Abstract

Background

In the largest overhaul to Medicare since its creation in 1965, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 established Part D in 2006 to improve access to essential medication among disabled and older Americans. Despite previous evidence of a positive impact on the general Medicare population, Part D’s overall effects on long-term care (LTC) are unknown.

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the literature regarding Part D’s impact on the LTC context, specifically costs to LTC residents, providers and payers; prescription drug coverage and utilization; and clinical and administrative outcomes.

Data sources

Four electronic databases [PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Health Business Fulltext Elite and Science Citation Index Expanded], selected US government and non-profit websites, and bibliographies were searched for quantitative and qualitative studies characterizing Part D in the LTC context. Searches were limited to studies that may have been published between 1 January 2006 (date of Part D implementation) and 8 January 2013.

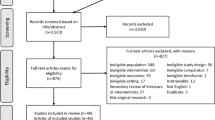

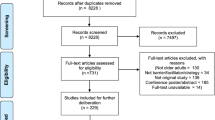

Study selection

Systematic searches identified 1,624 publications for a three-stage (title, abstract and full-text) review. Included publications were in English language; based in the US; assessed Part D-related outcomes; and included or were directly relevant to LTC residents or settings. News articles, reviews, opinion pieces, letters or commentaries; case reports or case series; simulation or modeling studies; and summaries that did not report original data were excluded.

Study appraisal and synthesis methods

A standardized form was used to abstract study type, study design, LTC setting, sources of data, method of data collection, time periods assessed, unit of observation, outcomes and results. Methodological quality was assessed using modified criteria specific to quantitative and qualitative studies.

Results

Eleven quantitative and eight qualitative studies met inclusion criteria. In the seven years since its implementation, Part D decreased out-of-pocket costs among enrolled nursing home residents and potentially increased costs borne by LTC facilities. Coverage of prescription drugs frequently used by older adults was adequate, except for certain drugs and alternative formulations of importance to LTC residents. The use of medications that raise safety concerns was decreased, but overall drug utilization may have been unaffected. Although there was uncertain impact on clinical outcomes, quantitative studies demonstrated evidence of unintended health consequences. Qualitative studies consistently revealed increased administrative burden among providers.

Limitations

Empirical evidence of Part D’s LTC impact was sparse. Due to limitations in available types of data, quantitative studies were generically lacking in methodological rigor. Qualitative studies suffered from lack of clarity of reporting. As future studies use clinical Medicare data, study quality is expected to improve.

Conclusion

Although LTC-specific policies continue to evolve, it appears that the prescription drug benefit may require further modifications to more effectively provide for LTC residents’ unique medication needs and improve their health outcomes. Adjustments may be needed for Part D to be more compatible with LTC prescription drug delivery processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare: a primer. Menlo Park: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. Report no.: 7615-03.

Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, HR 1/Pub. L. No. 108-173, 117 Stat. 2066 (2003).

Edelman TS. Medicare prescription drug coverage for residents of nursing homes and assisted living facilities: special problems and concerns. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. Report no.: 7342.

Harrington C, Carrillo H, Blank BW, et al. Nursing facilities, staffing, residents and facilities deficiencies, 2004 through 2009 [online]. http://www.pascenter.org/documents/OSCAR_complete_2010.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2012.

Stuart B, Simoni-Wastila L, Baysac F, et al. Coverage and use of prescription drugs in nursing homes: implications for the Medicare Modernization Act. Med Care. 2006;44(3):243–9.

Avorn J, Gurwitz JH. Drug use in the nursing home. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(3):195–204.

Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, et al. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. Vital Health Stat 13. 2009;(167):1–155.

Hing E, Bloom B. Long-term care for the functionally dependent elderly. Vital Health Stat 13. 1990;(104):1–50.

Requirements for States and Long Term Care Facilities, 42 C.F.R § 483.60 (2006).

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Distribution of certified nursing facility residents by primary payer source, 2010 [online]. http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparebar.jsp?ind=410&cat=8. Accessed 18 Jan 2013.

US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare prescription drug benefit manual, Chapter 6—Part D Drugs and Formulary Requirements [online]. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/downloads/Chapter6.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2012.

Voluntary Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit, 42 C.F.R § 423.782 (2005).

Lau DT, Briesacher BA, Touchette DR, et al. Medicare Part D and quality of prescription medication use in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(10):797–807.

Polinski JM, Donohue JM, Kilabuk E, et al. Medicare Part D’s effect on the under- and overuse of medications: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1922–33.

Polinski JM, Kilabuk E, Schneeweiss S, et al. Changes in drug use and out-of-pocket costs associated with Medicare Part D implementation: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1764–79.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Lohr KN, Carey TS. Assessing “best evidence”: issues in grading the quality of studies for systematic reviews. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1999;25(9):470–9.

Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT, editors. Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 4.2.2 [updated March 2004]. The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Chichester: Wiley; 2004.

Moher D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized trials: implications for the conduct of meta-analyses. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3(12):i–iv 1–98.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Stevenson DG, Huskamp HA, Newhouse JP. Medicare Part D, nursing homes, and long-term care pharmacies. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2007. Report no.: 07-2.

Stevenson DG, Huskamp HA, Newhouse JP. Medicare Part D and the nursing home setting. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):432–41.

Bazalo G, Weiss R. Measurement of unused medication in Medicare Part D residents in skilled nursing facilities. Consult Pharm. 2011;26(9):647–56.

Bazalo G, Weiss RC. Impact of final short-fill rule on Medicare Part D costs and long-term care pharmacy dispensing. Consult Pharm. 2012;27(4):269–73.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Availability of Medicare Part D drugs to dual-eligible nursing home residents. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008 Jun. Report no.: OEI-02-06-00190.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Role of nursing homes and long term care pharmacies in assisting dual-eligible residents with selecting Part D plans. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008 Jun. Memorandum report no.: OEI-02-06-00191.

Briesacher BA, Soumerai SB, Field TS, et al. Nursing home residents and enrollment in Medicare Part D. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(10):1902–7.

Briesacher BA, Soumerai SB, Field TS, et al. Medicare Part D’s exclusion of benzodiazepines and fracture risk in nursing homes. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):693–8.

Golden AG, Qiu D, Roos BA. Medication assessments by care managers reveal potential safety issues in homebound older adults. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(4):492–8.

Huskamp HA, Stevenson DG, Keating NL, et al. Rejections of drug claims for nursing home residents under Medicare Part D. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):560–7.

Stevenson DG, Huskamp HA, Keating NL, et al. Medicare Part D and nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):1115–25.

Stevenson DG, Keohane LM, Mitchell SL, et al. Medicare Part D claims rejections for nursing home residents, 2006 to 2010. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(10):647–54.

West JC, Wilk JE, Rae DS, et al. First-year Medicare Part D prescription drug benefits: medication access and continuity among dual eligible psychiatric patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(4):400–10.

Wilk JE, West JC, Rae DS, et al. Medicare Part D prescription drug benefits and administrative burden in the care of dually eligible psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(1):34–9.

Cote BR, Petersen EA. Impact of therapeutic switching in long-term care. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(11 Suppl):SP23–8.

Raehl C, Maclaughlin E, Patry R, et al. Early implementation of Medicare Part D in urban and rural nursing facilities. Consult Pharm. 2007;22(9):744–53.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Impact of reassignment in the Part D program on health outcomes. Baltimore: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2009.

US Government Accountability Office. Medicare Part D: challenges in enrolling new dual-eligible beneficiaries. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2007. Report no.: GAO-07-272.

US Government Accountability Office. Many factors, including administrative challenges, affect access to Part D vaccinations. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2011. Report no.: GAO-12-61.

Huskamp HA, Oakman TS, Stevenson DG. Medicare Part D and its impact in the nursing home sector: an update. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2010. Report no.: 10-4.

Buchsbaum L, Varon J, Kagel E, et al. Perspectives on Medicare Part D and dual eligibles: key informants’ views from three states. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry K. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007. Report no.: 7639.

Jung C. Impact of Medicare Part-D on generic drug utilization in the long-term care facilities [online]. http://www.heinz.cmu.edu/research/377full.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2013.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare Part D prescription drug plan [PDP] availability in 2013. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. Publication no. 7426-09.

Voluntary Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit, 42 C.F.R § 423.32; 2005.

US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Survey and Certification Group. Nursing homes and Medicare Part D. Baltimore, MD: US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2006. Memorandum reference no.: S&C-06-16.

US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS guide to requests for Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event (PDE) data [online]. Baltimore, MD: US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2008 Aug 15. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/downloads/GuidePartDDataRequests.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2012.

Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Residents living in residential care facilities: United States, 2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;91:1–8.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Briesacher conceived of the overall study objective. Ms. Pimentel acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. Drs. Briesacher and Lapane made substantive revisions to the manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

There was no funding source for this study. During the preparation of this manuscript, Dr. Briesacher was supported by research scientist award K01AG031836. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging. All authors declare that no potential conflicts of interest exist, including financial interests or affiliations relevant to the subject of this review.

We gratefully acknowledge Drs. Jane Saczynski, Jerry Gurwitz, Robin Clark, Allison Rosen, Marc Philip Pimentel and Ms. Alexandra Hajduk for their guidance and helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. We sincerely thank Ms. Sally Gore for her assistance in developing our systematic search strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pimentel, C.B., Lapane, K.L. & Briesacher, B.A. Medicare Part D and Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. Drugs Aging 30, 701–720 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0096-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0096-6