ABSTRACT

When studying the patient perspective on communication, some studies rely on analogue patients (patients and healthy subjects) who rate videotaped medical consultations while putting themselves in the shoes of the video-patient. To describe the rationales, methodology, and outcomes of studies using video-vignette designs in which videotaped medical consultations are watched and judged by analogue patients. Pubmed, Embase, Psychinfo and CINAHL databases were systematically searched up to February 2012. Data was extracted on: study characteristics and quality, design, rationales, internal and external validity, limitations and analogue patients’ perceptions of studied communication. A meta-analysis was conducted on the distribution of analogue patients’ evaluations of communication. Thirty-four studies were included, comprising both scripted and clinical studies, of average-to-superior quality. Studies provided unspecific, ethical as well as methodological rationales for conducting video-vignette studies with analogue patients. Scripted studies provided the most specific methodological rationales and tried the most to increase and test internal validity (e.g. by performing manipulation checks) and external validity (e.g. by determining identification with video-patient). Analogue patients’ perceptions of communication largely overlap with clinical patients’ perceptions. The meta-analysis revealed that analogue patients’ evaluations of practitioners’ communication are not subject to ceiling effects. Analogue patients’ evaluations of communication equaled clinical patients’ perceptions, while overcoming ceiling effects. This implies that analogue patients can be included as proxies for clinical patients in studies on communication, taken some described precautions into account. Insights from this review may ease decisions about including analogue patients in video-vignette studies, improve the quality of these studies and increase knowledge on communication from the patient perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTIONS

Studies of the patient perspective on communication usually rely on clinical patients (CPs) who rate their practitioner’s communication.1,2 Other studies rely on analogue patients (APs)—patients and/or healthy subjects—who rate videotaped medical consultations while putting themselves in the shoes of the video-patient. These videotapes can be of real encounters (referred to as ‘clinical studies’) or scripted encounters (referred to as ‘scripted studies’). Scripted studies provide researchers the opportunity to vary and study specific elements of communication (e.g. compassionate remarks).3

Until now, insight into the reasons warranting the use of video-vignette studies with APs is lacking. Studies might use general, implicit rationales. Alternatively, there may be ethical considerations; not all communication can cautiousness be randomized in clinical care. Methodological advantages may be another reason. As stated above, scripted studies can investigate specific elements of communication. Additionally, CPs are often extremely satisfied with their practitioner4,5—perhaps because they feel dependent6 or because of social desirability7—leading to ceiling effects. It has to be established whether APs’ evaluations of communication can overcome ceiling effects, and which rationales underlie and strengthen the use of video-vignette studies.

While video-vignette studies are sometimes preferred over empirical studies, the former may have validity problems. With regard to internal validity in scripted studies, the question arises whether manipulations are successful, i.e. variations in empathy should be perceived as such. With regard to external validity, the question arises whether results are generalizable to CPs and clinical care, i.e. are APs able to adopt a video-patient’s perspective?

Considerable research has been conducted on how CPs perceive their doctor’s communication. CPs appreciate various types of affective communication: verbal empathy,8–10 social talk,8–11 non-verbal eye-contact8 and listening.8,10 Appreciated instrumental communication includes information-giving.8–12 Last, ‘patient-centeredness’ is an often studied ‘general’ communication style mostly associated with positive outcomes.8–15 Whether APs evaluate these communication elements similarly is largely unknown.

To summarize, we lack an understanding of the rationales for conducting video-vignette studies with APs; how both internal and external validity are increased and tested; how APs’ perceptions of communication correspond to CPs’ perceptions; and whether APs’ evaluations of communication overcome ceiling effects. An overview of these elements will provide more insight into when and how APs can be used in future studies. Therefore, a systematic review is conducted with the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the rationales for conducting clinical and scripted video-vignette studies on medical communication with APs ?

-

2.

What have video-vignette studies done to increase and test their internal and external validity?

-

3.

How do APs perceive—affective, instrumental and general—communication elements?

-

4.

Do APs’ evaluations of communication overcome ceiling effects?

METHODS

Identification of Studies

Pubmed, Embase, Psycinfo and CINAHL were searched in February 2012. Searches were not restricted to any parameter and focused on two central concepts: ‘analogue patients’ and ‘video’ (see the Online Appendix Supplementary data for search strategies used).

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were about (verbal/nonverbal) communication between physicians/nurses and patients and: i) used video-vignette designs; ii) included APs (>18 years): healthy subjects, untrained or trained only for this study; patients not judging their own doctor/nurse; standardized patients viewing a videotaped consultation they took part in; and iii) used APs’ perceptions of physician’s/nurse’s communication as outcome measures (e.g., preferences, recall). Studies were excluded if: i) observers were trainers, research assistants, trained/experienced coders, examiners, medical students or faculty members; ii) APs’ comments did not include a quality judgment.

Data

The following data were extracted from each study and summarized in Table 1: study characteristics and quality, design, rationales for conducting video-vignette studies with APs, attempts to increase and test internal and external validity, limitations, and APs’ perceptions of the studied communication elements.

Quality of studies was assessed16 by applying the Research Appraisal Checklist (RAC).17 The RAC consists of 51 items covering the quality of title, abstract, introduction, methodology, data analysis, discussion, and style/form. Each item is scored on a 1–6 scale, so total scores can vary between 0 and 306 points with three quality categories: i) Below Average (0–103 points), ii) Average (103–204 points), iii) Superior (205–306 points).

Meta-Analysis to Determine Ceiling Effects

To determine whether APs’ evaluations of communication (e.g. satisfaction, preferences) overcome ceiling effects, a random-effects multivariate meta-regression analysis18 was performed using the statistical package MLWIN 2.02.19 The following quantitative data was abstracted for each evaluation: M, SD, range. For each study the number of participants, videos viewed per participant and available videos was abstracted. For each evaluation, using various scales, the mean score was transformed to a 0–100 score20 using two formulas; for scales starting at 1: ((mean-1)/(range-1))x100, for scales starting at 0: ((mean/range))x100. Authors were contacted to provide relevant data not presented in the articles.

RESULTS

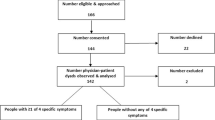

The 2950 references initially found were reviewed on title/abstract (and if necessary on full-text) to determine whether they: a) were about communication, b) used a video-vignette design, c) included APs. A random 10 % of the articles were independently checked on these criteria by two authors (LV and JB); interrater agreement exceeded 95 %. Thirty-four articles met these criteria and a forward- and backward reference search was performed. Four hundred and fifty-two new articles were reviewed in the aforementioned manner, resulting in 32 additional articles. These 66 articles were explored full-text on the final criteria: a) a focus on doctor/nurse-patient communication, b) inclusion of APs who viewed videos and judged the communication. Thirty-four articles met all criteria. Their references were hand-searched, resulting in four extra articles. Accordingly, 38 articles were included (see Fig. 1) that were based on 34 studies; some studies produced multiple articles.21–28

Description of Included Studies

Study Characteristics and Quality

All studies were published in English, between 1982 and 2012, and conducted in the USA3,21–26,29–48 (n = 24), Switzerland27,28,49,50 (n = 3), UK51–54 (n = 4), Australia55,56 (n = 2), and an European setting.57 Studies were performed in general care 21–31,33–43,48,50,51,54,55,57 (n = 25), oncology3,32,47,49,56 (n = 5), psychiatry46,52,53 (n = 3), and genetic counseling.45

Most studies included lay people 21,22,29,31–36,39,42,45,46,51,55–57 (n = 16)—who were trained in two studies36,46—or non-medical students 23–28,30,34,37,38,41,43,44,48–50 (n = 13). Some studies included cancer survivors3,47 (n = 2) or patients with/at risk of coronary heart disease (CAD).40 In three studies standardized patients viewed videotaped consultations they had participated in.52–54

As determined with the RAC, 8 studies25,26,31,35,37,39,46,52,53 were of average quality, the remaining of superior quality. Four articles (10 %) were independently rated by two authors (LV and AA); the quality category was agreed on. Differences in quality assessment for specific items were resolved by consensus. The studies of average quality mostly lacked quality in the areas of methodology (e.g. design) and introduction (e.g. problem definition).

Study Design

Eighteen studies were clinical.23–28,30–32,36,37,39,41,44–46,50,52–54,57 These included videos with standardized 23–26,30–32,39,41,44–46,52–54,57 (n = 14) or clinical27,28,36,37,50 (n = 4) patients. Sixteen studies were scripted;3,21,22,29,33–35,38,40,42,43,47–49,51,55,56 APs watched one3,29,35,40,42,43,47–49,55 (n = 10) or multiple21,22,33,34,38,51,56 (n = 6) videos. Six studies21,22,32,34,39,51,54 had a (partially) qualitative approach. Physicians’ communication was most often assessed 3,21,22,25–35,37–44,46–57 (n = 31), but some studies included nurses23,24,36 (n = 2) or genetic counselors.45

Rationales for Conducting Video-Vignette Studies with APs

Twenty-one studies reported general, ethical or methodological rationales for conducting video-vignette studies with APs.21,22,25–31,33,35,40–43,46–50,54–57 According to general rationales, APs are representative for CPs.25–28,30,33,41,46,50,57 Scripted studies pointed out the ethical constraints of standardizing (negative) communication in real consultations.47,48 When providing methodological rationales authors argued that; ceiling effects may be overcome;21,22,40,56 reliability increases with multiple raters;31 scripted studies increase internal validity42 and investigate communication systematically;21,22,29,33,35,40,43,55,56 clinical studies can standardize physicians27,28,33,41,50,57 and assess the influence of background characteristics.50,57 One study included healthy subjects because including patients would be unethical and patients may be distracted by their own memories.49

Validity

Internal Validity

All but one38 of the scripted studies tried to achieve internal validity by ensuring that their manipulations were successful. APs40,55,56 and experts21,22,40,47,55,56 were involved in creating the scripts, or content from clinical interactions was used.3,48 Furthermore, APs29,35,42,43,47,48,51,55,56 or experts21,22,34 concluded that communication varied between videos (manipulation check), but only three studies provided useful numerical data.35,47,48 Other studies objectively coded the studied communication in their videos.25,26,30,41,49,50,57

External Validity

In attempt to ensure external validity several (oncological) scripted studies focused on APs’ identification with the video-patient. Three studies measured (and ensured) the level of identification.47,49,55 Other studies included subjects at risk of developing cancer47 or CAD,40 included CAD patients,40 or included both healthy participants and cancer survivors;3,56 their perceptions overlapped and were merged for analyses. Other (non-oncological) scripted studies tried to increase APs’ identification in various ways; by depicting only the physician;29,38,40,42 decreasing patient dialogue;29,42 introducing the patient (via text or video);40,47,55 asking participants to remember the time they visited the doctor with a similar health problem;48 using personalized questions;35 and recruiting participants waiting for a doctor’s appointment.21,22,29,35,40,42,51

Furthermore, scripted studies often focused on video credibility to ensure external validity; APs stated that the videos were credible,3,29,42,43,47,48,55 while only five studies provided numerical data.29,42,47,48,55 Indirect evidence for external validity was provided by clinical and scripted studies stating that: APs are potential patients;27,28 differences in APs’ preferences equal those of CPs;21,22 and simulated and clinical situations evoke equal reactions.55 Last, one clinical study46 assessed external validity, i.e. medical students who were appreciated by APs reported more satisfying interactions with CPs.

Twenty-three studies mentioned generalizability as limitation.3,21–30,34,35,40–45,47–50,54–57 It was often questioned whether APs’ reactions equal CPs’ reactions3,21–26,29,34,35,42–45,49,50,54,57 and whether findings were generalizable to real—interactive—consultations23,24,30,40–43,47,54 or other participants (e.g. demographic characteristics).23,24,27,28,41,45,49,50,55–57 Research with CPs in real consultations was often recommended.23–26,30,34,41,44,48,49,54,55

Perceptions of Communication

APs’ perceptions of communication were studied. Patient-centeredness was preferred overall to doctor-centeredness,21,22,33,34,40,41,49,56 but not for acute physical problems.51 (Non)verbal affective communication was overall associated with positive effects (on trust,29,43 satisfaction,29,43,48,55,57 anxiety-reduction,3,47 intended self-disclosure43), but inconsistent results were found on intended compliance43,48,55 and recall.3,29,47,55 Social talk was appreciated in general care,34 but not during bad news conversations.44 Appreciated nonverbal behaviors included; rapport,25,26 listening,23,24 (non)verbal gender-congruent behavior,27,28 affiliativeness,50 an open body posture combined with nodding,38 concernedness,42 while the effect of nonverbal sensitivity was inconsistent.26,45 Two studies36,37 compared APs’ perceptions with videotaped patients’ satisfaction of nonverbal behavior; one study36 found a positive relation. Instrumental communication produced mixed results. In general care, information provision31,39,54 and little expression of uncertainty30,35 were appreciated, while the effect of competence was inconsistent.29,48 Conversely, during bad news consultations information-exchange was negatively evaluated.44

Ceiling Effects

A random-effects multivariate meta-regression model compared the transformed means of 64 evaluations for 20 studies.3,21–24,27,28,30,31,35–37,40–43,49,50,55,57 The overall mean of APs’ evaluations was 54.28 on a 0–100 scale, 95 % CI: 47.99–60.57. (Single) mean evaluations varied between 24.00 and 82.00 while studies’ mean evaluations varied between 39.30 and 69.26, indicating also that no plateau effect occurred.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review focused on the rationales, methodology and outcomes of medical video-vignette studies with APs. Scripted studies provided more specific rationales for using video-vignette designs with APs than clinical studies and directed more efforts at increasing/testing internal and external validity. APs’ perceptions of communication overlapped generally with CPs’ perceptions. Meanwhile, their evaluations overcame ceiling effects. These results have interesting methodological, theoretical and practical relevance.

Scripted studies paid the most attention to increasing the designs’ methodological soundness. Specific methodological rationales for conducting video-vignette studies with APs were provided, such as the opportunity to study communication systematically. This fills a gap in clinical care studies, in which only correlations, but no causality between communication and outcomes can be determined.58,59 Unfortunately, some scripted studies included container-concepts of communication (e.g., patient-centeredness). When positive effects are found, it remains unclear which specific element(s) of communication influenced outcomes.15,58 Additionally, as argued, when videos are watched by multiple APs, the reliability of assessments increases.60,61

Another argument for including APs was that their evaluations can overcome ceiling effects. APs’ evaluations were indeed not high; averagely 54.28 on a 0–100 scale. By comparison, a meta-analysis of CPs’ satisfaction ratings showed an average score of 80.00 (0–100 scale).20 Moreover, a recent study compared CPs’ satisfaction scores with those of APs viewing these videotaped consultations. Mean score (1–6 scale) for CPs was 5.8, while for APs it was 4.0 (p < 0.001).62 APs’ ratings thus seem to overcome this limitation of CPs’ evaluations.4,5 Accordingly, these and other methodological rationales provide strong foundations for conducting video-vignette studies with APs.

To achieve internal validity, APs reflected on manipulations in scripted consultations. Unexpectedly, ‘experts’ (doctors/researchers) were not often asked to comment on manipulations, although they may have insight into the manipulations’ (theoretical) success. Moreover, little information was provided on how exactly scripts were created, i.e. it often remained unclear what input researchers used to develop scripts and at what point(s) the scripts were validated.

Focusing on external validity, some studies argued that APs’ perceptions overlap with CPs’ perceptions. However, none of these studies determined whether APs watching videotaped consultations and CPs in these consultations overlapped on outcome measures. As stated earlier, such a study has recently been performed.62 In this study—taking into account CPs’ skewed satisfaction scores—APs’ and CPs’ evaluations were correlated. Additionally, a meta-analysis in psychology63 showed that lay people can make reliable judgments for (non)verbal communication based on brief (clinical and scripted) videotaped interactions.

Theoretical evidence supporting the external validity of APs can be found in simulation theory and is supported by neuro-cognitive studies on empathy. According to simulation theory, we infer other persons’ mental states by matching their states with resonant states of one’s own mental state.64 Neuro-cognitive studies show that the brain’s mirror neurons fire when a particular action is carried out or observed.65 They form the basis for empathy,66–69 as they are involved in experiencing and observing emotions in others70 and allow people to adopt another person’s perspective.71 Indeed, some oncological scripted studies included survivors alongside healthy participants. Their perceptions overlapped, indicating that healthy people can put themselves in the shoes of (cancer) patients.72

However, the methodological and theoretical rationales and advantages of using APs as proxies for CPs are relevant only when APs’ perceptions of communication are applicable in clinical practice, which is mainly supported by our results. APs’ perceptions of communication overlap mostly with those of CPs. A few—seemingly—contradictory findings were found. APs disliked information-exchange during bad news conversations, while CPs mostly valued this behavior. However, CPs often report receiving too much information during these conversations.73–78 Besides, while most studies point to the positive effects of patient-centeredness, a study with APs51 and review on CPs12 found that for purely physical complaints, a patient-centered style may be suboptimal.

Despite these promising results, various aspects should be taken into account when interpreting APs’ perceptions for clinical practice. First, in one study APs’ perceptions were unrelated to CPs’ satisfaction scores. The considerable age difference (students versus seniors) may be responsible for this finding, as age influences communication preferences.79–81 Future studies should take background characteristics influencing preferences—e.g. gender,81,82 education83,84—into account. Consequently, students should not be included as APs merely for convenience. Second, the diversity in APs’ evaluations should be kept in mind. The long-term doctor–patient relationship possibly influencing CPs’ evaluations cannot be captured by studies using APs. Thus, as video-vignette studies make it possible to disentangle the effect of various communication elements, these elements should afterwards be tested in clinical care.

Limitations

This review has its limitations. First, the literature is inconsistent in the terms used for “analogue patients”. To include all relevant articles, both forward and backward reference searches on possible relevant articles were performed and included studies’ references were hand-searched. Future studies should use the term “analogue patients” consistently. Second, we excluded trained observers, but included lay people trained for this specific study. As studies may have used inconsistent labels, we screened for detailed information on observers. Despite these precautions taken, inadequately indexed and little cited relevant studies may have been missed, as we used a top-down search strategy.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE STUDIES

Scripted video-vignette studies increased their methodological soundness by providing specific rationales for conducting video-vignette studies with APs and increasing (internal and external) validity. In keeping with simulation theory and neuro-cognitive studies, APs’ perceptions of communication overlapped largely with CPs’ perceptions—while overcoming ceiling effects. However, it may be necessary to match participants on variables such as age and gender. Moreover, the effect of a long-term doctor–patient relationship on evaluations cannot be studied with APs. This leads to the conclusion—taking these precautions into account—that APs can provide knowledge on the patient perspective on communication.

Future—scripted—studies may benefit from the described elements to increase their methodological strength and provide more information about the process of ensuring validity. From this review we cannot conclude which communication elements—and outcome measures—can best be studied with APs. Ambady and Rosenthal63 suggested that communication with an affective component is fastest recognized because its evolutionary importance.85,86 Future studies could investigate differences between various types of APs. Research could build further on aforementioned work,62 comparing CPs’ perceptions with those from APs watching these consultations, taking into account differences in rating dispersion and focusing on background characteristics. This will raise the level of future studies in this promising research field, aimed at systematically unraveling the patient perspective on communication.

References

Ptacek JT, Ptacek JJ. Patients' perceptions of receiving bad news about cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4160–4.

Schofield PE, Butow PN, Thompson JF, Tattersall MH, Beeney LJ, Dunn SM. Psychological responses of patients receiving a diagnosis of cancer. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:48–56.

Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–9.

Sitzia J. How valid and reliable are patient satisfaction data? An analysis of 195 studies. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999;11:319–28.

Rosenthal GE, Shannon SE. The use of patient perceptions in the evaluation of health-care delivery systems. Med Care. 1997;35(Suppl):NS58–68.

Brown R, Dunn S, Butow P. Meeting patient expectations in the cancer consultation. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:877–82.

Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1516–28.

Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: A systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:25–38.

Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–33.

Hack TF, Degner LF, Parker PA, SCRN Communication Team. The communication goals and needs of cancer patients: A review. Psycho-oncol. 2005;14:831–45.

Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–75.

Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor–patient communication and patient satisfaction: A review. Fam Pract. 1998;15:480–92.

Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor–patient communication: A review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:903–18.

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: A review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:51–61.

Epstein RM, Street RLJ. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 07-6225. Bethesda, MD, 2007.

Moja LP, Telaro E, D'Amico R, Moschetti I, Coe L, Liberati A. Assessment of methodological quality of primary studies by systematic reviews: Results of the metaquality cross sectional study. BMJ. 2005;330:1053–7.

Duffy ME. Research appraisal checklist. In: Waltz C, Jenkins L, eds. Measurement of Nursing Outcomes. Vol 1: Measuring Nursing Performance in Practice, Education an Research. New York: Springer; 2001:323–30.

Hox J. Multilevel Analysis. Techniques and Applications. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2010.

Rasbash J, Charlton C, Browne WJ, Healy M, Cameron B. WLwiN Verson 2.02. University of Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling; 2005.

Hall JA, Dornan MC. Meta-analysis of satisfaction with medical care: Description of research domain and analysis of overall satisfaction levels. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:637–44.

Swenson SL, Zettler P, Lo B. 'She gave it her best shot right away': Patient experiences of biomedical and patient-centered communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:200–11.

Swenson SL, Buell S, Zettler P, White M, Ruston DC, Lo B. Patient-centered communication: Do patients really prefer it? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1069–79.

Gilbert DA. Relational message themes in nurses' listening behavior during brief patient-nurse interactions. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1998;12:5–21.

Gilbert DA. Coordination in nurses' listening activities and communication about patient-nurse relationships. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:447–57.

Hall JA, Roter DL, Blanch DC, Frankel RM. Observer-rated rapport in interactions between medical students and standardized patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:323–7.

Hall JA, Roter DL, Blanch DC, Frankel RM. Nonverbal sensitivity in medical students: Implications for clinical interactions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1217–22.

Schmid Mast M, Hall JA, Cronauer CK, Cousin G. Perceived dominance in physicians: Are female physicians under scrutiny? Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:174–9.

Mast MS, Hall JA, Kockner C, Choi E. Physician gender affects how physician nonverbal behavior is related to patient satisfaction. Med Care. 2008;46:1212–8.

Roberts CA, Aruguete MS. Task and socioemotional behaviors of physicians: A test of reciprocity and social interaction theories in analogue physician-patient encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:309–15.

Blanch DC, Hall JA, Roter DL, Frankel RM. Is it good to express uncertainty to a patient? Correlates and consequences for medical students in a standardized patient visit. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:300–6.

Mazor KM, Ockene JK, Rogers HJ, Carlin MM, Quirk ME. The relationship between checklist scores on a communication OSCE and analogue patients' perceptions of communication. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2005;10:37–51.

Quirk M, Mazor K, Haley HL, et al. How patients perceive a doctor's caring attitude. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:359–66.

Gerbert B, Berg-Smith S, Mancuso M, et al. Video study of physician selection: Preferences in the face of diversity. J Fam Pract. 2003;52:552–9.

Floyd M, Lang F, Beine KL, McCord E. Evaluating interviewing techniques for the sexual practices history. Use of video trigger tapes to assess patient comfort. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:218–23.

Johnson CG, Levenkron JC, Suchman AL, Manchester R. Does physician uncertainty affect patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:144–9.

Haskard KB, DiMatteo MR, Heritage J. Affective and instrumental communication in primary care interactions: Predicting the satisfaction of nursing staff and patients. Health Commun. 2009;24:21–32.

Koss T, Rosenthal R. Interactional synchrony, positivity, and patient satisfaction in the physician-patient relationship. Med Care. 1997;35:1158–63.

Harrigan JA, Rosenthal R. Physicians' head and body positions as determinants of perceived rapport. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1983;13:496–509.

Mazor KM, Zanetti ML, Alper EJ, et al. Assessing professionalism in the context of an objective structured clinical examination: An in-depth study of the rating process. Med Educ. 2007;41:331–40.

Saha S, Beach MC. The impact of patient-centered communication on patients' decision making and evaluations of physicians: A randomized study using video vignettes. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:386–92.

Blanch-Hartigan D, Hall JA, Roter DL, Frankel RM. Gender bias in patients' perceptions of patient-centered behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:315–20.

Aruguete MS, Roberts CA. Participants' ratings of male physicians who vary in race and communication style. Psychol Rep. 2002;91:793–806.

Aruguete SM, Roberts CA. Gender, affiliation, and control in physician-patient encounters. Sex Roles. 2000;42:107–18.

Gillotti C, Thompson T, McNeilis K. Communicative competence in the delivery of bad news. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1011–23.

Roter DL, Erby LH, Hall JA, Larson S, Ellington L, Dudley W. Nonverbal sensitivity: Consequences for learning and satisfaction in genetic counseling. Health Educ. 2008;198:397–410.

Mumford E, Schlesinger H, Cuerdon T, Scully J. Ratings of videotaped simulated patient interviews and four other methods of evaluating a psychiatry clerkship. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:316–22.

Shapiro DE, Boggs SR, Melamed BG, Graham-Pole J. The effect of varied physician affect on recall, anxiety, and perceptions in women at risk for breast cancer: An analogue study. Health Psychol. 1992;11:61–6.

Willson P, McNamara JR. How perceptions of a simulated physician-patient interaction influence intended satisfaction and compliance. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:1699–704.

Schmid Mast M, Kindlimann A, Langewitz W. Recipients' perspective on breaking bad news: How you put it really makes a difference. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58:244–51.

Cousin G, Schmid Mast M. Agreeable patient meets affiliative physician: How physician behavior affects patient outcomes depends on patient personality. Patient Educ Couns. 2011; doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.010.

McKinstry B. Do patients wish to be involved in decision making in the consultation? A cross sectional survey with video vignettes. BMJ. 2000;321:867–71.

Kaaya S, Goldberg D, Gask L. Management of somatic presentations of psychiatric illness in general medical settings: Evaluation of a new training course for general practitioners. Med Educ. 1992;26:138–44.

Gask L, Goldberg D, Porter R, Creed F. The treatment of somatization: Evaluation of a teaching package with general practice trainees. J Psychosom Res. 1989;33:697–703.

Quilligan S, Silverman J. The skill of summary in clinician-patient communication: A case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:354–9.

Bradley G, Sparks B, Nesdale D. Doctor communication style and patient outcomes: Gender and age as moderators. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2001;31:1749–73.

Dowsett SM, Saul JL, Butow PN, et al. Communication styles in the cancer consultation: Preferences for a patient-centred approach. Psycho-Oncol. 2000;9:147–56.

Mazzi MA, Bensing J, Rimondini M, et al. How do lay people assess the quality of physicians' communicative responses to patients' emotional cues and concerns? An international multicentre study based on videotaped medical consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2011. Epub ahead of print.

de Haes H, Bensing J. Endpoints in medical communication research, proposing a framework of functions and outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:287–94.

Hall JA. Some observations on provider-patient communication research. Patient Educ Couns 2003;30:9–12.

Wensing M, van de Vleuten C, Grol R, Felling A. The reliability of patients' judgements of care in general practice: How many questions and patients are needed? Qual Health Care. 1997;6:80–5.

Woolliscroft JO, Howell JD, Patel BP, Swanson DB. Resident-patient interactions: The humanistic qualities of internal medicine residents assessed by patients, attending physicians, program supervisors, and nurses. Acad Med. 1994;69:216–24.

Blanch-Hartigan D, Hall JA, Krupat E, Irish JT. Can naive viewers put themselves in the patients' shoes? Reliability and validity of the analog patient methodology. Med Care. 2012; Epub ahead of print.

Ambady N, Rosenthal R. Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:256–74.

Gallese V. Before and below 'theory of mind': Embodied simulation and the neural correlates of social cognition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362:659–69.

Rizzolatti G, Fadiga L, Gallese V, Fogassi L. Premotor cortex and the recognition of motor actions. Cognit Brain Res. 1996;3:131–41.

Singer T, Seymour B, O'Doherty J, Kaube H, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303:1157–62.

Avenanti A, Bueti D, Galati G, Aglioti SM. Transcranial magnetic stimulation highlights the sensorimotor side of empathy for pain. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:955–60.

Wicker B, Keysers C, Plailly J, Royet JP, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G. Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron. 2003;40:655–64.

Leslie KR, Johnson-Frey SH, Grafton ST. Functional imaging of face and hand imitation: Towards a motor theory of empathy. Neuroimage. 2004;21:601–7.

Gallese V, Keysers C, Rizzolatti G. A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:396–403.

Rizzolatti G, Sinigaglia C. The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: Interpretations and misinterpretations. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:264–74.

van Vliet L, Francke A, Tomson S, Plum N, van der Wall E, Bensing J. When cure is no option: How explicit and hopeful can information be given? A qualitative study in breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2011. Epub ahead of print.

Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. When and how to initiate discussion about prognosis and end-of-life issues with terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:132–44.

Kirk P, Kirk I, Kristjanson LJ. What do patients receiving palliative care for cancer and their families want to be told? A Canadian and Australian qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328:1343–51.

Butow PN, Dowsett S, Hagerty R, Tattersall MH. Communicating prognosis to patients with metastatic disease: What do they really want to know? Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:161–8.

Benson J, Britten N. Respecting the autonomy of cancer patients when talking with their families: Qualitative analysis of semistructured interviews with patients. BMJ. 1996;313:729–31.

Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moynihan C, et al. Faith, hope, and charity: An in-depth interview study of cancer patients' information needs and information-seeking behavior. West J Med. 2000;173:26–31.

Elkin EB, Kim SH, Casper ES, Kissane DW, Schrag D. Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: Elderly cancer patients' preferences and their physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5275–80.

Krupat E, Rosenkranz SL, Yeager CM, Barnard K, Putnam SM, Inui TS. The practice orientations of physicians and patients: The effect of doctor–patient congruence on satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:49–59.

Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PA, et al. Cancer patient preferences for communication of prognosis in the metastatic setting. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1721–30.

Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Saul J. Information needs of patients with cancer: Results from a large study in UK cancer centres. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:48–51.

Wessels H, de Graeff A, Wynia K, et al. Gender-related needs and preferences in cancer care indicate the need for an individualized approach to cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15:648–55.

Parker PA, Baile WF, de Moor C, Lenzi R, Kudelka AP, Cohen L. Breaking bad news about cancer: Patients' preferences for communication. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2049–56.

Yun YH, Lee CG, Kim S, et al. The attitudes of cancer patients and their families toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:307–14.

McArthur LZ, Baron RM. Towards an ecological theory of social perception. Psychol Rev. 1983;90:215–38.

Zajonc RB. On the primacy of affect. Am Psychol. 1984;39:117–23.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Contributors

We would like to thank Patriek Mistiaens and Jan Schoones for their help with creating the search string. We would like to thank Rinske van der Berg and Linda Schoonmade for their help with adjusting the search string for the different databases. We would like to thank the PPI for their valuable comments on an earlier version of the Manuscript.

Funders

This project was funded by the Spinoza Prize awarded to Prof. Jozien Bensing, PhD by the Dutch Research Counsel (NWO). The NWO was not involved in the research process.

Prior presentations

None

Conflict of Interest

L. M van Vliet has no conflicts of interest to declare.

E. van der Wall has no conflicts of interest to declare.

A. Albada has no conflicts of interest to declare.

P. Spreeuwenberg has no conflicts of interest to declare.

W. Verheul has no conflicts of interest to declare.

J. M Bensing has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited. Open Access was funded by the NWO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Vliet, L.M., van der Wall, E., Albada, A. et al. The Validity of Using Analogue Patients in Practitioner–Patient Communication Research: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 27, 1528–1543 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2111-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2111-8