Abstract

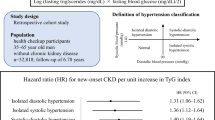

High blood pressure and elevated serum glucose levels often precede adverse cardiovascular events. The cardiovascular risk in otherwise healthy US adults with prehypertension (PreHTN) and/or prediabetes (PreDM), although perceived to be high, is largely undocumented. Coexisting PreHTN and PreDM in healthy US adults, correlates with untoward alterations in the commonly recognized cardiometabolic risk factors. The study investigated disease-free US adults (n=4,561) from the NHANES database (1999–2006). PreHTN and PreDM were diagnosed using JNC 7 and American Diabetes Association criteria, respectively; PreHTN was defined as systolic blood pressure 120–139 and/or diastolic blood pressure 80–89 mm Hg, and PreDM was defined as fasting blood sugar 100–125 mg dl−1. The prevalence of coexisting PreHTN and PreDM (Co-PreHTN+PreDM) during the study period (1999–2006) was 11.2±0.6%. Prevalence increased with age, was higher in men, and was lowest in non-Hispanic Blacks. The mean systolic blood pressure was 126.0±0.5 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure was 75.0±0.5 mm Hg and fasting blood sugar was106.3±0.3 mg dl−1. Compared to adults with normotension, normoglycemia, subjects with Co-PreHTN+PreDM displayed adversely altered cardiometabolic risk factors. Healthy men and women with Co-PreHTN+PreDM were, on average, overweight with a large waist circumference, displayed an exacerbated systemic inflammation and higher insulin resistance. They had elevated triglycerides, lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, leading to above average cardiac risk ratios and were significantly more likely to have two or three concomitant metabolic risk factors. High prevalence of Co-PreHTN+PreDM in healthy US adults, a strong correlate for dysregulated cardiometabolic risk factors, highlights a plausible accelerated pathway for early cardiovascular events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension1 and diabetes mellitus2, 3 are well recognized for escalating the risk for adverse cardiovascular events. The perceived potential for cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk enhancement by the clinical precursors: prehypertension (PreHTN) and prediabetes (PreDM), in healthy US adults, however, remains unsubstantiated. The probable CVD risk enhancement with PreHTN and PreDM, in some measure, is dependent upon the high risk for conversion from PreHTN to hypertension and from PreDM to diabetes. A very high proportion of men and women (37.3%) with blood pressure at the high end of the normal range in the Framingham cohort (JNC 6 criteria: blood pressure=130–139/85–89 mm Hg) developed hypertension within 4 years.4 A similar proportion of disease-free adults (38%) with PreHTN (JNC 7 criteria: blood pressure=120–139/80–89 mm Hg) in the Strong Heart Study progressed to hypertension within a 4-year period.5 A varying proportion of men and women (6–29%) with PreDM (American Diabetes Association criteria: impaired glucose tolerance indicated by 2 h serum glucose between 140–199 mg dl−1 after a 75 g oral glucose load) convert to diabetes mellitus within 4 years.6, 7, 8, 9

PreHTN and PreDM, however, also increase CVD risk because of their association with increased waist circumference (WC), high triglycerides (TGs), below-normal high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and either elevated blood pressure (PreHTN) or fasting blood glucose (PreDM). Each of these five risk factors, increased WC (>102 cm in men and >88 cm in women), elevated TG (>150 mg dl−1), low HDL-C (<40 mg dl−1 in men and <50 mg dl−1 in women), increased blood pressure (blood pressure >130/85 mm Hg) and elevated fasting blood glucose (100–125 mg dl−1), is individually associated with increased adverse cardiovascular events.10, 11, 12, 13 These factors increase CVD risk even more when any three (or more) of these five are used for the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.14

Given the persistent high prevalence of PreHTN15 and the progressively escalating prevalence of PreDM (unpublished observations), coupled with the high conversion rates of PreHTN to hypertension4, 5 and PreDM to diabetes,6, 7, 8, 9 instituting urgent preventive interventions is eminently desirable. We have demonstrated that PreHTN and PreDM are distinct clinical markers for an adverse cardiometabolic profile.15 In this study, we investigated the hypothesis that coexistent clinical PreHTN and PreDM are associated with an even more adverse cardiometabolic profile than either condition alone.

Methods

Source of data

Analyses were conducted using data from the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey collected from 1999 to 2006. NHANES uses a complex, multistage, probabilistic sampling design to select participants who are representative of the non-institutionalized, civilian US population. Sample weights assigned to each participant allow the development of good prevalence estimates for the US population. The National Center for Health Statistics ethics review board approved the original survey protocols. Informed consent was obtained from all NHANES participants. Trained personnel conducted home interviews for reliable data collection. This included demographic, socioeconomic, dietary and health-related information. A mobile exam center was used to obtain anthropometric measurements and secure a fasting blood draw. Medical personnel were utilized to obtain medical, dental and physiological measurements as well as results from the laboratory tests. Complete details can be accessed at the NHANES website.16

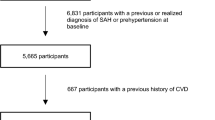

Exclusions

The 1999–2006 NHANES samples included 41 474 participants. A schematic of the exclusion criteria is shown in Figure 1. Participants under 20 years of age (21 163) were excluded, retaining 20 311 adults over 20 years of age. Other exclusions (15 750 excluded from 20 311) were as follows: pregnancy (1169); participation in only the interview portion (1253); lack of fasting blood glucose, body weight, body mass index (BMI) or WC measurements (10 164); lack of fasting weight (381); history of coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, angina, myocardial infarction, stroke or cancer (1421); treatment with blood pressure medication (866); and known diabetes mellitus (496). Thus, 36 913 of 41 474 participants did not meet the inclusion criteria, and the final sample size of disease-free healthy adults was 4561. There were 2423 men and 2138 women: 2206 non-Hispanic White, 835 non-Hispanic Black, 1,136 Mexican American and 384 other ethnicities. Their age distribution was as follows: 2152 ages 20–39; 1548 ages 40–59; 470 ages 60–69; and 391 ages 70+ years.

Data collection methods

Participants were required to come to a mobile examination clinic before 0900 hours after fasting for at least 9 h. If they arrived having fasted for less than 8.5 h, they received an analytical sampling weight equal to zero, as defined by the NHANES protocol. Blood was drawn from an antecubital vein of the left arm. Fasting plasma glucose was assessed by the hexokinase method. TGs, HDL-C, insulin and C reactive protein were also assayed from the fasting serum samples. Homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated to measure insulin resistance using the following formula: fasting serum insulin (μU ml−1) × fasting plasma glucose (mg dl−1)/405. Blood pressure was measured after the participant had rested quietly for 5 min. Three consecutive blood pressure readings were obtained. The average of these was recorded as resting blood pressure. Weight was measured with participants wearing minimal clothing. Height was measured using a fixed wall stadiometer, with heels together, arms by the side and eyes in the Frankfort plane. WC was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a steel measuring tape placed at the high point of the iliac crest at the end of normal expiration with the participant in a standing position. Race or ethnicity was derived from questions about race and Hispanic origin (non-Hispanic White, Mexican American, non-Hispanic Black and ‘Other’).

Diagnosis of PreHTN

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) criteria for PreHTN (systolic blood pressure: 120–139 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure: 80–89 mm Hg) provided the diagnosis of PreHTN.

Diagnosis. of PreDM

The American Diabetes Association criteria for impaired fasting glucose (fasting serum glucose 100–125 mg dl−1) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (serum glucose 140–199 mg dl−1: 2 h after 75 gm oral glucose tolerance test) provided the diagnosis of PreDM.

Statistical analysis

Data are summarized as counts and percentages±standard error of percentage for categorical variables and means±standard error of mean (s.e.m.) for continuous variables. Prevalence (%) estimates the percentage of healthy US men and women with a condition at the time of data collection and a mean estimates the average value of a characteristic in healthy US adults. All analyses were conducted using weighted procedures specific for sample survey data to account for the complex NHANES sampling design. The calculations were performed using the statistical software SAS Version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA. Large sample z-tests were used to assess statistical significance at P⩽0.05.

Results

Epidemiology

Among the 4,561 disease-free adults investigated in this study, 555 (11.2±0.6%) had coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, 45 (0.6±0.1%) had concurrent unmedicated hypertension and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus, 1,788 (43.3±1.0%) had both normotension and normoglycemia and the remaining 2,173 had other combinations of resting blood pressure and fasting serum glucose concentrations as shown in Table 1. The prevalence of coexisting PreHTN and PreDM (Co-PreHTN+PreDM) increased from 9.5% in 1999–2000 to 12.1% in 2005–2006 (P<0.0001) as shown in Table 2. Men had a higher prevalence of Co-PreHTN+PreDM than women (16.4% vs. 6.1%; P<0.0001). This prevalence increased with age (20–39 years old, 7.8%; 40–59, 14.4%; 60–69, 18.8%), BMI (6.3% for 18.5–<25 kg m−2; 12.8% for 25–<30 kg m−2; 17.0% for >30 kg m−2; P<0.0001) and WC (men: 13.7% if WC<102 cm; 21.0% if >102 cm; P<0.0008; and women: 3.1% if <88 cm; 9.1% if >88 cm; P<0.0001). Non-Hispanic blacks (8.9%) had the lowest prevalence, whereas Mexican Americans (12.5%) had the highest prevalence. Former smokers and consumers of more than five drinks per day had a higher prevalence of coexisting PreHTN and PreDM (P<0.0001).

Adiposity

As shown in Figure 2, a graduated increase in overall prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM was observed with increasing BMI: lean (BMI <18.5 kg m−2), 8.8±4.5%; normal weight (BMI=18.5–24.9 kg m−2), 6.3±0.8%; overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg m−2), 12.8±0.9%; obese (BMI ⩾30 kg m−2), 17.0±1.2%. This trend was observed in both men (10.1±1.5% if normal weight, 17.3±1.4% if overweight and 22.9±1.6% if obese) and women (3.1±0.7%, 5.9±1.0% and 11.4±1.4%, respectively). The association between increased BMI and the prevalence of Co-PreHTN+PreDM was also present within age groups (20–39 years: 5.1±1.0%, 9.5±1.4%, 11.2±1.7%; 40–59 years: 6.5±1.2%, 15.7±1.4%, 22.6±2.4%; 60–69 years: 10.9±3.7%, 20.5±3.6%, 25.1±4.3%; and 70+ years: 15.5±4.6%, 12.4±3.2%, 15.0±4.0%). Further, the prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM increased with BMI within all ethnic groups.

The prevalence of normotension and normoglycemia, coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, and unmedicated hypertension with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus relative to gender and WC is shown in Figure 3. In men with WC<102 cm, the prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM was 13.7±1.3%. It was significantly higher in men with WC>102 cm (21.0±1.4%, P<0.0001). Similarly, the prevalence of Co-PreHTN+PreDM was significantly higher in women with WC>88 cm (9.1±1.0%) when compared with women with WC<88 cm (3.1±0.8%, P<0.0001). Although not shown in the figure, the prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM in men increased with WC in all age groups (20–39 years: 11.9±1.7% for WC<102 cm, 13.8±2.5% for WC>102 cm; 40–59 years: 15.7±1.9% for WC<102 cm, 26.4±2.4% for WC>102 cm; 60–69 years: 23.2±5.5% for WC<102 cm, 24.5±5.3% for WC>102 cm; and 70+ years: 18.2±4.0% for WC<102 cm, 22.0±6.7% for WC>102 cm (all P<0.0001)). This pattern was also found in women (20–39 years: 1.0±0.5% for WC<88 cm, 5.2±1.2% for WC>88 cm; 40–59 years: 4.9±1.4% for WC<88 cm, 11.9±1.8% for WC>88 cm; 60–69 years: 11.3±4.7% for WC<102 cm, 16.4±4.1% for WC>102 cm; and 70+ years: 9.5±5.5% for WC<102 cm, 9.7±3.7% for WC>102 cm (all P<0.0001)). In men, Mexican Americans had the highest overall prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM at 18%, independent of WC, whereas in other ethnic groups, this prevalence was significantly higher with WC>102 cm. Among women in all ethnic groups, the prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM was at least twofold greater in those with WC>88 cm.

Systemic inflammation

The prevalence of systemic inflammation as indicated by C-reactive protein levels was higher in adults with coexistent PreHTN and PreDM (9.0±1.7%) or unmedicated hypertension with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus (16.5±6.3%) compared with in disease-free adults with normotension and normoglycemia (⩾1 mg dl−1: 5.8±0.7%).

Insulin resistance

Fasting insulin levels (8.3±0.2, 14.2±0.7, 17.1±1.3 μU ml−1), HOMA-IR (1.9±0.03, 3.7±0.2, 8.1±1.0) and HbA1C (5.1±0.01, 5.4±0.02, 7.7±0.5%; all P<0.0001) exhibited a graduated increase in adults with normotension and normoglycemia, coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, and unmedicated hypertension with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus, respectively, attesting to increasing insulin resistance.

Blood pressure and pulse pressure

The systolic blood pressure (108.0±0.3, 126.0±0.5, 154.7±2.1 mm Hg), diastolic blood pressure (67±0.2, 75.5±0.5, 76.8±3.2 mm Hg) and pulse pressure (41.0±0.3, 50.5±0.8, 78.0±4.3; all P<0.0001) gradually increased across categories (adults with normotension and normoglycemia, coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, and unmedicated hypertension with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus, respectively), signifying a disruption of blood pressure control.

Lipid subfractions and cardiac risk ratios

Adults with normotension and normoglycemia, coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, and unmedicated hypertension with undiagnosed diabetes mellitus have dysregulated lipid metabolism. The prevalence of high TGs levels (>150 mg dl−1; 17% normal, 41% pre-disease and 69% unmedicated), low HDL-C (<50 mg dl−1 in women 35, 45, 77%; <40 mg dl−1 in men: 26, 39, 39%), above average cardiac risk ratios Total-C/HDL-C (>5: 18, 42, 53%) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)/HDL-C (>3; 21, 41, 50%), respectively, increased as disease burden increased in the study population.

Means for cardiometabolic risk factors

Summary statistics (mean±s.e.m.) for cardiometabolic risk factors are shown in Table 3 for disease-free adults with normotension and normoglycemia, coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, or unmedicated hypertension and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus. The means describing adiposity, insulin resistance, blood pressure control, lipid subfractions and cardiac risk ratios all increased incrementally across blood pressure and glucose categories. The trends of the means for BMI, WC, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, pulse pressure, TG, Total-C and LDL-C were all statistically significant when adults with normotension and normoglycemia were compared with disease-free adults with coexistent PreHTN and PreDM (all P<0.0001). Means for atherogenic LDL-C increased significantly, whereas the means for anti-atherogenic HDL-C decreased significantly, along with significant increases in Total-C/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios (all P<0.001), when adults with normotension and normoglycemia were compared with disease-free adults with coexistent PreHTN and PreDM. These results represent measures outside the accepted desirable range for all parameters.

Number of risk factors (WC, HDL-C and TG) over desirable levels

The prevalence of WC, HDL-C and TGs, three or more of the five risk factors used in the criteria for the metabolic syndrome, is given in Table 4. All adults who had coexistent PreHTN and PreDM had at least one abnormal metabolic risk factor in addition to blood pressure and glucose, but only 52.9% of subjects with both normotension and normoglycemia had one abnormal metabolic risk factor (P<0.0001); 14.2% of adults with early stage coexistent disease had all three additional adverse risk factors, thus, demonstrating undesirable levels for all five risk factors when compared with 5.3% in the basal group.

Discussion

This study brings forth the high prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM in seemingly healthy (disease-free) US adults. The prevalence increases significantly with increasing BMI and WC, two factors, which independently predict elevated CVD risk. The increase of both measures of adiposity is also synonymous with an increased whole body adipose tissue burden.17 A thickening waist (enlarged WC), is associated with accumulation of adipose tissue in the visceral compartment.18 The increasing visceral adipose tissue accumulation renders the visceral adipose tissue dysfunctional, resulting in altered adipose tissue secretions that manifest as enhanced systemic inflammation.19 Overweight adults with larger than desirable WCs and coexistent PreHTN and PreDM also exhibit significantly enhanced systemic inflammation.20

Adults with a large BMI and WC, in parallel with the enhanced systemic inflammation, tend to develop greater insulin resistance. This leads to higher fasting serum insulin levels and, in some individuals, a high-normal level of glycosylated hemoglobin. High insulin levels and glucose concentrations above 100 mg dl−1 are associated with enhanced CVD risk.21 Men and women who have coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, combined with significantly higher BMI and WC, and display elevated C reactive protein, insulin, HOMA-IR and HbA1C have increased insulin resistance.

The increased whole body adipose tissue burden fosters dyslipidemia. Fasting serum total cholesterol, atherogenic low-density cholesterol and TG concentrations tend to increase, whereas the anti-atherogenic high-density cholesterol concentrations tend to decrease. A decrease in anti-atherogenic HDL-C is indicative of an impaired reverse cholesterol transport pathway,22, 23 which over time accelerates atherosclerosis. The increase of the cardiac risk ratios total-C/LDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C above the desirable range attests to an elevated CVD risk.24 Adults with coexistent PreHTN and PreDM as well as significantly higher BMI, WC, elevated C reactive protein, HOMA-IR, high insulin levels and HbA1C also had significantly higher Total-C, LDL-C, TG levels, Total-C/LDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios, and a lower HDL-C. These disease-free adults are on an accelerated pathway to early cardiovascular events. A recent study reported a progressively escalating odds ratio for acute myocardial infarction and stroke increasing from 2.21 times to 2.79, 3.45, 4.35 and 5.73 times in adults with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 abnormal CVD risk factors, respectively, compared with those with no risk factors.25

Hypertension and diabetes mellitus are well established cardiovascular risk enhancing factors. PreHTN and PreDM, although widely perceived as increasing cardiovascular risk, have only been shown to increase cardiovascular risk as one of the components of the metabolic syndrome. We have elucidated the prevalence of PreHTN15 (36.3%) and PreDM (26.8%: unpublished observations) in an otherwise healthy US adult population and have also demonstrated that PreHTN15 and PreDM enhance CVD risk (unpublished observations). With this study, we show that in a representative sample of the United States population, disease-free adults with coexistent PreHTN and PreDM, when compared with men and women with normal blood pressure and normal serum glucose, display statistically significantly higher (or appropriately lower) array of well recognized, evaluated and established risk factors for developing CVD. This, while attesting to a clear and present elevated CVD risk in this population, also underscores an urgent need for recognition, and appropriate intervention aimed at decreasing this risk. Lifestyle modifications: healthier diet (high fiber, whole grain, fruit and vegetable rich, calorie deficit), increased physical activity (at least 150 min per week) and weight loss (7% of current weight) in these otherwise healthy adults with coexisting PreHTN and PreDM could prevent conversion to hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or both. This is a first step in the primary prevention of CVD.

Conclusions

These data highlight the high prevalence of coexistent PreHTN and PreDM in disease-free US adults and depict a potential accelerated pathway to early cardiovascular events.

References

Lee DE, Cooper RS . Recommendations for global hypertension monitoring and prevention. Curr Hypertens Rep 2009; 11: 444–449.

Juutilainen A, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M . Type 2 diabetes as a “coronary heart disease equivalent”: an 18-year prospective population-based study in Finnish subjects. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2901–2907.

Whiteley L, Padmanabhan S, Hole D, Isles C . Should diabetes be considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent?: results from 25 years of follow-up in the Renfrew and Paisley survey. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 1588–1593.

Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Kannel WB, Levy D . Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet 2001; 358: 1682–1686.

De Marco M, de Simone G, Roman MJ, Chinali M, Lee ET, Russell M, Howard BV, Devereux RB . Cardiovascular and metabolic predictors of progression of prehypertension into hypertension. The Strong Heart Study. Hypertension 2009; 54: 974–980.

Edelstein SL, Knowler WC, Bain RP, Andres R, Barrett-Connor EL, Dowse GK . Predictors of progression from impaired glucose tolerance to NIDDM: an analysis of six prospective studies. Diabetes 1997; 46: 701–710.

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P . Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343–1350.

Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Peters RK, Kjos SL, Marroquin A, Goico J . Preservation of pancreatic beta-cell function and prevention of type 2 diabetes by pharmacological treatment of insulin resistance in high-risk Hispanic women. Diabetes 2002; 51: 2796–2803.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393–403.

St-Pierre J, Lemieux I, Perron P, Brisson D, Santuré M, Vohl MC . Relation of the ″hypertriglyceridemic waist″ phenotype to earlier manifestations of coronary artery disease in patients with glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2007; 99: 369–373.

Castelli WP, Doyle JT, Gordon T, Hames CG, Hjortland MC, Hulley SB . HDL cholesterol and other lipids in coronary heart disease. Circulation 1977; 55: 767–772.

Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R . Prospective studies collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002; 360: 1903–1913.

Nielson C, Lange T, Hadjokas N . Blood glucose and coronary artery disease in nondiabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 998–1001.

Saito I, Iso H, Kokubo Y, Inoue M, Tsugane S . Metabolic syndrome and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective (JPHC) Study. Circ J 2009; 73: 878–884.

Gupta A K, McGlone M, Greenway FL, Johnson WD . Prehypertension in disease-free adults: a marker for an adverse cardiometabolic risk profile. Hypertension Research. Hypertens Res 2010; 33: 905–910.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. Accessed. August 2009.

Jensen M D . Role of Body Fat Distribution and the Metabolic Complications of Obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: S57–S63.

Blüher M . Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2009; 117: 241–250.

Bakhai A . Adipokines—targeting a root cause of cardiometabolic risk. QJM 2008; 101: 767–776.

Gupta AK, Johnson WD . Prediabetes and prehypertension in disease-free obese adults correlate with an exacerbated systemic proinflammatory milieu. J Inflamm (Lond) 2010; 7: 36.

Barr EL, Cameron AJ, Balkau B, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA, Tonkin AM . HOMA insulin sensitivity index and the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease events in the general population: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab) study. Diabetologia 2010; 53: 79–88.

Tamada M, Makita S, Abiko A, Naganuma Y, Nagai M, Nakamura M . Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as a useful marker for early-stage carotid atherosclerosis. Metabolism 2010; 59: 653–657.

Toth PP . Reverse cholesterol transport: high-density lipoprotein's magnificent mile. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2003; 5: 386–393 (Review).

Gupta AK, Ross EA, Myers JN, Kashyap ML . Increased reverse cholesterol transport in athletes. Metabolism 1993; 42: 684–690.

Malone DC, Boudreau DM, Nichols GA, Raebel MA, Fishman PA, Feldstein AC . Association of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Prevalent Cardiovascular Events. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2009; 7: 585–593.

Acknowledgements

AKG composed the manuscript. MG and WDJ worked on the database from NHANES, composed the tables and figures, and participated in the editing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Presented at the annual meeting of The American Society of Hypertension, 2010.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, A., Brashear, M. & Johnson, W. Coexisting prehypertension and prediabetes in healthy adults: a pathway for accelerated cardiovascular events. Hypertens Res 34, 456–461 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.267

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.267

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Different combinations of glucose tolerance and blood pressure status and incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality events

Journal of Human Hypertension (2017)

-

Fasting glucose and HbA1c levels as risk factors for the development of hypertension in Japanese individuals: Toranomon hospital health management center study 16 (TOPICS 16)

Journal of Human Hypertension (2015)

-

Cardio-metabolic risk factors and prehypertension in persons without diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease

BMC Public Health (2013)

-

High prevalence of coexisting prehypertension and prediabetes among healthy adults in northern and northeastern China

BMC Public Health (2011)

-

Dysglycemia induces abnormal circadian blood pressure variability

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2011)