ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Patients with low socioeconomic status (low-SES) are at risk for poor outcomes during the post-hospital transition. Few prior studies explore perceived reasons for poor outcomes from the perspectives of these high-risk patients.

OBJECTIVE

We explored low-SES patients’ perceptions of hospitalization, discharge and post-hospital transition in order to generate hypotheses and identify common experiences during this transition.

DESIGN

We conducted a qualitative study using in-depth semi-structured interviewing.

PARTICIPANTS

We interviewed 65 patients who were: 1) uninsured, insured by Medicaid or dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare; 2) residents of five low-income ZIP codes; 3) had capacity or a caregiver who could be interviewed as a proxy; and 4) hospitalized on the general medicine or cardiology services of two academically affiliated urban hospitals.

APPROACH

Our interview guide investigated patients’ perceptions of hospitalization, discharge and the post-hospital transition, and their performance of recommended post-hospital health behaviors related to: 1) experience of hospitalization and discharge; 2) external constraints on patients’ ability to execute discharge instructions; 3) salience of health behaviors; and 4) self-efficacy to execute discharge instructions. We used a modified grounded theory approach to analysis.

KEY RESULTS

We identified six themes that low-SES patients shared in their narratives of hospitalization, discharge and post-hospital transition. These were: 1) powerlessness during hospitalization due to illness and socioeconomic factors; 2) misalignment of patient and care team goals; 3) lack of saliency of health behaviors due to competing issues; 4) socioeconomic constraints on patients’ ability to perform recommended behaviors; 5) abandonment after discharge; and 6) loss of self-efficacy resulting from failure to perform recommended behaviors.

CONCLUSIONS

Low-SES patients describe discharge goals that are confusing, unrealistic in the face of significant socioeconomic constraints, and in conflict with their own immediate goals. We hypothesize that this goal misalignment leads to a cycle of low achievement and loss of self-efficacy that may underlie poor post-hospital outcomes among low-SES patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

Prior research has demonstrated that patients with low socioeconomic status (low-SES) are at greater risk for experiencing poor outcomes during the post-hospital transition, including readmission and death across a variety of diseases.1–11 This observation has led to substantial debate about whether SES should have been included in the readmission measurement models used to calculate the October 2012 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) readmissions penalty.12 By deciding to exclude SES, CMS effectively placed the onus on hospitals to address socioeconomic disparities in post-hospital outcomes, rather than being able to adjust for these differences.13

In order to reduce disparities, hospitals and providers will need a deeper understanding of factors that drive poor transition outcomes for low-SES patients. Prior studies suggest that, in general, patients and caregivers attribute failed transitions to a lack of preparedness for discharge,14–17 a sense of exclusion from discussions of the care plan,14,18 abandonment by the health care system after discharge15,19 and lack of adherence to discharge recommendations.20,21 Despite the fact that low-SES patients are at higher risk for poor outcomes, few prior studies specifically explore the perspectives of these patients.22 One qualitative study of 21 patients served in low-income community health centers suggested that low-SES patients knew their diagnoses, medications and discharge instructions, but faced other non-knowledge barriers to recovery such as stress, difficulty paying for home care and lack of transportation.22

Building on this prior work, we set out to further explore low-SES patients’ perceptions of hospitalization, discharge and the post-hospital transition, and to investigate factors influencing performance of health behaviors recommended for post-hospital recovery. Due to the relative dearth of existing evidence, we chose a qualitative approach with the goal of generating hypotheses and identifying common experiences of low-SES patients during the post-hospital transition.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a qualitative study of 65 patients hospitalized between January of 2011 and November of 2012. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania. Patients were: 1) uninsured, insured by Medicaid or dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare; 2) residents of a five-ZIP code region of Philadelphia in which greater than 30 % of residents live below the Federal Poverty Level; 3) able to achieve a score of 23 or above on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) or had a caregiver who could be interviewed as a proxy; and 4) hospitalized on the general medicine or cardiology services of two academically affiliated urban hospitals, both of which are located in Philadelphia and serve a population that is predominantly African-American, publicly insured and uninsured. Patients were purposefully selected to provide a range in insurance types (uninsured, insured by Medicaid and dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare) and frequency of visits to the emergency room in the 6 months prior to enrollment. We chose this sampling strategy in order to be able to make comparisons by insurance and frequency of utilization.

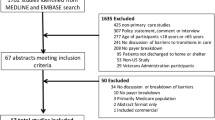

We invited 149 eligible patients to participate in the study during their hospitalization. Of these 149, 68 refused because they: were not interested (n = 24); lacked capacity and had no caregiver who could be interviewed as a proxy (n = 17); felt too sick to participate (n = 15); were too busy (n = 14); did not feel that participation would benefit them (n = 12); were hearing-impaired (n = 5); or had privacy concerns (n = 1). Of the 81 patients that provided written consent, 16 patients were unable to schedule a mutually agreeable time for the interview, leaving a final sample size of 65.

Data Collection

All interviews were conducted by one of the authors, TC, a member of the community who shared life circumstances with the target population. We hired and trained TC in order to give voice to marginalized patients who had mistrust of traditional research personnel. TC was selected by the principal investigator from a pool of 15 applicants for the position of ‘community-based interviewer’ for her natural listening skills, reliability, and experience with community outreach. TC was employed by the Mixed Methods Research Laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania and underwent rigorous training on human subjects research and qualitative interviewing. TC approached eligible patients while they were hospitalized in order to obtain consent. Interviews were conducted within 30 days after index hospitalization either in the hospital or in patients’ homes. The mean number of days from index discharge to time of the interview was 23 (SD 13).

We used the Integrative Behavior Model (IBM)29 as a conceptual framework for the development of a semi-structured interview guide (Online Appendix A). The IBM posits that it is possible to know why a person does or does not perform health behaviors by understanding certain key variables: social norms, habit, knowledge and skills, experiential attitudes, environmental constraints, salience of the behavior and self-efficacy.

Social norms and habit are difficult to assess when dealing with a diversity of diseases and required health behaviors. Knowledge and skills have been explored by Strunin et al. whose work suggested that these domains were not very influential in the post-discharge course of low-SES patients.22 Therefore, our guide focused on how low-SES patients’ performance of recommended post-hospital health behaviors related to the remaining domains of the IBM.

First, we explored patients’ experience of hospitalization and discharge. Prior literature on SES and trust23,24 suggests that low-SES patients’ experience of care may be influenced by perceived institutional racism and classism. We were interested in exploring whether these perceptions would influence patients’ willingness to follow discharge recommendations. Second, we explored external socioeconomic constraints on patients’ ability to perform recommended health behaviors required for recovery. Third, we explored salience of recommended health behaviors. Prior work has suggested that health behaviors lack salience to homeless individuals because of more pressing competing issues.25,26 Finally, we explored patients’ self-efficacy to execute recommended health behaviors. Work by Bandura et al.27–29 suggests that low-SES is associated with low self-efficacy. This might be particularly detrimental during the post-hospital transition, as patients require self-efficacy to perform challenging self-care behaviors while recovering from an acute illness.

The interview questionnaire was semi-structured and open-ended which allowed interviewees to respond in their own words. We piloted our interview guide for ease of comprehensibility with five participants whose transcripts were not included in the final study results. Interviews were audio-taped, transcribed and imported into NVivo 10.0 for coding and analysis.

Analysis

We used a modified grounded theory approach31 to analysis: the entire study team developed a coding structure (Online Appendix B) that included major ideas that emerged from a close reading of the data, as well as a set of a priori codes based upon the IBM. Coding and analysis occurred in an iterative process with interviewing; this allowed us to modify the interview guide and coding structure in order to more deeply explore themes that emerged from our analysis.

All coding was performed by two research assistants who were trained by the investigators in qualitative coding and analysis. Codes were discussed at coding meetings by all members of the study team, including the community-based interviewer. We used the inter-rater reliability function in NVivo to gauge agreement in coding. During meetings, we identified codes for which the inter-rater reliability (IRR) was below 70% and resolved discrepancies by consensus. The final IRR between coders was 93.3%.

As we analyzed the data, we used two forms of member checking in order to validate our results: First, the community-based interviewer called each study participant to explain findings and obtain feedback. Second, the community-based interviewer and principal investigator discussed study findings at meetings of community organizations located in the study ZIP codes. The community-based interviewer presented member feedback during coding meetings, informing ongoing analysis.

RESULTS

We analyzed interviews from 65 patients: 41 (63 %) were female, 62 (95 %) were African American, and the mean age was 52 (range 18–93) (Table 1).

We identified six themes that low-SES patients shared in their narratives of hospitalization, discharge and post-hospital transition (Table 2). These were: 1) powerlessness during hospitalization due to illness and socioeconomic factors; 2) misalignment of patient and care team goals; 3) lack of saliency of health behaviors due to competing issues; 4) socioeconomic constraints on patients’ ability to perform recommended behaviors; 5) abandonment by social supports and the health care system after discharge; and 6) loss of self-efficacy resulting from failure to perform recommended behaviors.

Powerlessness During Hospitalization

Patients conveyed a feeling of powerlessness that came with being acutely ill and hospitalized. One patient explained, “Everything is up in the air, like hopes and maybes… nothing I could do but sit here and wait until they figure out something (age 49, Male, Medicaid).” The complexity of the inpatient care team made it even harder for patients to feel empowered in their care: “When you’re bombarded with five or ten doctors every day, the medical students and all, you don’t understand everything that happens or what they do (age 74, Female, Dually eligible).”

These feelings of helplessness were heightened for those who were uninsured. Despite the fact that most hospital providers do not know patients’ insurance status, uninsured patients perceived that the hospital staff was aware and that this knowledge influenced their care. “You got A1 insurance, rushing down the hall, STAT, give the best—when I didn’t have insurance I felt the difference in the treatment (age 39, Female, Uninsured).” Uninsured patients felt a sense of shame and self-consciousness that affected their interactions with hospital staff. “We are working people. We have no insurance. This is an embarrassment…and you just feel so bad when you’re at the hospital (age 56, Female, Uninsured).” Even insured patients felt that the emphasis on insurance status during registration signaled hospitals’ priorities: “When you go in there, it’s like: ‘You got any insurance? All right. What’s the problem?’ It’s like let me see if she got good insurance first before I get to treating her nice and start the treatment (age 39, Female, Uninsured).” Ultimately, the uninsured and those with tenuous insurance perceived that they were beholden to the hospital for their care: “I’m at the mercy of this university (age 49, Male, Medicaid),” a patient summarized.

Misalignment of Patient and Care Team Goals

Many low-SES patients felt that providers could not relate to the constraints that they would face upon leaving the hospital. One patient explained, “You can’t blame the nurses and doctors. They can give you the advice, like here’s the kind of medicine you need. But they don’t really know how it works in the real world (age 42, Male, Medicaid).”

As a result of this disconnect, discharge plans dictated by providers were often misaligned with patients’ realities: “I didn’t have insurance or a regular doctor. So, dealing with the doctor at discharge, it was like me and him wasn’t on the same page. It was a mix-up of what he expected out of me and what I expected out of him, upon being discharged (age 42, Male, Medicaid).” In some cases, discharge instructions were unrealistic given patients’ constraints: “They’re telling me to weigh myself every day…I don’t even have a place to stay, how am I supposed to do that (age 41, Female, Medicaid)?” In other cases, discharge goals were in conflict with existing goals that were more important to the patient. One patient stated, “[The doctor] wants me to exercise, and I’m just trying to tell them, as soon as I get some time I’m gonna try to do that. I did it in the summertime, because I wasn’t working as much. But right now, I need to work a little harder for a paycheck. I got some goals I’m trying to achieve (age 34, Male, Uninsured).”

Several factors made it difficult for low-SES patients to question or challenge misaligned discharge goals. The first was that discharge was often unexpected. One patient explained, “It was very sudden. They’re like—one minute I was sitting in there waiting for a test, the next thing they said, oh, you can go home (age 49, Male, Medicaid).” The rapidity of the discharge process did not allow patients the additional time they required to assess feasibility of instructions and plan for the unique barriers they would face upon discharge: “[Discharge] is a scary experience…they need to give you some time to think, calm down and figure out what’s going on, before they actually throw you out (age 47, Dually eligible).”

The second factor that impeded a negotiation of discharge goals was the fact that patients with low health literacy often had difficulty even understanding discharge instructions. One patient described the process of receiving discharge instructions as “nerve-wracking and hard, because some of this stuff you don’t even understand. I’m not a great reader. Academically I’m not smart. So, I get my medicines all mixed up. I knew I was messing up real bad (age 45, Male, Dually eligible).” Patients emphasized that written discharge instructions should not replace a careful verbal explanation because of literacy issues: “Maybe you should go over them and even though you write them professionally, make sure that the patient understands (age 74, Female, Dually eligible).”

Finally, some patients hesitated to have a real dialogue with providers about discharge goals. Patients sensed that their providers were too busy to discuss discharge plans in detail: “You can’t ask doctors or nurses questions even if you don’t understand because they don’t keep still long enough (age 72, Male, Dually eligible).” Pride sometimes prevented patients from admitting that they could not understand discharge instructions or perform recommendations due to cost. “You know [the providers] are already looking down on you…I could not afford the things they wanted me to get, but I could not get the words out of my mouth. My pride stopped me from asking [for help] (age 45, Female, Uninsured).”

Lack of Saliency of Health Behaviors

After discharge, many patients were more focused on dealing with pressing socioeconomic challenges than on performing discharge instructions. One patient explained that after discharge, she voluntarily called the Department of Humans Services (DHS) in order to receive housing assistance. “I know that DHS needs to really focus on kids that’s getting hurt, but I’m a mom who—I’m single. I don’t have the being to take care of my baby. It would just be like me and him being on the streets. So help us not to get there (age 34, Female, Medicaid).”

Some patients attributed their inability to follow discharge instructions to socioeconomic stressors. A patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) confessed: “I smoke cigarettes. I found out I got to leave the cigarettes alone, which I was trying to do, but you know, the nerves bad…bill worries and all that. And I’m the Mommy and the Daddy and when everything is on you, a person can only take so much (age 49, Female, Medicaid).” Another patient, when asked what made it hard for him to stay healthy after discharge explained, “Well, I got the worries. I worry about where I’m living at. It’s in the projects. There’s a lot of drugs, lot of guys around a lot. When I worry, it seems like I start feeling my sickness coming on (age 58, Male, Medicaid).”

Socioeconomic Constraints on Patients’ Ability to Perform Recommended Behaviors

Most low-SES patients described some financial barriers to executing their discharge plans as recommended by hospital providers. Most commonly, patients explained that appointment copays or discharge medications were unaffordable. If the discharging physician did not prescribe a formulary medication, even insured patients had surprisingly large copays: “I have insurance, but they don’t pay for everything [the doctor] wanted me to get…there was the shock of it not being covered when I got to the pharmacy (age 42, Male, Medicaid).”

Several patients were unable to pay for recommended post-acute care, such as drug rehab or skilled nursing facilities. A heroin-addicted patient who had been readmitted multiple times for soft tissue infections and endocarditis said, “Every time I turn around I’m in the hospital because I’m sick from [the drugs]. So, I’m trying to get into rehab after the hospital so I can wean down. But my insurance situation isn’t that great, so, they keep turning me away and I get put back into the same situation again, back to the streets and using drugs again (age 25, Female, Uninsured).”

Finally, patients’ financial issues had indirect effects on the post-hospital recovery. Patients reported feeling pressure to return to their employment before they fully recovered, so that they could resume earning wages or avoid being fired. One patient explained, “I knew that my paycheck was going to be cut a little short from missing the days being in the hospital…I’m just glad they didn’t fire me from just being in the hospital, because you know, some jobs you take 2 days off back-to-back, you gone (age 35, Female, Medicaid).”

Abandonment by Social Supports and the Health Care System

Patients began to fully appreciate the difficulties of performing discharge instructions once they left the hospital and faced competing issues and financial barriers. One patient explained, “It was good leaving the hospital and going home [at first]. But soon I got upset… you’re getting waited on in the hospital with your meds and you don’t have to worry. Then you go home and the reality of having to do all of those things your own, and real life (age 42, Male, Medicaid).” It was at this point of recovery that patients commonly described a sense of abandonment by their social supports as well as the health care system.

Some patients described dysfunction within their social networks: “My kid’s father is drinking, lots of drinking. So even though I’m going through something medical, I’m unable to take care of myself, because I’m dealing with him (age 55, Female, Medicaid).” Other patients describe emotionally supportive social networks; however, these networks were comprised of people who are also poor and often themselves ill. One patient who signed out of the hospital against advice explained that her caregiver responsibilities superseded her own health: “I don’t like to stay at the hospital and worry about my daughter, she’s an epileptic. I’m comfortable with her with my sister and them, but my daughter sleeps with me because she has all types of seizures, the ones in the sleep. She’s hitting the bed and stuff like that. I just get all—she all right? What’s she doing? She breathing? I just—the nervousness start coming (age 41, Female, Medicaid).”

Conversely, many disabled or elderly patients explained that they felt reluctant to “trouble” friends or family for help during recovery because they “got their own problems”. As one patient explained, “my children have to work. Everybody is in different parts of the city and nobody had transportation. So, I have to fend for myself (age 65, Female, Dually eligible).” Several caregivers of disabled patients explained that their own health problems made it difficult to care for patients during post-hospital recovery: “I’m not in the best of health myself…I have heart problems, so it is rough [to take care of my father] (age 79, Male, Dually eligible).”

Frequently, patients also felt abandoned by the health care system once they left the hospital: “Because once they let you out the hospital, that’s it, you gone. You no longer our responsibility (age 56, Female, Uninsured).” Patients explained that they were unable to get back in touch with their inpatient care team in order to get clarification or adjust discharge plans when financial barriers arose. One patient said, “They referred me to another specialist, but I found out that I don’t have the money…I called where I was scheduled to be at and couldn’t get help (age 74, Female, Dually eligible).” Another patient explained: “I had some mix-up in my prescriptions and I called back to the hospital to speak to the doctor. And I was just on hold for a long time. I called like four times to speak to the doctor and no one ever called me back. So then my leg started swelling up even more, up to my thighs…I ended up back in the hospital (age 61, Female, Medicaid).”

Loss of Self-Efficacy Resulting from Failure

Ultimately, patients described that the consequence of misaligned discharge goal-setting, external constraints and lack of support, was failure to perform recommended health behaviors. This feeling of being “set up to fail” led patients to “not even want to try.” One patient summarized the loss of self-efficacy that resulted from perceived failure to perform: “I knew I couldn’t do the things they were asking me to do. So, I just sort of gave up. I knew I would end up back in the hospital (age 62, Female, Uninsured).” This perceived failure caused patients to disengage further from their healthcare providers: “Well, what’s the use of seeing [my doctor] if I’m not doing the right thing? He’s done his best but I’m not doing my best (age 44, Female, Dually eligible).”

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study of low-SES, hospitalized patients, we observed a number of key issues that are likely to impact post-hospital outcomes. During hospitalization, many patients were conscious of their underinsurance and socioeconomic status, which heightened the patient-provider power differential. Patients described a sense of disconnect with providers, whom patients felt could not relate to the socioeconomic issues they faced outside of the hospital. As a result of this disconnect, the care team set discharge goals that were unrealistic, confusing, or simply not salient for patients who were struggling with larger issues. After leaving the hospital, patients did in fact have difficulty performing discharge instructions, often because they could not afford recommended medications or care. At this critical juncture, patients felt abandoned by health system and social supports. Patients explained that this combination of misaligned goals, external constraints and lack of support made it much more likely they would fail in carrying out recommended health behaviors. This failure undermined patients’ self-confidence and led them to disengage from future health behaviors.

Our findings underscore the challenges faced by low-SES patients during the transition from hospital to home. A key event in the post-hospital course occurs when the team sets discharge goals that are confusing, unrealistic or in conflict with patients’ own goals. Patients are often unable to discuss and negotiate these misaligned goals due to the rapidity of discharge, limited health literacy, and communication barriers with providers. When it becomes clear that competing life issues and financial or social barriers will undermine patients’ ability to perform recommended behaviors, the resulting failure leads to low self-efficacy, which may cause poor performance on other complex health behaviors. This places patients even further apart from providers at the next goal-setting episode, perpetuating the cycle. This pattern is consistent with a “negative goal cycle,” (Fig. 1) adapted from Locke’s30–32 goal-setting theory, which suggests that goals usually lead to improved performance because they enhance concentration, effort and persistence.32 However, there are several conditions—namely the setting of unattainable, confusing or conflicting goals—in which goal-setting may not enhance performance and in fact may be deleterious.”27,33–38

Negative goal cycle. Low-SES patients are “set up for failure” to achieve discharge goals that are misaligned because they are confusing, unattainable or in conflict with other more pressing goals. The resulting failure leads to low self-efficacy, which may lead to poor performance on other complex health behaviors. This may place the low-SES patient even further apart from the provider at the next goal-setting episode, making it more likely that the next set of goals are misaligned and the cycle is perpetuated.

Our results suggest that the negative goal-cycle may serve as a theoretical framework for understanding the poor post-hospital outcomes observed among low-SES patients. This theory is consistent with findings from prior studies of hospitalized patients emphasizing discharge communication and sustained health system support to counter-balance the difficulties of self-care after hospitalization. This study also allows low-SES patients to describe, in their own words, the challenges that may underlie non-adherence. This knowledge may prevent providers from setting unrealistic goals or assigning blame to patients for poor adherence or outcomes (fundamental attribution error).39

Our findings have implications for policies and efforts designed to improve post-hospital outcomes. This study uncovers several ways in which hospitals might improve the care they provide for low-SES patients. For instance, this study raises the question of whether collaborative goal-setting, the process by which provider and patient agree on a set of realistic and meaningful discharge goals, may lead to higher levels of health behavior performance, improved self-efficacy and better outcomes. Additional research exploring the relationships between collaborative goal-setting, self-efficacy and outcomes among low-SES patients would help answer this question and inform the design of interventions for the post-hospital transition. Our findings also suggest that while the Medicare readmissions penalty may have some unintended consequences, CMS was justified in not allowing hospitals to adjust away disparities. Rather, the penalty may incentivize hospitals to provide care that is centered towards the needs and goals of the low-SES patient.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a qualitative study designed to explore, rather than test, hypotheses. The proposed conceptual framework may be an incorrect interpretation of study findings and requires testing by additional prospective studies. Second, this is a single-center study; therefore, the perspectives described may not be generalizable beyond an urban, poor and predominantly African American patient population. Thirdly, our interviews focused on the patient and caregiver perspective; additional qualitative research on goal-setting might make use of patient-provider dyads in order to more deeply explore reasons for misalignment. Finally, we are unable to draw conclusions about whether our findings are unique to low-SES patients because we did not interview high-SES patients for comparison.

For both ethical and financial reasons, it will be crucial for hospitals to address socioeconomic disparities in post-hospital outcomes. While it is not possible for hospital providers to address the innumerable challenges that low-SES patients face outside of the hospital, they may be able to engage low-SES patients in the process of setting achievable, meaningful discharge goals that may create a positive cycle of achievement, self-efficacy and improved health outcomes.

REFERENCES

Bradbury RC, Golec JH, Steen PM. Comparing uninsured and privately insured hospital patients: admission severity, health outcomes and resource use. Health Serv Manag Res. 2001;14(3):203–10 [Comparative Study].

Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S, Roberts M, Moloney TW, McMullen W, Walker JD, et al. Patients evaluate their hospital care: a national survey. Health Aff (Millwood). 1991;10(4):254–67 [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Epstein AM, Stern RS, Tognetti J, Begg CB, Hartley RM, Cumella E Jr, et al. The association of patients’ socioeconomic characteristics with the length of hospital stay and hospital charges within diagnosis-related groups. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(24):1579–85 [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Kangovi S, Grande D, Grande, Meehan P, Mitra N, Shannon R, Long JA. Perceptions of Readmitted Patients on the Transition from Hospital to Home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–12.

Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392–7.

Asplin BR, Rhodes KV, Levy H, Lurie N, Crain AL, Carlin BP, et al. Insurance status and access to urgent ambulatory care follow-up appointments. Jama. 2005;294(10):1248–54 [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.].

Forsythe S, Chetty VK) if correct.?>Forsythe S, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Johnson A, Greenwald J, Paasche-Orlow M, editor. Risk score to predict readmission after discharge. The North American Primary Care Research Group Conference; 2006 Oct 15–18; Tucson, AZ.

Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Scott T, Parker RM, Green D, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1278–83 [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Elixhauser A, Au DH, Podulka J. Readmissions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2008: Statistical Brief #121. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD)September 2011.

Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillon P, Herrera MC, Otero CM, Chiva MO, Ochoa CC, et al. Social network as a predictor of hospital readmission and mortality among older patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12(8):621–7 [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Foraker RE, Rose KM, Suchindran CM, Chang PP, McNeill AM, Rosamond WD. Socioeconomic status, medicaid coverage, clinical comorbidity, and rehospitalization or death after an incident heart failure hospitalization: atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort (1987 to 2004). Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):308–16 [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural].

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, Affordable Care Act Section 3025. 2012 Inpatient Prospective Payment System Final Rule, 2012.

Kangovi S, Grande D. Hospital readmissions–not just a measure of quality. Jama. 2011;306(16):1796–7.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e02.

Weaver FM, Perloff L, Waters T. Patients’ and caregivers’ transition from hospital to home: needs and recommendations. Home Health Care Serv Q. 1998;17(3):27–48 [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Armitage SK, Kavanagh KM. Consumer-orientated outcomes in discharge planning: a pilot study. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7(1):67–74.

Coffey A, McCarthy GM. Older people’s perception of their readiness for discharge and postdischarge use of community support and services. Int J Older People Nurs. 2013;8(2):104–15.

Cain CH, Neuwirth E, Bellows J, Zuber C, Green J. Patient experiences of transitioning from hospital to home: an ethnographic quality improvement project. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):382–7.

Vom Eigen KA, Walker JD, Edgman-Levitan S, Cleary PD, Delbanco TL. Carepartner experiences with hospital care. Med Care. 1999;37(1):33–8 [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.].

Retrum JH, Boggs J, Hersh A, Wright L, Main DS, Magid DJ, et al. Patient-identified factors related to heart failure readmissions. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(2):171–7.

Annema C, Luttik ML, Jaarsma T. Reasons for readmission in heart failure: perspectives of patients, caregivers, cardiologists, and heart failure nurses. Heart Lung. 2009;38(5):427–34 [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Strunin L, Stone M, Jack B. Understanding rehospitalization risk: can hospital discharge be modified to reduce recurrent hospitalization? J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):297–304 [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.].

Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean LT, Micco E, Putt M, Halbert CH, et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):827–33 [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH Jr, Shaker L. Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8):896–901 [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural].

Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273–302 [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.].

Brickner PW, Scanlan BC, Conanan B, Elvy A, McAdam J, Scharer LK, et al. Homeless persons and health care. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104(3):405–9 [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review].

Bandura A. Fearful expectations and avoidant actions as coeffects of perceived self-inefficacy. Am Psychol. 1986;41(12):1389–91.

Bandura A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1986;4(3):359–73.

Bandura A. From thought to action - mechanisms of personal agency. New Zeal J Psychol. 1986;15(1):1–17.

Locke EA, Latham GP. A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1990.

Latham GP, Locke EA, Fassina NE. The high performance cycle: Standing the test of time. In: Sonnentag S, ed. Psychological management of individual performance. Chichester: Wiley; 2002.

Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57(9):705–17.

Stretcher VJSG, Kok GJ, Latham GP, Glasgow R, DeVellis B, et al. Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1995;22:190–200.

Cervone D, Jiwani N, Wood R. Goal-setting and the differential influence of self-regulatory processes on complex decision-making performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(2):257–66.

Erez M, Kanfer FH. The role of goal acceptance in goal setting and task performance. Acad Manag Rev. 1983;8(3):454–63.

Kanfer R, Ackerman PL. Motivation and cognitive-abilities - an integrative aptitude treatment interaction approach to skill acquisition. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(4):657–90.

Earley PC, Connolly T, Ekegren G. Goals, strategy development and task performance: some limits on the efficacy of goal setting. J Appl Pyschol. 1989;74:24–33.

Hospers HJ, Kok G, Strecher VJ. Attributions for previous failures and subsequent outcomes in a weight reduction program. Heal Educ Q. 1990;17(4):409–15.

Heider F. The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley; 1958.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Grande has received honoraria from the Johns Hopkins University CME Program, had a consultancy with the National Nursing Centers Consortium and has received grant support from or has grants pending with the HealthWell Foundation, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kangovi, S., Barg, F.K., Carter, T. et al. Challenges Faced by Patients with Low Socioeconomic Status During the Post-Hospital Transition. J GEN INTERN MED 29, 283–289 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2571-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2571-5