Abstract

We compared adherence to cART and virological response between indigenous and immigrant HIV-infected patients in the Netherlands, and investigated if a possible difference was related to a difference in the psychosocial variables: HIV-stigma, quality-of-life, depression and beliefs about medications. Psychosocial variables were assessed using validated questionnaires administered during a face-to-face interview. Adherence was assessed trough pharmacy-refill monitoring. We assessed associations between psychosocial variables and non-adherence and having detectable plasma viral load using logistic regression analyses. Two-hundred-two patients participated of whom 112 (55%) were immigrants. Viral load was detectable in 6% of indigenous patients and in 15% of the immigrants (P < 0.01). In multivariate analyses, higher HIV-stigma and prior virological failure were associated with non-adherence, and depressive symptoms, prior virological failure and non-adherence with detectable viral load. Our findings suggest that HIV-stigma and depressive symptoms may be targets for interventions aimed at improving adherence and virological response among indigenous and immigrant HIV-infected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HIV-infected patients have to take lifelong combination antiretroviral treatment (cART). To avoid treatment failure and development of resistant virus strains, high levels of adherence to cART are necessary [1, 2]. However, many HIV-infected patients have difficulties in maintaining sufficiently high levels of adherence to cART for long periods of time [3–5].

Nowadays, immigrant patients or patients from ethnic minority groups form a substantial part of the HIV-infected patient population in Western European countries [6]. Percentages of immigrants among newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients have been reported to range from 40 to 45% in these countries [7–10]. Studies conducted in Western European countries showed that virological and immunological failure on cART occurs more often in immigrants than in indigenous patients, with odds ratios ranging from 4.6 to 8.2 [7–9]. A possible explanation for this difference in response to cART may be a difference in adherence to cART [3, 11–15]. Several studies indeed found lower adherence to cART among immigrant populations [16–18].

The largest groups of immigrant HIV-infected patients in the Netherlands originate from Sub Sahara Africa, Surinam and the Dutch Antilles. Dutch immigrant patients were previously shown to have a worse virological response to cART compared to Dutch indigenous patients [8, 19]. A qualitative study showed that Dutch HIV-infected immigrants had low levels of quality of life, high levels of depressive symptoms and experienced or perceived high levels of HIV stigma [20]. Low levels of quality of life, and higher levels of HIV-stigma and depressive symptoms are known risk factors for lower levels of adherence to medication [21, 22] and specifically to cART [23–32]. In addition, doubts about the necessity of cART and concerns about adverse effects were previously found to predict non-adherence [33–35] and might be different among HIV-infected immigrant patients when compared with indigenous patients [36]. There is a marked difference in demographic characteristics between Dutch indigenous and immigrant patients. Immigrant patients predominantly have a heterosexual HIV transmission route and women form a substantial part [37]. Heterosexuals in general, and especially women, have been shown to experience more HIV-stigma and social isolation than white man who have sex with man (MSM), as they lack the supportive networks and the relative HIV/AIDS tolerant attitude, commonly experienced within the gay community [38].

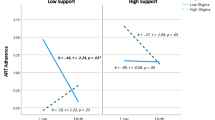

The aim of the present study is to compare adherence to cART and virological treatment response and various psychosocial risk factors for non-adherence, i.e., quality of life, depressive symptoms, HIV-stigma and beliefs about medication, between indigenous and immigrant HIV-infected patients in the Netherlands. We anticipated that these psychosocial risk factors may be more prevalent among immigrants, which may be associated with lower levels of adherence and consequently with a worse virological treatment response (see Fig. 1). Because heterosexuals in general, and especially woman, were previously shown to experience more HIV-stigma than white MSM, the influence of HIV transmission route and gender are also accounted for in the model. The second aim was to investigate to what extent psychosocial risk factors explain a potential difference in non-adherence and virological response to cART between indigenous and immigrant HIV-infected patients.

Methods

Participants

Between January 2008 and June 2009, adult non-pregnant HIV-1 infected patients were asked to participate in the present study at the outpatient HIV clinic of the Academic Medical Centre (AMC) in Amsterdam. Patients were eligible if they started cART after 1997, were on cART for at least 6 months, and had sufficient fluency in Dutch or English to participate in a face to face interview. Physicians or HIV counselling nurses invited eligible patients to participate following a planned regular consultation.

We aimed to recruit the following groups of HIV-infected patients: indigenous Dutch males and females with an HIV transmission route other than men who have sex with men (MSM), immigrant males and females with an HIV transmission route other than MSM who were born in Sub Sahara Africa, Surinam or the Dutch Antilles, and indigenous Dutch males with HIV transmission route being MSM. This latter group is the most prevalent at the HIV outpatient clinic of the AMC. Therefore, a random selection of this group of patients attending the outpatient clinic was invited to participate, to prevent oversampling of patients attending the clinic more often because of having more health problems and of those more willing to participate. We aimed to include 90 immigrant patients and 90 indigenous patients.

Patients signed an informed consent permitting the investigators to collect data from the patients’ medical files and to obtain information about refills of ARV medication at their pharmacies. We assessed quality of life, depressive symptoms, HIV-stigma, beliefs about medication and self-reported adherence using standard questionnaires that we administered during a face-to-face interview. The questionnaires were available in Dutch or English. Patients could choose in which language they wanted to be interviewed. The institutional review board of the AMC Amsterdam approved our study.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Data

From the medical files of participants, we obtained information about sex, age, HIV transmission route, immigrant origin (country of birth outside the Netherlands), prescribed ARV medication, type of ARV regimen (NNRTI based, PI based, NRTI based), instructed treatment interruptions, prior virological failure since starting cART, and plasma viral load results. The first viral load measure following the interview was retrieved. A detectable plasma viral load was defined as a load >40 copies HIV-RNA/ml. During the entire study period, the Abbott m2000rt HIV-1 assay was used.

Questionnaire

We obtained information about prescribed medication, prescribed number of pills per day and number of forgotten pills in the past month using self-report questions. We calculated adherence for each drug taken by the patient separately. We defined non-adherence as average adherence of all drugs being less than 100%.

We assessed quality of life using the overall quality of life subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey, i.e., ‘How has the quality of your life been during the past 4 weeks?’ [39]. Patients could answer on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘Very well’ to 5 = ‘Very bad’. Normally the scale scores are transformed to a range of 0 (worst quality of life) to 100 (best quality of life). However, in our study other psychosocial factors had scores with lowest scores meaning the best score and therefore in our study we used the scores of 1–5 without transforming them. Consequently, higher scores indicate a poorer quality of life.

We used the ‘beliefs about medication questionnaire’ to measure perceived necessity of cART (6 items) and perceived concerns about the potential adverse effects of cART (5 items) [34]. It employs a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘strongly’ agree to 5 = ‘strongly disagree’. Necessity items and concern items were summed and divided by the number of items producing one score for perceived necessity (range: 1–5) of cART and one score for concerns about adverse effects of cART (range: 1–6). Higher scores indicate low necessity or high concerns respectively.

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) consisting of 20 items such as ‘I felt that everything I did was an effort’ or ‘People were unfriendly’. Participants could answer on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = ‘rarely or none of the time’ to 3 = ‘Most or all of the time’. Item scores were summed to get a total score ranging from 0 to 60. We dichotomized the scores at the standard cut-off score of 15 with scores >15 being indicative of clinically significant depressive symptoms.

We measured personalized stigma and disclosure concerns with the Berger HIV stigma scale [40, 41]. Examples of items are ‘People don’t want me around their children once they know I have HIV’ for the personalized stigma scale and ‘Most people with HIV are rejected when others find out’ for the disclosure concerns scale. A four-point Likert-scale was used, ranging from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 4 = ‘strongly agree’. For each subscale, item scores were summed to obtain a personalized stigma score ranging from 18 to 72 and a disclosure concerns score ranging from 10 to 40 with higher scores indicating more perceived HIV-stigma.

Pharmacy Refill Adherence

In the Netherlands, each pharmacy has its own registration system and medication is typically dispensed every 90 days, although this period might vary from 1–3 months. For each medication refill, pharmacies record date of refill, collected number of medication, dosing instructions, prescription duration and prescriber. We sent a fax to each patient’s pharmacies to acquire the data of refilling each ARV medication for the entire period since the particular patient had started the current cART-regimen. Details about the collection of these data are described elsewhere [42].

We calculated refill adherence in the month prior to the interview. We chose this period because the self-report questions about adherence also ask about the previous month. We took into account leftover medication of former refills and instructed treatment interruptions as described previously [42].

For each period between refills we calculated adherence for each drug with the formula: leftover medication of former refills + collected medication at refill/prescribed medication per day/number of days between refills [43]. We calculated the average adherence of all drugs used (usually three). Adherence percentages could be higher than 100%, because of leftover medication and refilling before the final date of the prescribed treatment time. Therefore, we truncated the adherence percentages of each drug separately at 100% before averaging. We defined non-adherence as an average adherence <100%. We used the cut-off of <100% adherence to define non-adherence because we previously showed that this cut-off predicted plasma HIV RNA significantly and with a narrower confidence interval than other cut-offs [42].

Statistical Analyses

We calculated mean adherence based on self-report and on pharmacy refill data. Additionally, we calculated percentages of patients being non-adherent and having a detectable viral load. We calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for multi-item scales to assess their internal reliability. To investigate differences between indigenous and immigrant HIV-infected patients we conducted Student’s t-tests for continuous variables and Chi2-tests for categorical variables.

We conducted stepwise multivariate logistic regression analyses to investigate variables independently associated with non-adherence to cART and with having a detectable viral load, resulting in odds ratios (ORs) for non-adherence (<100% adherence) and ORs for a detectable viral load. Variables were kept in the model when significant at P < 0.05.

With the four step model suggested by Baron and Kenny [44], we investigated whether a possible relationship between immigrant origin and outcome (non-adherence and detectable viral load) was mediated by psychosocial risk factors. We therefore established if there were significant relationships between: (1) immigrant origin and outcome (non-adherence or detectable viral load), (2) immigrant origin and the potential mediating risk factor, and (3) between the potential mediating risk factor and outcome (non-adherence or detectable viral load). In the fourth step, we established if the significant association between immigrant origin and outcome (non-adherence or detectable viral load) was attenuated or disappeared after controlling for that particular risk factor. We investigated the statistical significance of the mediation effect using bootstrapping to calculate the 95% confidence intervals of this effect, as described elsewhere [45, 46]. If the 95% confidence interval does not include zero, the mediation effect is statistically significant at P < 0.05.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using a 6 months time frame for the pharmacy refill adherence to investigate whether using a longer time frame would lead to a difference in results.

Results

Participants

Two-hundred-one patients were included in our study. Table 1 displays the patient characteristics. Forty-five percent (n = 91) were female, HIV transmission route was MSM in 45 (22%) patients, and the median age was 43 (IQR: 37–49) years. A total of 112 patients (56%) originated from Sub Sahara Africa, Surinam or the Dutch Antilles. Eleven percent of the patients (n = 22) had a detectable viral load in the first measurement following the interview. The median plasma viral load was 126 (interquartile range: 60–3,201) copies/ml. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.80 for the necessity scale, 0.75 for the concerns scale, 0.90 for depressive symptoms, 0.94 for personalized stigma and 0.85 for disclosure concerns.

Differences Between Indigenous and Immigrant Patients

Table 1 shows differences between indigenous and immigrant HIV-infected patients. Immigrants were more often female (χ2 = 44.5, P = 0.01), were younger (t = −8.6, P = 0.01), had a shorter time since the first positive HIV test (t = −3.1, P = 0.01), more often had prior therapy failure (χ2 = 12.2, P < 0.01) and more often used a PI-based cART regimen (χ2 = 6.2, P < 0.01).

Mean self-reported adherence was 96% (SD = 14.7) among immigrant patients and 99% (SD = 9.8) among indigenous patients (t = −1.45, P = 0.15). Of the immigrant patients, 24% was non-adherent based on self-report, while this percentage was 11% for indigenous patients (χ2 = 5.5, P = 0.02). Mean pharmacy adherence was 89% (SD = 22) among immigrant patients and 95% (SD = 15) among indigenous patients (t = −2.3, P = 0.02). Of the immigrant patients, 37% was non-adherent based on pharmacy data while this percentage was 21% for indigenous patients (χ2 = 6.1, P = 0.01). Fifteen percent of the immigrant patients and 6% of indigenous patients had a detectable viral load (χ2 = 4.7, P = 0.03).

Immigrant patients reported significant poorer quality of life (t = 2.4, P = 0.01), and higher levels of depressive symptoms (t = 5.8, P < 0.01), personalized stigma (t = 7.9, P < 0.01) and disclosure concerns (t = 4.0, P < 0.01). Also, they reported more concerns about adverse effects of cART (t = 6.7, P < 0.01). There was no difference in doubts about the necessity of cART (t = 0.8, P = 0.4).

Factors Associated with Non-adherence

As pharmacy refill non-adherence was more strongly associated with a detectable viral load (OR = 4.9; 95% CI 1.9–12.5, P < 0.01) than self-reported non-adherence (OR = 3.0; 95% CI 1.1–7.7, P = 0.03), we only describe the results using pharmacy-refill adherence.

Table 2 shows univariate relationships of possible risk factors for pharmacy refill non-adherence (i.e., adherence <100%). Immigrant origin (OR = 2.2; 95% CI: 1.2–4.2, P = 0.01), personalized stigma (OR = 1.03; 95% CI: 1.0–1.1, P = 0.04) and disclosure concerns (OR = 1.1; 95% CI: 1.0–1.2, P = 0.02) were significantly related to pharmacy-refill non-adherence in univariate analyses. Using stepwise multivariate analyses, disclosure concerns (OR = 1.1; 95% CI: 1.01–1.2, P = 0.048) and prior virological failure (OR = 3.9; 95% CI: 1.3–9.7, P = 0.011) were independently related to pharmacy-refill non-adherence.

Because immigrant origin was significantly associated with non-adherence (see Table 2) and with disclosure concerns (see Table 1), and disclosure concerns with non-adherence (see Table 2), we investigated if the association between immigrant origin and non-adherence was mediated by disclosure concerns. The association between immigrant origin and non-adherence was attenuated, but remained statistically significant, after adjustment for disclosure concerns (OR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.0–3.7, P = 0.05). The mediation effect for disclosure concerns was statistically significant at P < 0.05 (beta value mediation effect estimate 0.21, 95% confidence interval: 0.02–0.50).

Factors Associated with Detectable Plasma Viral Load

Immigrant origin (OR = 3.0; 95% CI: 1.1–8.6, P = 0.04), prior virological failure (OR = 8.0; 95% CI: 2.8–22.7, P < 0.01), receiving a PI-based regimen (OR = 4.7; 95% CI: 1.7–12.5, P < 0.01), non-adherence (OR = 4.9; 95% CI 1.9–12.5, P < 0.01), worse quality of life (OR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.1–2.3, P = 0.02) and having clinically significant depressive symptoms (OR = 3.2; 95% CI: 1.3–8.0, P = 0.01) were significantly associated with having a detectable viral load in univariate analyses.

In the multivariate analysis, non-adherence (OR = 4.9; 95% CI: 1.8–13.8, P < 0.001), clinically significant depressive symptoms (OR = 3.3; 95% CI: 1.2–9.3, P = 0.02) and prior virological failure (OR = 5.6; 95% CI: 1.7–18.3, P = <0.001) remained significantly associated with detectable viral load.

Because immigrant origin was significantly associated with detectable viral load (see Table 3) and depressive symptoms (see Table 1), and depressive symptoms with detectable viral load (see Table 3), we investigated if the association between immigrant origin and detectable viral load was mediated by depressive symptoms. The significant association between immigrant origin and detectable viral load disappeared after adjustment for depressive symptoms (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 0.8–7.2, P = 0.11). The mediation effect for depressive symptoms was statistically significant at P < 0.05 (beta value mediation effect estimate 0.37, 95% confidence interval: 0.04–0.88).

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis in which we used a 6 months time frame instead of the 1 month time frame did not change the results. Immigrants still had significantly lower adherence than indigenous persons and the variables that were significantly associated with non-adherence and virological response remained the same.

Discussion

We found that immigrant patients had significantly lower levels of adherence to cART, an increased chance of having a detectable viral load, and higher levels of depressive symptoms and HIV-stigma than indigenous patients. The immigrant status per se was not independently associated with lower levels of adherence and virological outcome, but this association was mediated by other factors. The association between immigrant status and non-adherence was mediated by HIV-stigma. The association between immigrant status and detectable viral load was mediated by depressive symptoms. We believe our findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing adherence and virological response to cART among immigrant and indigenous patients should target HIV-stigma and depressive symptoms.

Our finding that immigrant HIV-infected patients had lower levels of adherence to cART is consistent with other studies [17, 47–49]. Moreover, a significantly higher percentage of immigrant HIV-infected patients had a detectable viral load. This is also consistent with findings from other studies [7, 17, 18]. Our findings corroborate the findings of a former qualitative study showing lower levels of quality of life and higher levels of depressive symptoms and HIV-stigma among HIV-infected immigrant patients than among indigenous patients in the Netherlands [19].

Pharmacy refill adherence was a stronger predictor of virological response than self-reported adherence. We assessed self-reported adherence during a face-to-face interview. Consequently, the discrepancy between pharmacy refill adherence and self-report in predicting virological response may have been due to social desirability bias [50]. Moreover, depressive symptoms may have served as source of reporting bias in self-reported adherence. This issue is the subject of ongoing research.

In contrast with previous studies [28–30, 51, 52], we found no significant association between depressive symptoms and adherence to cART. Remarkably, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with detectable viral load. This finding appears to be consistent with those from previous studies that revealed a relationship between depressive symptoms and HIV disease progression, independent of non-adherence [53–55]. These studies have suggested that biological factors (e.g., neuroendocrine, immunological) and behavioural factors, such as smoking status and health care use, might play a role in this relationship. Our finding that depressive symptoms are significantly associated with virological response independent of pharmacy refill adherence deserves further investigation: is this attributable to a physiological or behavioural mechanism or does it reflect limitations of our method used to assess medication adherence?

Our study has several limitations. In our sample, a relatively small percentage of patients had a detectable viral load, leading to limited statistical power to demonstrate associations with detectable viral load in a multivariate model. A second limitation is the fact that the psychosocial risk factors for non-adherence, i.e., HIV-stigma, depressive symptoms, beliefs about medication and quality of life yielded significant inter-correlations of moderate magnitude (data not shown). This may have hampered our ability to estimate the effect of individual predictors. This significant correlation among psychosocial risk factors may be the result of conceptual overlap and common method variance as they were all assessed using self-report. A third limitation is that we used self-report measures in two different language versions to assess quality of life, depressive symptoms and HIV-stigma among indigenous patients and immigrants with different countries of origin. The difference in psychosocial risk factors for non-adherence between immigrant and indigenous patients may therefore represent a true difference, but could also reflect in part a difference in cultural interpretation of the items. However, we believe these differences are true, because our results are in line with other studies that have reported higher stigma and depressive symptoms among non-indigenous patients or ethnic minority populations [19, 56]. Additionally, during the interviews we got the impression that patients gave similar meanings to items because they often explained their answers. Fourth, additional factors may be associated with non-adherence and a detectable viral load, such as health care costs. In the Netherlands, health insurance is obligatory and costs of cART are covered by all health insurance companies. Nevertheless, quite some of the immigrant patients mentioned difficulties in paying for transport to the hospital. Possibly, difficulties in paying for costs indirectly related to the use of cART may have contributed to the lower levels of adherence among our immigrant group. The fifth limitation is the timing of the measurements. Psychosocial risk factors for non-adherence and non-adherence were assessed at the same time point, and viral load was measured at a later point in time. Therefore, we could not predict non-adherence, but only investigate its associations with risk factors. A longitudinal study including a larger percentage of patients with detectable viral loads would allow for investigating all risk factors for non-adherence and detectable viral load simultaneously. The last limitation is the validity of measuring adherence through self-report and pharmacy refill adherence. Both methods have their limitations and do not assess actual pill ingestions, although both methods were significantly related to virological treatment response in the present study and in previous studies [3, 9, 57–59].

Our study has several strengths. We were able to include a large percentage of immigrant HIV-infected patients. These patients are often underrepresented in studies. We therefore could show that psychosocial factors are indeed different for immigrant patients in comparison with indigenous patients. Another strength is that we had nearly complete data of pharmacy refills, and our study was strengthened by the combination of different sources of information including patient-reported data, pharmacy refill data and laboratory results.

The main implication of our study is the suggestion that depressive symptoms and HIV-stigma may be targets for interventions aimed at improving adherence and virological response among indigenous and immigrant HIV-infected patients. Future studies should investigate which strategies are appropriate to decrease HIV-stigma and depressive symptoms, and whether reducing HIV-stigma and depressive symptoms among HIV-infected patients indeed improves their adherence to cART and their subsequent virological treatment response.

References

Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(7):939–41.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30.

Gross R, Yip B, Lo Re V III, Wood E, Alexander CS, Harrigan PR, et al. A simple, dynamic measure of antiretroviral therapy adherence predicts failure to maintain HIV-1 suppression. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(8):1108–14.

Cambiano V, Lampe FC, Rodger AJ, Smith CJ, Geretti AM, Lodwick RK, et al. Long-term trends in adherence to antiretroviral therapy from start of HAART. AIDS. 2010;24(8):1153–62.

Bruin Md, Hospers HJ, van Breukelen GJ, Kok G, Koevoets WM, Prins JM. Electronic monitoring-based counseling to enhance adherence among HIV-infected patients: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2010;29(4):421–8.

UNAIDS. Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2008; 2008.

van den Berg JB, Hak E, Vervoort SC, Hoepelman IM, Boucher CA, Schuurman R, et al. Increased risk of early virological failure in non-European HIV-1-infected patients in a Dutch cohort on highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2005;6(5):299–306.

Nellen JF, Wit FW, De WF, Jurriaans S, Lange JM, Prins JM. Virologic and immunologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in indigenous and nonindigenous HIV-1-infected patients in the Netherlands. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(4):943–50.

Dray-Spira R, Spire B, Heard I, Lert F. Heterogeneous response to HAART across a diverse population of people living with HIV: results from the ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S5–12.

Barry SM, Lloyd-Owen SJ, Madge SJ, et al. The changing demographics of new HIV diagnosis at a London centre from 1994 to 2000. HIV Med. 2002;3:129–34.

Grossberg R, Zhang Y, Gross R. A time-to-prescription-refill measure of antiretroviral adherence predicted changes in viral load in HIV. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1107–10.

Maggiolo F, Ravasio L, Ripamonti D, Gregis G, Quinzan G, Arici C, et al. Similar adherence rates favor different virologic outcomes for patients treated with nonnucleoside analogues or protease inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(1):158–63.

Martin M, del Cacho E, Codina C, Tuset M, de Lazzari E, Mallolas J, et al. Relationship between adherence level, type of the antiretroviral regimen, and plasma HIV type 1 RNA viral load: a prospective cohort study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24(10):1263–8.

Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, Maartens G. Adherence to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HIV therapy and virologic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(8):564–73.

Townsend ML, Jackson GL, Smith R, Wilson KH. Association between pharmacy medication refill-based adherence rates and cd4 count and viral-load responses: a retrospective analysis in treatment-experienced adults with HIV. Clin Ther. 2007;29(4):711–6.

Mannheimer S, Friedland G, Matts J, Child C, Chesney M. The consistency of adherence to antiretroviral therapy predicts biologic outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(8):1115–21.

Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, Castelli F, Narciso P, Noto P, et al. Correlates and predictors of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: overview of published literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 3):S123–7.

Singh N, Berman SM, Swindells S, Justis JC, Mohr JA, Squier C, et al. Adherence of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(4):824–30.

Nellen JF, Nieuwkerk PT, Burger DM, Wibaut M, Gras LA, Prins JM. Which method of adherence measurement is most suitable for daily use to predict virological failure among immigrant and non-immigrant HIV-1 infected patients? AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):842–50.

Nellen F, Bruin MD, Kreyenbroek M, Stronks K, Prins JM. Perceptions on HIV infection and treatment in ethnic Dutch and non-ethnic-Dutch HIV-1 infected patients: qualitative interview study. In: Nellen F, editor. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in non-indigenous patients in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam; 2007. p. 57–70.

Stutterheim SE, Pryor JB, Bos AE, Hoogendijk R, Muris P, Schaalma HP. HIV-related stigma and psychological distress: the harmful effects of specific stigma manifestations in various social settings. AIDS. 2009;23(17):2353–7.

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–7.

Holmes WC, Bilker WB, Wang H, Chapman J, Gross R. HIV/AIDS-specific quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(3):323–7.

Ammassari A, Murri R, Pezzotti P, Trotta MP, Ravasio L, De LP, et al. Self-reported symptoms and medication side effects influence adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(5):445–9.

Mahajan A, Sayles J, Patel V, Remien R, Sawires S, Ortiz D, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S67–79.

Whetten K, Reif S, Whetten R, Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, mental health, distrust, and stigma among HIV-positive persons: implications for effective care. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):531–8.

Cardarelli R, Weis S, Adams E, Radaford D, Vecino I, Munguia G, et al. General health status and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic Ill). 2008;7(3):123–9.

Horberg M, Silverberg M, Hurley L, Towner W, Klein D, Bersoff-Matcha S, et al. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(3):384–90.

Kacanek D, Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, Wanke C, Isaac R, Wilson IB. Incident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: a longitudinal analysis from the Nutrition for Healthy Living study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(2):266–72.

Vranceanu AM, Safren SA, Lu M, Coady WM, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, et al. The relationship of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression to antiretroviral medication adherence in persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(4):313–21.

Spire B, Duran S, Souville M, Leport C, Raffi F, Moatti JP. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) in HIV-infected patients: from a predictive to a dynamic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(10):1481–96.

Protopopescu C, Raffi F, Roux P, Reynes J, Dellamonica P, Spire B, et al. Factors associated with non-adherence to long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy: a 10 year follow-up analysis with correction for the bias induced by missing data. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(3):599–606.

der Kolk IM, Sprangers MA, Ende MV, Schreij G, Wolf FD, Nieuwkerk PT. Lower perceived necessity of HAART predicts lower treatment adherence and worse virological response in the ATHENA cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(4):460–2.

Horne R, Buick D, Fisher M, Leake H, Cooper V, Weinman J. Doubts about necessity and concerns about adverse effects: identifying the types of beliefs that are associated with non-adherence to HAART. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(1):38–44.

Horne R, Cooper V, Gellaitry G, Date HL, Fisher M. Patients’ perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence: the utility of the necessity-concerns framework. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(3):334–41.

Horne R, Graupner L, Frost S, Weinman J, Wright SM, Hankins M. Medicine in a multi-cultural society: the effect of cultural background on beliefs about medications. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(6):1307–13.

Gras L, Sighem Av, Smit C, Zaheri S, Schuitemaker H, Wolf Fd, et al. Monitoring of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection in the Netherlands: Report 2009. Amsterdam: HIV Monitoring Foundation; 2009.

Lichtenstein B, Laska MK, Clair JM. Chronic sorrow in the HIV-positive patient: issues of race, gender, and social support. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;16:27–38.

Wu AW, Revicki DA, Jacobson D, Malitz FE. Evidence for reliability, validity and usefulness of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV). Qual Life Res. 1997;6(6):481–93.

Berger B, Ferrans C, Lashley F. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29.

Bunn J, Solomon S, Miller C, Forehand R. Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: a reexamination of the HIV stigma scale. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(3):198–208.

de Boer IM, Prins JM, Sprangers MAG, Nieuwkerk PT. Using different calculations of pharmacy refill adherence to predict virological failure among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:635–40.

Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(1):105–16.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psych. 1986;51(6):1173–82.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF.: SPSS macro for multiple mediation written by Andrew F. Hayes. The Ohio State University. http://www.afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html. Accessed 8 Sept 2011.

Gerber BS, Cho YI, Arozullah AM, Lee SY. Racial differences in medication adherence: a cross-sectional study of Medicare enrollees. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8(2):136–45.

Schackman BR, Ribaudo HJ, Krambrink A, Hughes V, Kuritzkes DR, Gulick RM. Racial differences in virologic failure associated with adherence and quality of life on efavirenz-containing regimens for initial HIV therapy: results of ACTG A5095. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(5):547–54.

Simoni JM, Goggin K, Reynolds NR, Wilson IB, Remien R, Bangsberg DR, et al. Is race/ethnicity associated with ART adherence? Findings from the MACH14 Study. In: 5th international conference on HIV treatment adherence; 2010.

Nieuwkerk PT, der Kolk IM, Prins JM, Locadia M, Sprangers MA. Self-reported adherence is more predictive of virological treatment response among patients with a lower tendency towards socially desirable responding. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(6):913–6.

Starace F, Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, De LP, Izzo C, et al. Depression is a risk factor for suboptimal adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 3):S136–9.

Rao D, Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, et al. A structural equation model of HIV related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2011. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-9915-0.

Hartzell JD, Janke IE, Weintrob AC. Impact of depression on HIV outcomes in the HAART era. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(2):246–55.

Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001;285(11):1466–74.

Villes V, Spire B, Lewden C, Perronne C, Besnier JM, Garre M, et al. The effect of depressive symptoms at ART initiation on HIV clinical progression and mortality: implications in clinical practice. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(7):1067–74.

Emlet C. Experiences of stigma in older adults living with HIV/AIDS: a mixed-methods analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(10):740–52.

Nieuwkerk PT, Oort FJ. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and virologic treatment response: a meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(4):445–8.

Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks G, Crepaz N. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S23–35.

Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB. The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care. 2004;42(7):649–52.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who took part in this study. Also, we like to thank all HIV physicians and HIV counselling nurses of the Department of Internal Medicine of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, for asking patients to participate in our study. Lastly, we thank all interviewers and participating pharmacies. This study was supported by the Aids fund, Amsterdam, the Netherlands (grant 6003 and grant 2006013).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sumari-de Boer, I.M., Sprangers, M.A.G., Prins, J.M. et al. HIV Stigma and Depressive Symptoms are Related to Adherence and Virological Response to Antiretroviral Treatment Among Immigrant and Indigenous HIV Infected Patients. AIDS Behav 16, 1681–1689 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0112-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0112-y