Abstract

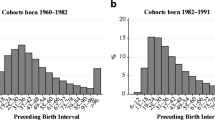

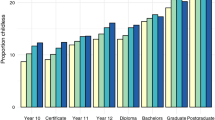

Objectives. Advanced maternal age at first birth, but not at subsequent births, may have detrimental health implications for both mother and child, such as a poor birth outcome and an increased risk of maternal breast cancer. However, positive outcomes may also result such as an improvement in economic measures and offspring's performance on cognitive tests. Research has indicated that women increasingly are delaying their first births beyond the early twenties, but the recent trends in socioeconomic disparity in age at first birth, and the implications for public health, have not been well described. Method. This study used national birth certificate data for 1969–1994 to examine age at first birth by maternal education level. Current Population Survey data were also used to examine changes over time in age and educational distribution among women of childbearing age. Results. Age at first birth increased during the time period. Median age at first birth increased from 21.3 to 24.4 between 1969 and 1994, and the proportion of first-time mothers who were age 30 or older increased from 4.1% to 21.2%. Age at first birth increased rapidly among women with 12 or more years of education; nearly half (45.5%) of college graduate women who had their first birth in 1994 were age 30 or older, compared with 10.2% in 1969. However, little change was observed among women with fewer than 12 years of education; among those with 9–11 years of education, only 2.5% of first births in 1994 occurred at age 30 or older. Conclusions. The trend toward postponed childbearing has occurred primarily among women with at least a high school education. Health services use, such as infertility treatment and cesarean section, may increase as a result of delayed childbearing among higher educated women. Future examinations of the association between maternal age at first birth and health outcomes may need to take greater account of socioeconomic differentials.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Niswander KR, Gordon M. The women and their pregnancies. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Co., 1972.

Cnattingius S, Forman MR, Berendes HW, Isotalo L. Delayed childbearing and risk of adverse perinatal outcome. A population-based study. JAMA 1992; 268:886–90.

Kiely JL, Paneth N, Susser M. An assessment of the effects of maternal age and parity in different components of perinatal mortality. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 123:444–54.

Berendes HW, Forman MR. Delayed childbearing: trends and consequences. In: Kiely M editor. Reproductive and perinatal epidemiology. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 1991:27–41.

Hansen JP. Older maternal age and pregnancy outcome: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1986; 41:726–42.

Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Mathews TJ, Clarke SC. Advance report of final natality statistics, 1994. Monthly vital statistics report; Vol. 44, No. 11, Suppl. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1996.

Williams MA, Lieberman E, Mittendorf R, Monson RR, Schoenbaum SC. Risk factors for abruptio placentae. Am J Epidemiol 1991;134:965–72.

Naeye RL. Maternal age, obstetrical complications, and the outcome of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1983;61:210–16.

Stein ZA. A woman's age: Childbearing and child rearing. Am J Epidemiol 1985; 121:327–42.

Menken J, Trussell J, Larsen U. Age and infertility. Science 1986; 233:1389–94.

Kelsey JL, Horn-Ross PL. Breast cancer: Magnitude of the problem and descriptive epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev 1993;15:7–16.

Curtin SC. Rates of cesarean birth and vaginal birth after previous cesarean, 1991–95. Monthly vital statistics report, Vol. 45, No. 11, Suppl. 3. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1997.

Mathews TJ, Ventura SJ. Birth and fertility rates by educational attainment: United States, 1994. Monthly vital statistics report; Vol. 45, No. 10, Suppl. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1997.

Wilkie JR. The trend toward delayed parenthood. J Marriage Family 1981;43:583–91.

Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. Maternal age and cognitive and behavioural outcomes in middle childhood. Paediatric Perinat Epidemiol 1993;7:77–91.

Hofferth SL. Long-term economic consequences for women of delayed childbearing and reduced family size. Demography 1984;21:141–55.

Baldwin WH, Nord CW. Delayed childbearing in the U.S.: Facts and fictions. Pop Bull 1984;39:1–43.

Kiernan KE, Diamond I. The age at which childbearing starts—a longitudinal study. Pop Stud 1983;37:363–80.

Lewis C, Ventura S. Birth and fertility rates by education: 1980 and 1985. Vital Health Stat 1990;21(49).

Marini MM. Women's educational attainment and the timing of entry into parenthood. Am Sociol Rev 1984;49:491–511.

Rindfuss RR, St. John C. Social determinants of age at first birth. J Marriage Family 1983;45:553–65.

Rindfuss RR, Bumpass L, St. John C. Education and fertility: Implications for the roles women occupy. Am Sociol Rev 1980;45:431–47.

Wineberg H. Education, age at first birth, and the timing of fertility in the United States: Recent trends. J Biosoc Sci 1988;20:157–65.

Loh S, Ram B. Delayed childbearing in Canada: Trends and factors. Genus 1990;66:147–61.

St. John C. Race differences in age at first birth and the pace of subsequent fertility: Implications for the minority group status hypothesis. Demography 1982;19:301–14.

Maxwell NL. Influences on the timing of first childbearing. Contemp Policy Issues 1987;5:113–22.

Evans MDR. American fertility patterns: A comparison of white and nonwhite cohorts born 1903–56. Pop Devel Rev 1986;12:267–93.

Lehrer E. Female labor force behavior and fertility in the United States. Ann Rev Sociol 1986;12:181–204.

Ventura SJ. Trends and variations in first births to older women, 1970–86. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1989;21(47).

Rindfuss RR, Morgan SP, Offutt K. Education and the changing age pattern of American fertility: 1963–1989. Demography 1996;33:277–90.

National Center for Health Statistics. Public Use Data File Documentation. Natality Data. Hyattsville, MD: NCHS, annual (1969–1994).

SAS procedures guide, version 6, 3rd ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc., 1990.

United States Bureau of the Census. Current Population Survey, June 1990: Fertility Technical Documentation, 1991.

Day J, Curry A. Education attainment in the United States: March 1995, Series P20-489. Detailed tables for Current Population Reports (PPL-48). U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1997.

Hansen KA, Bachu A. The foreign-born Population: 1994. Current Population Reports, Series P20-486. U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1995.

Hayes CD (ed.). Risking the future. National Research Council (U.S.). Panel on Adolescent Pregnancy in Childbearing, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1987.

National Center for Health Statistics. Report to Congress on out-of-wedlock childbearing. Hyattsville, MD: NCHS, 1995.

Rindfuss RR, Bumpass LL. How old is too old? Age and the sociology of fertility. Family Plan Perspect 1976;8:226–30.

Chandra A, Mosher WD. The demography of infertility and the use of medical care for infertility. Infertil Reprod Med Clin North Am 1994;5:283–96.

Menken J. Age and fertility: How late can you wait? Demography 1985;22:469–83.

Chen R, Morgan SP. Recent trends in the timing of first births in the United States. Demog 1991;28:513–33.

Bachu A. Fertility of American Women: June 1992. Current Population Reports, Series P20-470. U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1993.

Abma JC, Chandra A, Mosher WD, Peterson LS, Piccinino LJ. Fertility, family planning, and women's health: estimates from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat, Ser. 23, No. 19, May 1997.

Taubman P, Behrman JR. Effect of number and position of siblings on child and adult outcomes. Soc Biol 1986;33:22–34.

McLanahan SS. The consequences of nonmarital childbearing for women, children, and society. In: Report to Congress on Out-of-Wedlock Childbearing. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1995:229–39.

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1997. Current Population Reports, Series P60. Educational Attainment of Householder—Families with Householder 25 Years Old and Over by Median and Mean Income: 1991 to 1995.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heck, K.E., Schoendorf, K.C., Ventura, S.J. et al. Delayed Childbearing by Education Level in the United States, 1969–1994. Matern Child Health J 1, 81–88 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026218322723

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026218322723