Abstract

Objective

Helicobacter pylori infection is a common chronic infection that is closely associated with gastric cancer, known to be decreasing worldwide. We set up an administrative project of screening examination for H. pylori infection in junior high school students in Akita Prefecture to investigate the current prevalence of H. pylori infection in childhood in an area where the incidence of gastric cancer is particularly high.

Subjects and methods

All students in their second or third year of junior high school (13 to 15 years old) in two cities in Akita Prefecture were recruited. First, a urine-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of H. pylori antibody was performed. Then, a 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) was carried out in students who tested positive on the urinary test. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents.

Results

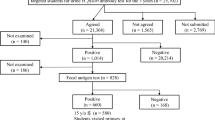

A total of 1813 students were recruited in this study; 1765 (97.3%) students agreed to participate in this project and underwent a screening examination. Among 96 students (5.4%) testing positive for H. pylori on the initial screening examination, 90 (93.7%, 90/96) underwent a subsequent 13C-UBT, and 85 (4.8%, 85/1765) were diagnosed as positive for H. pylori.

Conclusions

The current prevalence of H. pylori infection among students was low even in an area of Japan with a high incidence of gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a common chronic infection that has been confirmed to be significantly associated with gastric cancer [1–3]. The high prevalence of H. pylori infection and gastrointestinal disease in adults is closely related to H. pylori infection during childhood [4]. It also has been proved that eradication of H. pylori infection reduces the incidence of gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic Asian individuals [5] and that early-stage eradication is more effective than late-stage eradication to reduce such incidence in animal experiments [6]. Based on these studies, treatment of H. pylori infection in younger individuals is thought to be beneficial.

H. pylori infection occurs mainly during childhood, under the age of 5 years, and new infection in the teen years or later is rare [7, 8]. Although the infection route of this bacteria has not been clarified, its prevalence has dramatically decreased mainly in developed countries over the past decades, possibly because of the improvement of sanitation. Therefore, it is important to determine the current status of H. pylori infection in children to predict the future incidence of H. pylori-related diseases, including gastric cancer. which could be incorporated into a prevention strategy [9, 10]. However, the suitable method and age for screening examinations for H. pylori infection in childhood remain unclear.

We started this administrative project of screening examinations for H. pylori infection in junior high school students in Akita Prefecture in Japan. The aim was to investigate the current prevalence of H. pylori infection in childhood in an area where the incidence of gastric cancer is particularly high. The local government and our research group set up a public project for this cross-sectional study, and we evaluated the feasibility of our screening method.

Subjects and methods

This prospective study was performed in two cities adjacent to each other in Akita Prefecture: Yurihonjo City and Nikaho City. They are located in rural areas and have a population of 100,000 in total. There are 13 junior high schools with a total of approximately 3000 students in three year grades. Those in their second or third year in 2015, aged between 13 and 15 years, were selected for inclusion in this study.

Education through junior high school is compulsory in Japan, and all students undergo annual health checkups including urinalysis. After obtaining informed consent from students and their parents, this urine sample was used for the first screening examination using a urinary test (RAPIRAN; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan) to detect the anti-H. pylori antibody by immune chromatography. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of this test have been reported to be 89 and 93%, respectively [11, 12].

Then, students who tested positive for H. pylori on the urinary test were requested to visit Yuri Kumiai General Hospital where they underwent a medical interview and a 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT). The 13C-UBT was conducted on site at the hospital according to a previously validated method. Baseline breath samples were collected 4 h after a meal. Then, 13C-urea (100 mg) was administered to each subject, and a repeat breath sample was collected after 30 min. Samples were analyzed by using isotope-ratio mass spectrometry, and a positive result was defined by a cutoff value of 3.5%.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yuri-kumiai General Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents. This study is registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (No. UMIN000016926).

Statistical analysis

The associations between H. pylori infection and potential risk factors were evaluated using the χ 2 test, with P values of <0.05 considered significant. Statistical interpretation of data was performed using SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 1813 students (Yurihonjo City, 1348; Nikaho City, 465) were recruited in this study; 1765 (97.3%) students agreed to participate in this project and underwent the first screening examination. Ninety-six students (5.4%, 96/1765) tested positive for H. pylori on the urinary antibody test; 90 (93.7%, 90/96) underwent a subsequent 13C-UBT. Eighty-five of them (94.4%, 85/90) also tested positive for H. pylori on the 13C-UBT. This accounted for 4.8% of 1765 screened students (Fig. 1).

The rate of positive H. pylori results on the urinary antibody test was slightly higher in boys (6.3%, 56/894) than in girls (4.6%, 40/871), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.074). There was no difference in urinary antibody test results between school grades or cities (Table 1).

Discussion

Incidence and mortality rates of gastric cancer in Japan show some geographical variation, and those in the northeast area including Akita Prefecture are particularly high. The age-adjusted incidence and mortality rates of gastric cancer in Akita Prefecture in 2011 were 117.5 and 36.3 per 100,000 individuals, respectively, [13], which were well above the national average (80.4 and 27.4) and were the highest in Japan.

The prevalence of H. pylori infection in adults also shows geographic variation in Japan [14]. There is no report on such prevalence in Akita Prefecture, but in a study comparing seven Japanese regions (Hokkaido, Aomori, Yamagata, Gunma, Aichi, Shiga and Kagawa), Yamagata Prefecture, located just next to Akita Prefecture, showed the highest prevalence (54.5%). Thus, it could be postulated that H. pylori positivity in adults in Akita Prefecture is also high. In these situations, it is meaningful to investigate the accurate prevalence of H. pylori infection in children in this region.

There are already several reports on the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Japanese children ranging from 1.8% in Hyogo to 12% in Aomori (Supplement 1) [15–18]. The prevalence was generally lower in children than in adults [19, 20], reflecting the decreasing trend of infection over the past decades. However, those previous reports may have some selection bias because they did not include all children of a target age and/or area with relatively low participation rates. In our study, on the other hand, all students in their second or third year of junior high schools in two cities (representing all children in their generation in that area) were recruited with a very high participation rate in the two-step screening (urine test 97.3%; 13C-UBT 94.0%). Therefore, our results reflect an accurate infection rate of children with little bias in an area where the mortality rate of gastric cancer is high.

There is no consensus on the methods and age for screening of H. pylori infection in childhood. For adults, biopsy with histologic examination, urease test and culture has been widely used to directly detect the bacteria, but they are invasive and may show false-negative results in the cases of patchy colonization of the organism. Among noninvasive tests, accuracy of the urinary antibody test is reported to be similar to that of the serum-based test. The latter has been found to be less reliable in children than in adults. 13C-UBT has shown high accuracy in several studies in children, e.g., overall sensitivity and specificity of 97.8 and 98.5% with a cutoff value of 3.5% in the study by Kato et al. [21].

We used the urinary test as the first screening because urinary samples were available from all junior high school students because of the Japanese educational system. The sensitivity and specificity of this test (89 and 93%) were slightly lower than those of 13C-UBT, but its simplicity is a definite advantage over 13C-UBT for screening. We then used 13C-UBT in students who tested positive for H. pylori on the urinary test to confirm infection. The participation rate was very high in our study; thus, we can regard this 4.8% as the true prevalence of H. pylori in children between 13 and 15 years old in this area. This combination of urinary test and 13C-UBT in junior high school students seems to be an adequate method to determine the H. pylori infection rate in the young generation and can be used as nationwide screening at least in Japan and other countries having similar educational and health care systems.

In conclusion, the current prevalence of H. pylori infection among junior high school students in an area of Japan with a high incidence of gastric cancer was low at only 4.8%. This project showed the possibility of performing the screening of H. pylori infection in junior high school, which may lead eradication therapy for young people to prevent gastric cancer.

References

Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–6.

Kikuchi S, Wada O, Nakajima T, Nishi T, Kobayashi O, Konishi T, et al. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody and gastric carcinoma among young adults. Research Group on Prevention of Gastric Carcinoma among Young Adults. Cancer. 1995;75:2789–93.

Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–9.

Peterson WL GDY (2006) Helicobacter pylori. In: Feldman Sleisenger MH (ed) Sleiseneger and Ford trans gastrointestinal and liver disease; pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, 8th edn. WB Saundres Company, Philadelphia, pp 732–749.

Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication for the prevention of gastric neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD005583. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005583.pub2.

Nozaki K, Shimizu N, Ikehara Y, Inoue M, Tsukamoto T, Inada K, et al. Effect of early eradication on Helicobacter pylori-related gastric carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:235–9.

Rowland M, Daly L, Vaughan M, Higgins A, Bourke B, Drumm B. Age-specific incidence of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:65–72.

Okuda M, Miyashiro E, Booka M, Tsuji T, Nakazawa T. Helicobacter pylori colonization in the first 3 years of life in Japanese children. Helicobacter. 2007;12:324–7.

Gotoda T, Ishikawa H, Ohnishi H, Sugano K, Kusano C, Yokoi C, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing gastric cancer screening by gastrointestinal X-ray with serology for Helicobacter pylori and pepsinogens followed by gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:605–11.

Inoue M. Changing epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2016;. doi:10.1007/s10120-016-0658-5.

Yamamoto T, Ishii T, Kawakami T, Sase Y, Horikawa C, Aoki N, et al. Reliability of urinary tests for antibody to Helicobacter pylori in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:412–4.

Tamura T, Morita E, Kondo T, Ueyama J, Tanaka T, Kida Y, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection measured with urinary antibody in an urban area of Japan, 2008–2010. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2012;74:63–70.

Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan. http://ganjoho.jp/data/reg_stat/statistics/brochure/mcij2011_report.pdf#search=‘MCIJ2011’.

Ueda J, Gosho M, Inui Y, Matsuda T, Sakakibara M, Mabe K, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection by birth year and geographic area in Japan. Helicobacter. 2014;19:105–10.

Naito Y, Shimizu T, Haruna H, Fujii T, Kudo T, Shoji H, et al. Changes in the presence of urine Helicobacter pylori antibody in Japanese children in three different age groups. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:291–4.

Akamatsu T, Ichikawa S, Okudaira S, Yokosawa S, Iwaya Y, Suga T, et al. Introduction of an examination and treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in high school health screening. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1353–60.

Urita Y, Watanabe T, Kawagoe N, Takemoto I, Tanaka H, Kijima S, et al. Role of infected grandmothers in transmission of Helicobacter pylori to children in a Japanese rural town. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:394–8.

Okuda M, Osaki T, Lin Y, Yonezawa H, Maekawa K, Kamiya S, et al. Low prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a population-based study in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20:133–8.

Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M, Takeda H, Mitani S, Miyazaki T, et al. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:760–6.

Kikuchi S, Nakajima T, Kobayashi O, Yamazaki T, Kikuichi M, Mori K, et al. Effect of age on the relationship between gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori. Tokyo Research Group of Prevention for Gastric Cancer. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:774–9.

Kato S, Ozawa K, Konno M, Tajiri H, Yoshimura N, Shimizu T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the 13C-urea breath test for childhood Helicobacter pylori infection: a multicenter Japanese study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1668–73.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the considerable support of the public health nurses and all employees of both the local governments of Yurihonjo City and Nikaho City and the kind help of all the medical staff and assistants of Yuri Kumiai General Hospital, Akita, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Financial support

This project was supported by anticancer fund of Yurihonjo and Nikaho city.

Guarantor of the article

Chika Kusano, MD, PhD.

Human rights statement and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or a substitute for it was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kusano, C., Gotoda, T., Ishikawa, H. et al. The administrative project of Helicobacter pylori infection screening among junior high school students in an area of Japan with a high incidence of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 20 (Suppl 1), 16–19 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0688-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0688-7