. B. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 22, 983–988 (1991).

Furberg, W. S. et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in elderly subjects (the Cardiovascular Health Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 74, 236–241 (1994).

Segal, J. B. et al. Prevention of threomboembolism in atrial fibrillation. A meta-analysis of trials of anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 15, 56–67 (2000).

The Sixty Plus Reinfarction Study Research Group. A double-blind trial to assess long-term anticoagulation therapy in elderly patients after myocardial infarction. Report of the Sixty Plus Reinfarction Study Research Group. Lancet 2, 989–994 (1980).

Shepherd, A. M., Hewick, D. S., Moreland, T. A. & Stevenson, I. H. Age as a determinant of sensitivity for warfarin. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 4, 315–320 (1977).

Singla, D. A. & Morrill, G. B. Warfarin doses in the very elderly. Am. J. Health. Syst. Pharm. 62, 1062–1066 (2005).

Hylek, E. M. & Singer, D. E. Risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in outpatient taking warfarin. Ann. Intern. Med. 120, 897–902 (1994).

Jacobs, L. G. & Billett, H. H. in Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly 4th edn (Eds Aronow, W. S., Fleg, J. L. & Rich, M. W.) 705–729 (Informa Healthcare, New York, 2008).

Blick, S. K., Orman, J. S., Wagstaff, A. G. & Scott, L. J. Fonaparinux sodium: a review of its use in the management of acute coronary syndromes. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 8, 113–125 (2008).

Gross, P. L. & Weitz, J. I. New antithrombotic drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 86, 139–146 (2009).

Chen, T. & Lam, S. Rivaroxaban. An oral direct factor Xa inhibitor for the prevention of thromboembolism. Cardiol. Rev. 17, 192–197 (2009).

Lassen, M. R. et al. for the ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomized double-blind trial. Lancet 375, 807–815 (2010).

Connelly, S. J. et al. for the RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigratran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1139–1151 (2009).

Krumholz, H. M. et al. Aspirin for secondary prevention after acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: prescribed use and outcome. Ann. Intern. Med. 124, 292–298 (1996).

Sobel, M. & Verhaeghe, R. Antithrombotic therapy for peripheral artery occlusive disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 133 (6 Suppl.), 815S–843S (2008).

Naseer, N. et al. Ticlopidine-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Heart Dis. 3, 221–223 (2001).

Nguyen, T., Frishman, W. H., Nawarskas, J. & Lerner, R. G. Variability of response to clopidogrel: possible mechanisms and clinical implications. Cardiol. Rev. 14, 136–142 (2006).

Connolly, S. et al. The ACTIVE Writing Group on behalf of the ACTIVE Investigators. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 367, 1903–1912 (2006).

Connolly, S. J. for the ACTIVE Investigators. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 2066–2078 (2009).

Fuster, V. et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation—executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 854–906 (2006).

Gage, B. F. et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for reducing stroke. Results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 285, 2864–2870 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Nina Hall (Program Analyst; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) and Joanne Pryor (Office Manager for W. H. Frishman; New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY, USA) in preparing this manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIH, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Government. Charles P. Vega, University of California, Irvine, CA, is the author of and is solely responsible for the content of the learning objectives, questions and answers of the MedscapeCME-accredited continuing medical education activity associated with this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. L. Fleg, W. S. Aronow, and W. H. Frishman researched data for the article, contributed to discussion of content, wrote and reviewed the manuscript before submission, and revised the article after peer-review and editing. The majority of reviewing and revising of the manuscript was done by J. L. Fleg.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J. L. Fleg is a stockholder/Director of Bristol-Myers Squibb. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fleg, J., Aronow, W. & Frishman, W. Cardiovascular drug therapy in the elderly: benefits and challenges. Nat Rev Cardiol 8, 13–28 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2010.162

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2010.162

This article is cited by

-

Nonagenarians admission and prognosis in a tertiary center intensive coronary care unit – a prospective study

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

-

Polypharmacy and severe potential drug-drug interactions among older adults with cardiovascular disease in the United States

BMC Geriatrics (2021)

-

Risk stratification and mortality prediction in octo- and nonagenarians with peripheral artery disease: a retrospective analysis

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2021)

-

COVID-19-associated cardiovascular morbidity in older adults: a position paper from the Italian Society of Cardiovascular Researches

GeroScience (2020)

-

Prognostic role of masked and white-coat hypertension: 10-Year mortality in treated elderly hypertensives

Journal of Human Hypertension (2019)