Abstract

Background and objective:

Pulmonary function and height may be regarded as adult indices of exposures accumulated across the entire life course and in early life, respectively. As such, we hypothesised that pulmonary function would be more strongly related to mortality than height. Studies of the association of height and lung function with mortality – which are currently modest in number – will clarify the relative utility of these risk indices and the mechanisms underlying observed patterns of disease risk.

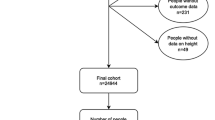

Design, setting, and participants:

Data were drawn from the Whitehall study, a prospective cohort study of 18,403 middle-aged non-industrial London-based male government employees conducted in the late 1960s. Data were collected on stature, spirometry measures (including forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1]) and a range of covariates. These analyses are based on the 3083 non-smoking men with complete data.

Main outcome measures:

Mortality ascribed to all-causes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and site-specific cancers.

Results:

Both height and FEV1 were associated with a range of physiological, behavioural and socio-economic risk factors. Relations with these risk factors were seen more frequently for FEV1 and, where they occurred, were of somewhat higher magnitude. During a maximum of 35 years follow-up, half the non-smokers had died (n = 1545). FEV1 (HRper one SD increase; 0.89; 0.84, 0.95) was somewhat more strongly related to total mortality than height (0.96; 0.91, 1.01) in a fully adjusted model, but this difference did not attain statistical significance at conventional levels (p-value for difference = 0.15). Of the eight independent disease-specific outcomes examined, the only convincing evidence of a differential effect was for deaths from respiratory causes which was unsurprisingly more strongly related to FEV1 than height (p-value for difference = 0.03).

Conclusions:

In the present study, height and FEV1 were essentially similarly related to both risk factors and mortality outcomes, thus not providing support for our hypothesis. Both factors would appear to have some utility as markers of early life exposures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kuh D, Ben Shlomo Y (2004) A lifecourse approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford

Lynch J, Davey Smith G (2005) A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health 26: 1–35

Gunnell D, Okasha M, Davey Smith G, Oliver SE, Sandhu J, Holly JM (2001) Height, leg length, and cancer risk: a systematic review. Epidemiol Rev 23: 313–342

Langenberg C, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, Marmot MG (2005) Adult socioeconomic position and the association between height and coronary heart disease mortality: findings from 33 years of follow-up in the whitehall study. Am J Public Health 95: 628–632

Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Langenberg C, Marmot MG, Davey SG (2006) Adult height in relation to mortality from 14 cancer sites in men in London (UK): evidence from the original Whitehall study. Ann Oncol 17: 157–166

Sin DD, Wu L, Man SF (2005) The relationship between reduced lung function and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based study and a systematic review of the literature. Chest 127: 1952–1959

Gunnell D. Can adult anthropometry be used as a ‘biomarker’ for prenatal and childhood exposures? Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 390–394

Strachan DP. Respiratory and alleregic diseases. In: Kuh D (ed), A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997: 101–120

Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Fall C, Osmond C, Winter PD, Shaheen SO (1991) Relation of birth weight and childhood respiratory infection to adult lung function and death from chronic obstructive airways disease. BMJ 303: 671–675

Upton MN, Smith GD, McConnachie A, Hart CL, Watt GC (2004) Maternal and personal cigarette smoking synergize to increase airflow limitation in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169: 479–487

Strachan DP (1992) Ventilatory function, height, and mortality among lifelong non-smokers. J Epidemiol Community Health 46:66–70

Gunnell D, Whitley E, Upton MN, McConnachie A, Smith GD, Watt GC (2003) Associations of height, leg length, and lung function with cardiovascular risk factors in the midspan family study. J Epidemiol Community Health 57: 141–146

Reid DD, Hamilton PJS, McCartney P, Rose G, Jarrett RJ, Keen H, etal (1974) Cardiorespiratory disease and diabetes among middle-aged male civil servants. Lancet i: 469–473

Vineis P, Alavanja M, Buffler P, Fontham E, Franceschi S, Gao YT, etal (2004) Tobacco and cancer: recent epidemiological evidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 99–106

Davey Smith G, Leon D, Shipley MJ, Rose G (1991) Socioeconomic differentials in cancer among men. Int J Epidemiol 20: 339–345

Anon. Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death (eighth revision). Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1967

Anon. Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death (ninth revision). Geneva: WHO, 1977

Anon. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th revision). Geneva: WHO, 1992

Cox DR. Regression Models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc [Ser B] 1972; 34: 187–220

SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT(R) User’s Guide, Version 6, Volumes 1 & 2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 1989

Davey Smith G, Hart C, Upton M (2000) Height and risk of death among men and women: aetiological implications of associations with cardiorespiratory disease and cancer mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health 54:97–103

Walker M, Shaper AG, Phillips AN, Cook DG (1989) Short stature, lung function and risk of a heart attack. Int J Epidemiol 18:602–606

Rich-Edwards JW, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rosner B, etal (1995) Height and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women. Am J Epidemiol 142:909–917

Song YM, Davey Smith G, Sung J (2003) Adult height and cause-specific mortality: a large prospective study of South Korean men. Am J Epidemiol 158:479–485

Lee IM, Paffenbarger RS, Hsieh CC (1992) Time trends in physical activity among college alumni 1962–1988. Am J Epidemiol 135:915–925

Strachan D (1991) Ventilatory function as a predictor of stroke. BMJ 302:84–87

Mannino DM, Ford ES, Redd SC (2003) Obstructive and restrictive lung disease and functional limitation: data from the third national health and nutrition examination. J Intern Med 254:540–547

Acknowledgements

Contributions: David Gunnell and David Batty generated the idea for this manuscript. Martin Shipley conducted all data analyses. David Batty wrote the first draft of the manuscript on which co-authors commented.

Funding: With thank the civil servants who gave of their time to participate in the baseline survey in the 1960s which was funded by the then Department of Health and Social Security and the Tobacco Research Council. Martin Shipley is currently supported by the British Heart Foundation; Michael Marmot by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC); Claudia Langenberg by a UK MRC Research Training Fellowship; and David Batty by a Wellcome Advanced Training Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Batty, G.D., Gunnell, D., Langenberg, C. et al. Adult height and lung function as markers of life course exposures: Associations with risk factors and cause-specific mortality. Eur J Epidemiol 21, 795–801 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-006-9057-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-006-9057-2