Abstract

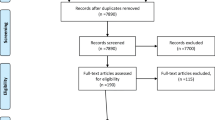

Objective The use of the Internet as a source of medicines information is increasing. However, the quality of online information is highly variable. Equipping Internet users to distinguish good quality information is the aim of a new five-item quality assessment tool (DARTS) that was developed by the Working Group on Information to Patients under the Pharmaceutical Forum established by the European Commission. The objective of this study was to investigate how people with depression assess the quality of online medicines information and to study their opinions about the DARTS tool in assisting in this process. Setting Focus group discussions with Internet users were conducted in metropolitan Helsinki, Finland. Method Six focus group discussions (67–109 min duration) were conducted with people with depression (n = 29). The DARTS tool was used as a stimulus after open discussion in relation to the evaluation of the quality of Internet-based medicines information. The focus groups were digitally audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were thematically content analysed by two researchers. Results Focus group participants were generally critical of the information they retrieved. However, few participants systematically applied quality assessment criteria when retrieving online information. No participants had knowledge or experience of any quality assessment tools. The DARTS tool was perceived as being concise and easy to use and understand. Many participants indicated it would allay some of their concerns related to information quality and act as a reminder. While several participants felt the tool should not be any more extensive, some of them believed it should include a more in-depth explanation to accompany each of the quality criteria. Conclusions The DARTS tool may act as a prompt for people with depression to assess the quality of online information they obtain. The five DARTS criteria may form the basis of a systematic approach to quality assessment and the tool may also act as a reminder of quality issues in general. Further studies are needed to assess the actual value of the DARTS tool as well as its value in relation to other quality assessment instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andreassen HK, Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Chronaki CE, Dumitru RC, Pudule I, Santana S, et al. European citizens’ use of E-health services: a study of seven countries. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:53. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-53.

Eysenbach G, Powell J, Kuss O, Sa E. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the World Wide Web. A systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:2691–700. doi:10.1001/jama.287.20.2691.

Eysenbach G. Consumer health informatics. BMJ. 2000;320:1713–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1713.

Bernstam E, Shelton D, Walji M, Meric-Bernstam F. Instruments to assess the quality of health information on the World Wide Web: what can our patients actually use? Int J Med Inform. 2005;74:13–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.10.001.

Wilson P. How to find good and avoid the bad or ugly: a short guide to tools for rating quality of health information on the internet. BMJ. 2002;324:598–602. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7337.598.

Morahan-Martin JA. How do internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: a cross-cultural review. Cyber Behav. 2004;7:497–510.

Haviland MG, Pincus HA, Dial TH. Type of illness and use of the internet for health information. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1198. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1198.

Powell J, Clarke A. Internet information-seeking in mental health: population survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:273–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017319.

Wagner TH, Baker LC, Bundorf K, Singer S. Use of the internet for health information by the chronically ill. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1:A13.

Bansil P, Keenan NL, Zlot AI, Gilliland JC. Health-related information on the Web: results from the Healthstyles Survey 2002–2003. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A36.

Berger M, Wagner TH, Baker LC. Internet use and stigmatized illness. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1821–7. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.025.

Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä M, Antila J, Eerikäinen S, Enäkoski M, Hannuksela O, Pietilä K, et al. Utilization of a community pharmacy operated national drug information call-center in Finland. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2008;4:144–52. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.05.001.

Bell S, McLachlan AJ, Aslani P, Whitehead P, Chen TF. Community pharmacy services to optimize the use of medications for mental illness: a systematic review. Aust NZ Health Policy. 2005;2:29. doi:10.1186/1743-8462-2-29.

Happell B, Manias E, Poper C. Wanting to be heard: mental consumers’ experiences of information about medication. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2004;13:242–8. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0979.2004.00340.x.

Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Quality of web based information on treatment of depression: cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2000;321(7275):1511–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1511.

Christensen H, Griffiths KM. The prevention of depression using the Internet. Med J Aust. 2002;177(Suppl):S122–5.

Graber MA, Weckmann M. Pharmaceutical company internet sites as sources of information about antidepressant medications. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:419–23. doi:10.2165/00023210-200216060-00005.

Lissman TL, Boehnlein JK. A critical review of Internet information about depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1046–50. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1046.

Pharmaceutical Forum—Introduction. DG Enterprise and Industry. http://www.ec.europa.eu/enterprise/phabiocom/comp_pf_en.htm

High level pharmaceutical forum public consultation on health-related information to patients—related documents. DG Enterprise and Industry. http://www.ec.europa.eu/enterprise/phabiocom/comp_pf_pat_reldoc.htm

Martin-Facklam M, Kostrzewa M, Schubert F, Gasse C, Haefeli WE. Quality markers of drug information on the Internet: an evaluation of sites about St. John’s Wort. Am J Med. 2002;113:740–5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01256-1.

Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet. JAMA. 1997;277:1244–5. doi:10.1001/jama.277.15.1244.

Eysenbach G. Infodemiology. The epidemiology of (Mis)information. Am J Med. 2002;113:763–5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01473-0.

Kitzinger J. Qualitative research: introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311:299–302.

Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä M, Saari JK, Närhi U, Karjalainen A, Pylkkänen K, Airaksinen MS, et al. How and why people with depression access and utilize online drug information: a qualitative study. J Affect Disord. In press.

National Agency for Medicines. http://www.nam.fi

Peterson G, Aslani P, Williams KA. How do consumers search for and appraise information on medicines on the Internet? A qualitative study using focus groups. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5:e33. doi:10.2196/jmir.5.4.e33.

Mieli Maasta ry— Depression alliance. http://www.mielimaasta.fi/english.html.

Finnish Student Health Service. http://www.fshs.fi/netcomm/default.asp?strLAN=EN.

Nyyti ry—opiskelijoiden tukikeskus. (In Finnish) http://www.nyyti.fi/.

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm

Närhi U. Sources of medicine information and their reliability evaluated by medicine users. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:688–94.

Discern. http://www.discern.org.uk/index.php.

Health on the Net Foundation. http://www.hon.ch/index.html.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. How to Evaluate Health Information on the Internet. http://www.fda.gov/oc/opacom/evalhealthinfo.html.

Plus Guide to Healthy Web Surfing. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/healthywebsurfing.html.

European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Guidelines for Internet Web sites available to health professionals, patients and the public in the EU. http://www.efpia.org/Objects/2/Files/Internetguidelines.pdf.

Winker MA, Flanagin A, Chi-Lum B, White J, Andrews K, Kennett RL, et al. Guidelines for medical and health information sites on the Internet. Principles governing AMA Web sites. JAMA. 2000;283:1600–6. doi:10.1001/jama.283.12.1600.

eEurope. Quality Criteria for Health related Websites. 2002. http://www.ec.europa.eu/information_society/eeurope/ehealth/doc/communication_acte_en_fin.pdf.

Analysis of 9th HON Survey of Health and Medical Internet Users Winter 2004–2005. Health on the Net Foundation. http://www.hon.ch/Survey/Survey2005/res.html.

Risk A, Dzenowagis J. Review of internet health information quality initiatives. J Med Internet Res. 2001;3:E28. doi:10.2196/jmir.3.4.e28.

Eysenbach G, Thomson M. The FA4CT algorithm: a new model and tool for consumers to assess and filter health information on the Internet. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129:142–6.

Childs S. Developing health website quality assessment guidelines for the voluntary sector: outcomes from the Judge Project. Health Info Libr J 2004, 21(Suppl 2):14–26

Sillence E, Briggs P, Harris PR, Fishwick L. How do patients evaluate and make use of online health information? Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1853–62. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.012.

Delamothe T. Quality of websites: kitemarking the west wind. BMJ. 2000;321:843–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7265.843.

Eysenbach G. The Semantic Web and healthcare consumers: a new challenge and opportunity on the horizon? Int J Healthc Technol Manage. 2003;3/4(5):194–212. doi:10.1504/IJHTM.2003.004165.

Jadad A, Gagliardi A. Rating health information on the Internet. Navigating to knowledge or to Babel? JAMA. 1998;279:611–4. doi:10.1001/jama.279.8.611.

Ademiluyi G, Rees C, Sheard C. Evaluating the reliability and validity of three tools to assess the quality of health information on the Internet. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:151–5.

Crawford MJ, Rutter D. Are the views of members of mental health user groups representative of those ‘ordinary’ patients? A cross-sectional survey of services users and providers. J Ment Health. 2004;13:561–8. doi:10.1080/09638230400017111.

Hill SA, Laugharne R. Decision making and information seeking preferences among psychiatric patients. J Ment Health. 2006;15:75–84. doi:10.1080/09638230500512250.

Pirkola SP, Isometsä E, Suvisaari J, Aro S, Joukamaa MJ, Poikolainen K, et al. DSM-IV mood-, anxiety- and alcohol use disorders and their comorbidity in the Finnish general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:1–10. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0848-7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Finnish Students Health Service, Mieli Maasta Ry Depression Alliance and Nyyti for their enthusiastic participation in this initiative. The authors are particularly grateful for the support and assistance provided by Dr Kari Pylkkänen and Ms Hilkka Kärkkäinen.

Funding

The study did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of interests

During the study, UN and AK worked for the National Agency for Medicines, Finland. UN was a member of the European Commission Pharmaceutical Forum Working Group on Information to Patients. At the moment, she works for the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1. Focus group guide

Appendix 1. Focus group guide

-

1.

Experiences in receiving information on antidepressants (in general)

-

2.

Antidepressant-related information needs

-

3.

Experiences in using different sources of medicines information

-

4.

The internet as a source of medicines information

-

5.

The methods and process of searching for Internet-based medicines information

-

6.

The evaluation of the quality of Internet-based medicines information

-

7.

Perceived impact of Internet-based medicines information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Närhi, U., Pohjanoksa-Mäntylä, M., Karjalainen, A. et al. The DARTS tool for assessing online medicines information. Pharm World Sci 30, 898–906 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-008-9249-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-008-9249-9