Abstract

Background

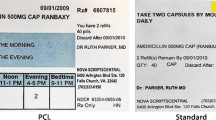

Patient misunderstanding of instructions on prescription drug labels is common and a likely cause of medication error and less effective treatment.

Objective

To test whether the use of more explicit language to describe dose and frequency of use for prescribed drugs could improve comprehension, especially among patients with limited literacy.

Design

Cross-sectional study using in-person, structured interviews.

Patients

Three hundred and fifty-nine adults waiting for an appointment in two hospital-based primary care clinics and one federally qualified health center in Shreveport, Louisiana; Chicago, Illinois; and New York, New York, respectively.

Measurement

Correct understanding of each of ten label instructions as determined by a blinded panel review of patients’ verbatim responses.

Results

Patient understanding of prescription label instructions ranged from 53% for the least understood to 89% for the most commonly understood label. Patients were significantly more likely to understand instructions with explicit times periods (i.e., morning) or precise times of day compared to instructions stating times per day (i.e., twice) or hourly intervals (89%, 77%, 61%, and 53%, respectively, p < 0.001). In multivariate analyses, dosage instructions with specific times or time periods were significantly more likely to be understood compared to instructions stating times per day (time periods — adjusted relative risk ratio (ARR) 0.42, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.34–0.52; specific times — ARR 0.60, 95% CI 0.49–0.74). Low and marginal literacy remained statistically significant independent predictors of misinterpreting instructions (low - ARR 2.70, 95% CI 1.81–4.03; marginal -ARR 1.66, 95% CI 1.18–2.32).

Conclusions

Use of precise wording on prescription drug label instructions can improve patient comprehension. However, patients with limited literacy were more likely to misinterpret instructions despite use of more explicit language.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Institute of Medicine. In: Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M, eds. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000.

Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J, Seger AC, Peterson J, Burdick E, et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1556–64.

Institute of Medicine. In: Aspden P, Wolcott J, Bootman L, Cronenwett LR, eds. Preventing Medication Errors. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2006.

Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, Tilson H, Neuberger M, Parker RM. Literacy and misunderstanding of prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:887–94.

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Prescription Drug Trends: A Chartbook Update. November 2001; http://www.kff.org. Accessed September 2008.

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [on-line]. Available at http://www.meps.ahrq.gov. Accessed September, 2008.

Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, Middlebrooks M, Kennan E, Baker DW, Bennett CL, Durazo-Arvizu R, Savory S, Parker RM. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:847–51.

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, Neuberger M, Parker RM. A critical review of FDA-approved Medication Guides. Pat Educ Counsel. 2006;62:316–22.

Gustafsson J, Kalvemark S, Nilsson G, et al. Patient information leaflets: patients’ comprehension of information about interactions and contraindications. Pharm World Sci. 2005;27:35–40.

Shrank WH, Avorn J, Rolón C, Shekelle P. The Effect of the Content and Format of Prescription Drug Labels on Readability, Understanding and Medication Use: A Systematic Review. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:783–801.

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Bass PF, Tilson H, Parker RM. Misunderstanding prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. Am J Health System Pharm. 2006;63:1048–55.

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, Rapp D, Connor U, Clayman M, Parker RM. To err is human: patient misinterpretations of prescription drug dosage instructions. Pat Educ Counsel. 2007;67:293–300.

Park DC, Jones TR. Medication adherence and aging. In: Fisk AD, Rogers WA, eds. Handbook of Human Factors and the Older Adult. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997:257–87.

Morrow DG, Leirer VO, Sheikh J. Adherence and medication instructions: review and recommendations. J Am Geriatric Soc. 1988;36:1147–60.

Park DC, Morrell RW, Frieske D, Kincaid D. Medication adherence behaviors in older adults: effects of external cognitive supports. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:252–6.

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–5.

Davis TC, Michielutte R, Askov EN, Williams MV, Weiss BD. Practical assessment of adult literacy in healthcare. Health Ed Beh. 1998;25:613–24.

Davis TC, Kennen EM, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV. Literacy testing in health care research. In: Schwartzberg JG, VanGeest JB, Wang CC, eds. Understanding health literacy: Implications for medicine and public health. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2004:157–79.

Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;1010537–41. Oct.

Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22.

Davis CS. Statistical Methods for the Analysis of Repeated Measurements. New York: Springer; 2002.

Davis TC, Fredrickson D, Arnold C, Murphy P, Herbst M, Bocchini J. A Polio Immunization Pamphlet with Increased Appeal and Simplified Language Does Not Improve Comprehension to an Acceptable Level. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:25–37.

Rice GE, Okun MA. Older readers’ processing of medical information that contradicts their beliefs. J Gerontol: Psych Sci. 1994;49:119–28.

Gien L, Anderson JA. Medication and the elderly: a review. J Geriatric Drug Ther. 1989;4:59–89.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000.

Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1855–62.

Morris LA, Tabak ER, Gondel K. Counseling patients about prescribed medications: 12-year trend. Med Care. 1997;35:996–1007.

Metlay JP, Cohen A, Polsky D, Kimmel SE, Koppel R, Hennessy S. Medication safety in older adults: home-based practice patterns. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:976–82.

Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Health Literacy: Report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. JAMA. 1999;281:552–7.

American Pharmaceutical Association. Committee Policy Report on Health Literacy 2001–2002.

Park DC, Gutchess AH, Meade ML, Stine-Morrow EA. Improving cognitive function in older adults: nontraditional approaches. J Gerontol. 2007;62B:45–52.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Mary Bocchini, Kat Davis, Sumati Jain, Jennifer Webb, Jessica Salazar and Silvia Skripkauskas. The study was supported in part by internal funding from the Health Literacy and Learning Program at Northwestern University.

Conflict Of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, T.C., Federman, A.D., Bass, P.F. et al. Improving Patient Understanding of Prescription Drug Label Instructions. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 57–62 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0833-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0833-4