Abstract

Limited data exist regarding treatment patterns and outcomes in elderly patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC). registHER is an observational study of patients (N = 1,001) with HER2-positive MBC diagnosed within 6 months of enrollment and followed until death, disenrollment, or June 2009 (median follow-up 27 months). Outcomes were analyzed by age at MBC diagnosis: younger (<65 years), older (65–74 years), elderly (≥75 years). For progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) analyses of first-line trastuzumab versus nontrastuzumab, older and elderly patients were combined. Cox regression analyses were adjusted for baseline characteristics and treatments. Estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor status was similar across age groups. Underlying cardiovascular disease was most common in elderly patients. In patients receiving trastuzumab-based first-line treatment, elderly patients were less likely to receive chemotherapy. In trastuzumab-treated patients, incidence of left ventricular dysfunction (LVD) and congestive heart failure (CHF) (grades ≥ 3) were highest in elderly patients (LVD: elderly 4.8 %, younger 2.8 %, older 1.5 %; CHF: elderly 3.2 %, younger 1.9 %, older 1.5 %). Unadjusted median PFS (months) was significantly higher in patients treated with first-line trastuzumab than those who were not (<65 years: 11.0 vs. 3.4, respectively; ≥65 years: 11.7 vs. 4.8, respectively). In patients <65 years, unadjusted median OS (months) was significantly higher in trastuzumab-treated patients; in patients ≥65 years, median OS was similar (<65 years: 40.4 vs. 25.9; ≥65 years: 31.2 vs. 28.5). In multivariate analyses, first-line trastuzumab use was associated with significant improvement in PFS across age. For OS, significant improvement was observed for patients <65 years and nonsignificant improvement for patients ≥65 years. Elderly patients with HER2-positive MBC had higher rates of underlying cardiovascular disease than their younger counterparts and received less aggressive treatment, including less first-line trastuzumab. These real-world data suggest improved PFS across all age groups and similar trends for OS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the US, breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths in women aged ≥65 years [1–3], and the average age at diagnosis is approximately 63 years [3]. In the 2000–2008 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, nearly 50 % of breast cancer cases occurred in women aged ≥65 years, and 47 % occurred in women aged ≥70 years [4]. Despite the high incidence and mortality of breast cancer in older women, knowledge about aging and breast cancer and about optimal treatment for older cancer patients is inadequate, mostly due to the underrepresentation of these patients in prospective clinical trials [5]. Cancer patients age 70 or greater comprised only 20 % of subjects enrolled in US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) registration trials from 1995 to 1999, though they made up fully 46 % of the US cancer population [6].

Elderly breast cancer patients are often underrepresented in clinical trials because of higher rates of underlying comorbidities, concerns about toxicity of therapies, including cardiotoxicity, risks of mortality, and other reasons [7–9]. Elderly patients are also underrepresented in clinical trials due to “physician bias,” based on the concern that a patient will not tolerate or benefit from treatment, and “patient and family member bias,” based on the belief that the treatment may not be worthwhile or too toxic [4]. Because of the scarcity of randomized trials which include elderly patients, there is little evidenced-based data on treatment-related outcomes in this patient population [10], yet available studies indicate that older women are less likely to receive standard therapy for their breast cancer [7, 10–13]. In a review of 407 breast cancer patients aged ≥80 years, Bouchardy et al. [14] reported that half were undertreated, with significantly decreased survival in this cohort as a consequence.

HER2-positive breast cancer, which comprises 20–25 % of breast cancer, is associated with poor prognosis and is a significant adverse predictor of both overall survival (OS) and time to relapse [15–17]. We examined a large cohort of elderly patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC) to date in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and safety and efficacy outcomes in the registHER observational study. This population registry provides a unique opportunity to gain important insights and valuable benchmarks to guide clinical management of these patients.

Methods

Study design and patients

registHER is a prospective, multicenter, observational US-based cohort study of 1,023 patients (n = 1,013 women and n = 10 men) recruited from community and academic settings between December 2003 and February 2006. The objectives of the registHER study were to describe the natural history of disease and treatment patterns for patients with HER2-positive MBC, and to explore associations between demographic and clinical factors, specific therapies, and patient outcomes.

Details regarding the registHER study design and recruitment are described elsewhere [18]. In brief, patients with a history of either recurrent metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer or those presenting with an initial diagnosis of metastatic (stage IV) breast cancer were eligible within 6 months of this diagnosis, provided that all required cancer-specific historical data points were available in the medical record. Patients received care according to their physicians’ standard practice without any study-specified therapy or evaluations. Prior or planned treatment with trastuzumab, or any specific HER2-targeted therapy, was not a requirement for study participation. All patients signed an informed consent and authorization to disclose their health information. There were no exclusion criteria for participation in the study; however, patients who did not consent and provide authorization of health information disclosure were excluded.

Data collection

Data collected for enrolled patients included demographics, height and weight, cardiac history and other significant comorbidities, date of initial breast cancer diagnosis and stage, histology, hormone receptor (HR) and HER2 status, prior adjuvant or radiotherapy, and date of MBC diagnosis with sites of metastatic disease at diagnosis.

After enrollment, follow-up was done every 3 months thereafter, at which time treatment history, sites of progressive disease, tumor response, survival, cardiac safety (grades 3/4/5), and adverse events possibly related to the administration of trastuzumab were collected. Cardiac safety events were defined based on the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, v3.0, and selected based on physician subjective opinion [19].

Treatments for MBC were administered according to standard-of-care by the treating oncologist. Formal, prespecified, and scheduled assessments for tumor response were not required, and tumor response or progression was reported by physicians according to their standard judgment and practice.

Statistical methods

Enrollment of 83 patients whose MBC diagnosis was more than 6 months (up to 9 months) prior to enrollment was permitted and these patients are included in all analyses. A total of 22 patients did not receive any treatment during the study and were excluded. Trastuzumab-based regimens were defined as patients receiving ≥21 days of trastuzumab in the first line. For this analysis, patients were stratified into three groups based on age at MBC diagnosis: younger (<65 years), older (65–74 years), elderly (≥75 years). Demographic and clinical characteristics were generated across each age group (younger, older, and elderly). For progression-free survival (PFS) and OS analyses of first-line trastuzumab versus nontrastuzumab, older and elderly patients were combined due to the small number of events in the elderly (<65 vs. ≥65). OS was based on overall cancer-related deaths, as breast cancer-specific mortality was not collected in registHER.

PFS and OS were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. A hierarchical modeling approach was used in the multivariate analysis to assess the effects of age, first-line trastuzumab use (yes vs. no), and their interaction on time to event endpoints. The initial Cox proportional model included only age and first-line trastuzumab use. The following patient baseline characteristics were subsequently adjusted for in the multivariate models: race/ethnicity, European Cooperative Group (ECOG) performance status, serum albumin level, estrogen/progesterone receptor (ER/PR) status, site of metastatic disease, number of metastatic sites, stage of disease at initial diagnosis, history of underlying cardiovascular disease (CVD), and history of other underlying noncardiac comorbidities. The final multivariate models further adjusted for patient first-line treatment variables, such as receiving first-line chemotherapy and first-line hormonal therapy. All models were fitted with and without age and first-line trastuzumab use interaction terms.

Results

Patient baseline and clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the 1,001 patients who were followed until death, disenrollment, or the June 2009 data lock (median follow-up was 27 months). The median age of younger (<65 years) patients was 50 years, for older (65–74 years) patients it was 69 years, and for elderly (≥75 years) patients it was 79 years. The great majority of patients in each age group were female (99–100 %). Elderly (≥75 years) patients were more likely to be white and less likely to be obese (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2) compared with younger and older patients. Most patients had ECOG status of 0–1 at diagnosis.

Distribution of site of metastatic disease at diagnosis of MBC showed central nervous system (CNS) and visceral metastases were less common in elderly patients compared with the other age groups, whereas metastases to bone or bone plus breast and node/local sites at diagnosis were more common in elderly patients. Also, elderly patients were most likely to have had clinical stage I–III disease at the time of initial diagnosis with a disease-free interval of >12 months (72.3 %), compared with younger (57.7 %) and older patients (61.1 %). Elderly patients were also least likely to have had initial diagnosis of early stage disease with disease-free interval of ≤12 months (6.2 %) compared with younger (13.6 %) and older (16.0 %) patients. ER/PR status was similar across age groups, and approximately half of patients in all groups were ER/PR-positive.

Elderly patients were also most likely to have a history of diabetes (16.9 %) compared with younger (5.9 %) and older (14.6 %) patients. In addition, at baseline, elderly patients had a higher rate of underlying CVD, with 46.2 % reporting some type of CVD at baseline compared with 29.2 % in older and 12.6 % in younger patients. Elderly patients were most likely to report arrhythmia, hypertension with complications, congestive heart failure (CHF), myocardial infarction, and “other” underlying cardiac diseases.

Treatment patterns prior to first disease progression

First-line treatment patterns are based on treatment received after diagnosis of metastatic disease and prior to first disease progression and may have been given sequentially or concurrently. Elderly patients were least likely to receive trastuzumab-based first-line treatment (77 %, 50/65) compared with older patients (81 %, 117/144) and younger patients (85 %, 674/792), although these differences were modest. Among patients receiving trastuzumab-based first-line treatment, elderly patients were least likely to receive chemotherapy plus trastuzumab and most likely to receive trastuzumab alone or combined with hormonal therapy compared with younger and older patients (Table 2). Among patients receiving nontrastuzumab-based first-line treatment, elderly patients were least likely to receive chemotherapy only and most likely to receive hormonal therapy only or hormonal therapy combined with chemotherapy compared with the other age groups.

Cardiac safety outcomes

Table 3 shows the incidence of cardiac adverse events (grades ≥ 3) for all patients treated with trastuzumab. In the 63 elderly patients included in the analysis, the incidence of any cardiac adverse event was 25.4 %, compared with 6.8 % in younger and 6.7 % in older patients. The incidence of left ventricular dysfunction (LVD) was highest in elderly patients (4.8 %) compared with younger (2.8 %) and older patients (1.5 %). The incidence of CHF was also highest in elderly patients (3.2 %) compared with younger (1.9 %) and older patients (1.5 %). When stratified by underlying disease history, elderly patients with a history of hypertension with complications or any CVD were more likely to have cardiac safety events and compromise of left ventricle function compared with younger or older patients. Specifically, of the elderly patients reporting hypertension with complications (n = 8), 25.0 % (n = 2) had any cardiac safety event and 25.0 % (n = 2) had LVD compared with younger patients (0 % for either cardiac or LVD) and older patients [11.1 % (n = 2) for cardiac, 0 % for LVD]. Similarly, of the elderly patients reporting underlying cardiovascular disease (n = 27), 33.3 % (n = 9) had a cardiac safety event and 11.1 % (n = 3) had an LVD event compared with younger patients [5.3 % (n = 5) for cardiac, 0 % for LVD] and older patients [7.7 % (n = 3) for cardiac, 0 % for LVD]. Due to the small number of safety events, these associations were not statistically significant.

Rates of cancer-related deaths were similar across age groups: (81.4 %, 35/43) in elderly patients, (82.4 %, 70/85) in older patients, and (89.5 %, 367/410) in younger patients.

Survival outcomes based on trastuzumab treatment

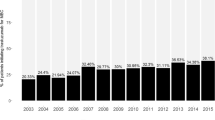

For PFS and OS analyses of first-line trastuzumab versus nontrastuzumab, older and elderly patients were combined due to the small number of events in the elderly. For patients aged <65 years, unadjusted median PFS was significantly greater for patients treated with first-line trastuzumab versus patients not treated with first-line trastuzumab (11.0 vs. 3.4 months); in patients ≥65 years, PFS was also significantly higher in trastuzumab-treated patients (11.7 vs. 4.6 months) (Fig. 1, panels a, b). In patients aged <65 years, unadjusted median OS was significantly higher in trastuzumab-treated patients (40.4 months trastuzumab vs. 25.9 months nontrastuzumab); in patients ≥65 years, median OS was similar in both the treatment groups (31.2 months trastuzumab vs. 28.5 months nontrastuzumab) (Fig. 1, panels c, d).

In multivariate analyses (Table 4), trastuzumab used in first-line therapy was associated with significant improvement in PFS across age groups. For OS, significant improvement was observed for patients <65 years; a nonsignificant improvement for patients ≥65 years was observed. Age and first-line trastuzumab use interaction terms were not statistically significant (data not shown).

Clinical outcomes

Among all treated patients with disease progression, rates of CNS metastasis were lowest in the elderly (9.3 %) compared with younger (22.3 %) and older (16.8 %) patients (Fig. 2). Rates of first disease progression to visceral, node/locoregional, and other sites were the same or increased in elderly patients compared with other age groups, while rates were lower for bone only or bone and breast for the elderly patients compared with younger.

Discussion

There continues to be a paucity of data characterizing elderly breast cancer patients. With the increasingly older world population, oncologists are faced with an imposing challenge due to the growing cancer burden and the specific health care needs of older cancer patients [10, 20]. With the largest cohort of HER2-positive elderly breast cancer patients to date, the registHER study allows the unique and important opportunity to examine the natural history of disease and treatment patterns in these patients. Elderly patients had higher rates of underlying CVD and were less likely to be treated with cytotoxic therapies compared with their younger counterparts. While there was an increased incidence of CVD events in the elderly during follow-up, there was evidence of an association with comorbidities, including hypertension with complications and any CVD. Among treated patients with disease progression, the rate of CNS metastasis decreased with increasing age. This observation of a decreased incidence of CNS metastases in patients with HER2-positive MBC with increasing age has not been appreciated previously. Regardless of age, among patients receiving first-line treatment with trastuzumab, PFS was higher compared with those not treated with trastuzumab. OS was higher for patients <65 years and similar for patients ≥65 years of age.

Elderly patients (≥75 years) with HER2-positive MBC in registHER had higher rates of underlying CVD than their younger counterparts. The increased incidence of CVD events in elderly patients during 27 months of follow-up was clinically modest (the incidences of LVD and CHF were each below 5 %). However, a subanalysis noting a possible association with underlying comorbidities suggested a possible subset of elderly patients (those hypertension with complications and any underlying CVD) at an increased risk of CVD events, although these results are based on small numbers. Our findings compare favorably with a recent population-based study assessing the risk of cardiotoxicities in association with trastuzumab with/without anthracyclines in 47,806 women aged ≥65 years with breast cancer diagnosed between 1998 and 2005 [21]. The cumulative incidence of CHF at Year 1 was 5.5 % for patients receiving anthracycline and trastuzumab, and 7.8 % for patients receiving trastuzumab without anthracycline. Consistent with our findings, risk factors for trastuzumab cardiotoxicity in another study included age >50, hypertension, and baseline cardiac dysfunction [22]. In a recent retrospective study of 45 patients, trastuzumab-treated elderly breast cancer patients (aged ≥ 70 years) with a history of cardiac disease and/or diabetes had an increased incidence of cardiotoxicity [23]: the overall incidence of cardiac events was 26.7 % (n = 12 patients), in which 8 patients (17.8 %) developed asymptomatic left ventricular ejection fraction decline and 4 patients (8.9 %) developed symptomatic CHF. This incidence is higher than that reported in the recently published Cochrane meta-analysis of trastuzumab clinical trials [24], although this report encompassed patients of all the age groups.

It is important to note that our follow-up period of 27 months likely captured all toxicity events in the registHER cohort. In a real-world, multicenter study of 499 consecutive patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer, trastuzumab cardiotoxicity most often occurred in the first 3 months of therapy (41 % of cases), with the greatest prevalence in older patients with higher creatinine levels and in patients pretreated with doxorubicin and radiotherapy [25]. These results highlight the importance of obtaining a full medical history from patients before initiating anti-HER2 therapies to identify potential risk factors for cardiac dysfunction.

In our study, regardless of age, PFS was significantly higher in patients receiving first-line trastuzumab therapy compared with patients not treated with trastuzumab; for OS, significant improvement was observed for patients <65 years. A nonsignificant improvement was observed for trastuzumab-treated patients ≥65 years, which may be due to the small number of events in this age group. It is also possible that competing mortality from other causes in the ≥65-year-old age group diluted the mortality benefit from trastuzumab. These findings support those from a recent study by Griffiths et al. [26] who used the national SEER database to describe a large cohort (N = 610) of older women (mean age 74 years) with HER2-positive MBC treated with first-line or delayed trastuzumab treatment. Their findings showed that OS in older women with HER2-positive MBC treated with trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy were similar to outcomes reported for younger patients.

The observation of decreasing CNS metastasis with increasing age may be due to underlying pathophysiology or treatment effects (or both). Other evidence suggests that older patients are less likely to develop CNS metastases. In another study of the registHER population which included 1,012 patients who had confirmed HER2-positive tumors, Brufsky et al. [18] found that those with CNS metastases were younger (≤65 years) and also more likely to have HR-negative disease [18]. Similarly, in a separate study in 2,685 primary breast cancer patients, those at increased risk for CNS metastasis were younger and ER− or PR−; importantly, adjuvant systemic therapies in this study were not associated with an increase in CNS metastasis risk [27]. Indeed, as trastuzumab and most chemotherapeutic agents do not readily cross an intact blood brain barrier [18, 28], and as elderly patients in registHER were less likely to receive cytotoxics, the observation of decreased CNS metastasis in the elderly is potentially due to a combination of both disease pathophysiology and treatment effects. These findings warrant further research.

An inherent limitation of this study is possible “confounding by indication,” due to the nonrandomized, observational nature of the registHER study. In observational studies, bias from confounding by indication—also referred to as “treatment selection bias”—may result because selection of treatments is not random and is determined by patient and physician characteristics; the observed effect can, therefore, be influenced by factors other than the treatment. There is also the potential for residual confounding by certain clinical factors that may not have been collected or sufficiently captured. Because patients may have had a diagnosis of MBC up to 9 months prior to enrollment and patients with longer survival may be more likely to enroll, OS estimates from time of MBC diagnosis in registHER may be slightly higher than expected in a general MBC patient population. Finally, limited information was collected for cause of death in registHER (options included only “cancer” and “other”) and cause of death was missing for >5 % of deaths, which precluded the calculation of breast cancer-specific mortality rates in this study. Our findings should also be interpreted with caution, due to the small number of events in elderly patients in our study.

Conclusions

Consistent with data from prospective randomized phase III trials [29, 30], these real-world data from the registHER study suggest improved PFS across all age groups, with OS benefits for the younger and older groups, and a possible trend for OS in the elderly. While elderly patients had higher rates of underlying CVD, they maintained a tolerable cardiac safety profile for trastuzumab compared with younger patients. Nonetheless, it is important that cardiac risk factors be taken into account when making treatment decisions, in addition to ongoing monitoring for the emergence of such events. We report a substantial decrease in the incidence of CNS metastases with increasing age in elderly patients with HER2-positive MBC. The data from this analysis of HER2-positive elderly patients will provide oncologists with a better understanding of this patient population and may help guide treatment in both the clinic and the future clinical trials. Enhancing our knowledge in treating the MBC patient is particularly crucial in the undertreated elderly patient, who has a more limited life expectancy.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- FDA:

-

Federal Drug Administration

- HR:

-

Hormone receptor

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- LVD:

-

Left ventricular dysfunction

- MBC:

-

Metastatic breast cancer

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- OS:

-

Overall survival

References

Balducci L, Phillips DM (1998) Breast cancer in older women. Am Fam Physician 58:1163–1172

Downey L, Livingston R, Stopeck A (2007) Diagnosing and treating breast cancer in elderly women: a call for improved understanding. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:1636–1644

Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Theodoulou M, Mauer Am, Kornblith AB, Partridge AH, Dressler LG, Cohen HJ, Becker HP, Kartcheske PA, Wheeler JD, Perez EA, Wolff AC, Gralow JR, Burstein HJ, Mahmood AA, Magrinat G, Parker BA, Hart RD, Grenier D, Norton L, Hudis CA, Winder EP, CALGB Investigators (2009) Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 360:2055–2065

Crivellari D, Aapro M, Leonard R, von Minckwitz G, Brain E, Goldhirsch A, Veronesi A, Muss H (2007) Breast cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol 25:1882–1890

Pallis AG, Fortpied C, Wedding U, Van Nes MC, Penninckx B, Ring A, Lacombe D, Monfardini S, Scalliet P, Wildiers H (2012) EORTC elderly task force position paper: approach to the older cancer patient. Eur J Cancer 46:1502–1513

Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R (2004) Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol 22:4626–4631

Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA Jr, Albain KS (1999) Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 341:2061–2067

Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL (2005) Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 23:3112–3124

Pinder MC, Duan Z, Goodwin JS, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH (2007) Congestive heart failure in older women treated with adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:3808–3815

Biganzoli L, Wildiers H, Oakman C, Marotti L, Loibl S, Kunkler I, Reed M, Ciatto S, Voogd AC, Brain E, Cutuli B, Terret C, Gosney M, Aapro M, Audisio R (2012) Management of elderly patients with breast cancer: updated recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) and European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA). Lancet Oncol 13:e148–e160

Du X, Goodwin JS (2001) Patterns of use of chemotherapy for breast cancer in older women: findings from Medicare claims data. J Clin Oncol 19:1455–1461

Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, Havlik RJ, Edwards BK, Yates JW (2001) Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA 285:885–892

Townsley C, Pond GR, Peloza B, Kok J, Naidoo K, Dale D, Herbert C, Holowaty E, Straus S, Siu LL (2005) Analysis of treatment practices for elderly cancer patients in Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol 23:3802–3810

Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, Laissue P, Neyroud-Caspar I, Schäfer P, Kurtz J, Sappino AP, Vlastos G (2003) Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol 21:3580–3587

Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL (1987) Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 235:177–182

Kallioniemi OP, Holli K, Visakorpi T, Koivula T, Helin HH, Isola JJ (1991) Association of c-erbB-2 protein over-expression with high rate of cell proliferation, increased risk of visceral metastasis and poor long-term survival in breast cancer. Int J Cancer 49:650–655

Estevez L, Seidman A (2003) HER2-positive breast cancer: incidence, prognosis, and treatment options. Am J Cancer 2:169–179

Brufsky AM, Mayer M, Rugo HS, Kaufman PA, Tan-Chiu E, Tripathy D, Tudor IC, Wang LI, Brammer MG, Shing M, Yood MU, Yardley DA (2011) Central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: incidence, treatment, and survival in patients from registHER. Clin Cancer Res 14:4834–4843

National Cancer Institute (2006) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2012

Monfardini S, Yancik R (1993) Cancer in the elderly: meeting the challenge of an aging population. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:532–538

Du XL, Xia R, Burau K, Liu C-C (2005) Cardiac risk associated with the receipt of anthracycline and trastuzumab in a large nationwide cohort of older women with breast cancer, 1998–2005. Med Oncol 28:S80–S90

Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, Sledge GW, Kaufman PA, Hudis CA, Martino S, Gralow JR, Dakhil SR, Ingle JN, Winer EP, Gelmon KA, Gersh BJ, Jaffe AS, Rodeheffer RJ (2008) Cardiac safety analysis of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzumab in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol 26:1231–1238

Serrano C, Cortés J, De Mattos-Arruda L, Bellet M, Gómez P, Saura C, Pérez J, Vidal M, Muñoz-Couselo E, Carreras MJ, Sánchez-Ollé G, Tabernero J, Baselga J, Di Cosimo S (2012) Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity in the elderly: a role for cardiovascular risk factors. Ann Oncol 23:897–902

Moja L, Tagliabue L, Balduzzi S, Parmelli E, Pistotti V, Guarneri V, D’Amico R (2012) Trastuzumab containing regimens for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 4:CD006243

Tarantini L, Cioffi G, Gori S, Tuccia F, Boccardi L, Bovelli D, Lestuzzi C, Maurea N, Oliva S, Russo G, Faggiano P, Italian Cardio-Oncologic Network (2012) Trastuzumab adjuvant chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity in real-world women with breast cancer. J Card Fail 18:113–119

Griffiths RI, Lalla D, Herbert RJ, Doan JF, Brammer MG, Danese MD (2011) Infused therapy and survival in older patients diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer who received trastuzumab. Cancer Invest 29:573–584

Tham YL, Sexton K, Kramer R, Hilsenbeck S, Elledge R (2006) Primary breast cancer phenotypes associated with propensity for central nervous system metastases. Cancer 107:696–704

Pienkowski T, Zielinski CC (2010) Trastuzumab treatment in patients with breast cancer and metastatic CNS disease. Ann Oncol 21:917–924

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, Baselga J, Norton L (2001) Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 344:783–792

Marty M, Cognetti F, Maraninchi D, Snyder R, Mauriac L, Tubiana-Hulin M, Chan S, Grimes D, Anton A, Lluch A, Kennedy J, O’Byrne K, Conte P, Green M, Ward C, Mayne K, Extra JM (2005) Randomized phase II trial of the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab combined with docetaxel in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer administered as first-line treatment: the M77001 study group. J Clin Oncol 23:4265–4274

Acknowledgments

The registHER study is funded by Genentech, Inc. The authors thank Lee Bennett and Yun Wu of RTI-Health Solutions for conducting data analyses, and Melissa Brammer, MD, MPH, of Genentech, Inc. for her input on the manuscript. Tmirah Haselkorn, PhD (EpiMetrix, Inc.), a professional medical writer funded by Genentech, Inc., assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

PAK has received research grant support from Genentech, Inc., and has performed consulting services for Genentech, Inc. HSR has received research support from Genentech to UCSF. DT has received honoraria for consulting from Genentech, Inc. for participation in a Steering Committee for a registry. AMB and MY serve as paid consultants/advisory board members to Genentech, Inc. DAY and MM serve as unpaid consultants/advisory board members to Genentech, Inc. CQ, LIW, and SF are employees of Genentech, Inc., and hold Roche stock options.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaufman, P.A., Brufsky, A.M., Mayer, M. et al. Treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in elderly patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer from the registHER observational study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 135, 875–883 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2209-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2209-z