Abstract

We investigated the prevalence and risk factors of vertebral fractures in Korea. In a community-based prospective epidemiology study, 1,155 men and 1,529 women (mean age 59 years, range 43–74) were recruited from Ansung, a rural Korean community. Prevalent vertebral fractures were identified on the lateral spinal radiographs at T11 to L4 using vertebral morphometry. Bone mineral density (BMD) was measured at the lumbar spine, femur neck and total hip. Of the 2,684 subjects, 137 (11.9%) men and 227 (14.8%) women had vertebral fractures and the standardized prevalence for vertebral fractures using the age distribution of Korean population was 8.8% in men and 12.6% in women. In univariate analysis, older age, low hip circumference, low BMD, low income and education levels in both sexes, previous history of fracture in men, high waist-to-hip circumference ratio, postmenopausal status, longer duration since menopause, and higher number of pregnancies and deliveries in women were associated with an increased risk of vertebral fractures. However, after adjusting for age, only low BMD in both sexes and a previous history of fracture in men were significantly associated with an increased risk of vertebral fractures. Vertebral fractures are prevalent in Korea as in other countries. Older age, low BMD and a previous history of fracture are significant risk factors for vertebral fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A vertebral fracture is one of the most common osteoporotic fractures and is also a major public health problem affecting millions of people worldwide [1, 2]. However, only one-third of patients with vertebral fractures seek medical attention, because most patients are asymptomatic and only notice when height loss or kyphosis is present [1]. Vertebral fractures can cause chronic back pain and functional impairment of daily activities. They are also associated with a decreased quality of life such as depression [3], and a 5-fold increased risk for subsequent vertebral and hip fractures as well as increased mortality [4, 5].

Early epidemiological studies on vertebral fractures revealed a wide variation in the prevalence ranging from 1% in Finland [6] to 25% in the USA [1, 7–11]. Vertebral fractures can be assessed by various methods using lateral spine radiographs. The wide variation in previous studies has, in part, resulted from the differences in measurement protocol. Therefore, recent epidemiological studies adopted the quantitative assessment [12] based on measurement of vertebral height with fixed cut-offs to define fractures. There have been several different approaches including the McCloskey method, the Melton method, the Eastell method and the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures [7, 13–15]. Although no single method has emerged as the gold standard, by using the same quantitative assessment method, it is possible to compare the prevalence of vertebral fractures from different populations. Using the Rochester method, the prevalence of vertebral fractures from different regions of the world has been reported to be approximately 16−21% [12, 13, 15]. Although the absolute prevalence varies, most of the studies showed that the prevalence of vertebral fractures increased significantly with age. In addition, low bone mineral density (BMD), low body mass index (BMI), previous vertebral fractures, alcohol ingestion, smoking, and decreased physical activity have been consistently reported to be associated with vertebral fractures [16–21].

Although the incidence of hip fractures, another severe consequence of osteoporosis, is lower in Asian countries compared to Western countries [22, 23], the prevalence of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women has been shown to be similar across different ethnic groups [24]. Using a national health insurance database, we previously reported the incidence of hip fracture in Korea to be 262.9/100,000 in women and 137.5/100,000 in men over the age of 50, respectively [25], which is very similar to other south-east Asian countries [22], but still lower than the incidence from Western countries. However, there has been no study investigating the prevalence of vertebral fractures in Korea. Understanding the descriptive epidemiology of vertebral fractures is important in estimating the overall public health burden associated with osteoporosis. Therefore, we studied the prevalence of vertebral fractures in Ansung County. We also investigated the risk factors associated with vertebral fractures.

Materials and methods

Study population and measurements

All subjects in the present study were recruited from the Ansung community cohort. Details of the Ansung cohort are described elsewhere [26, 27]. Ansung is a rural area located 75 km south of Seoul and more than half of the population live off agriculture. The Ansung cohort was established for a large-scale community-based epidemiological study of chronic diseases in Korea. The age distribution of the subjects is 32.0% in their 40’s, 29.4% in their 50’s, and 38.6% in their 60’s. The female proportion is 49.9%. The study commenced in 2001 with the enrollment of 5,020 subjects, aged ≥ 40 years. The subjects were subsequently examined every 2 years. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Korean Health and Genome Study.

During 2006–2007, 3,975 subjects (79.2%) had their 3rd follow-up visit. Of the 3,975 subjects, 2,950 subjects (1,289 men and 1,661 women) who had undergone lateral spine radiographs were included in this study. Of the 2,950 subjects, the radiographs of 266 (9.0%) were not suitable for analysis due to poor quality, inadequate penetration or poor positioning. Thus, the remaining radiographs of 2,684 (1,155 men and 1,529 women) were analyzed in this study.

Participants completed questionnaires via a face-to-face interview about demographics, previous medical history including fractures, menopausal status, alcohol ingestion, smoking, parental history of fractures, medication such as glucocorticoids, oral contraceptives, estrogen, or anti-diabetic drugs, and income and education levels.

Height and body weight were measured by standard methods in light clothes. BMI was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Waist circumference was measured at the narrowest point between the lower limit of the ribcage and the iliac crest and hip circumference (HC) was measured at the maximal extent of the buttocks. In 2,344 subjects (87.3%, 999 men and 1,345 women), the BMD of the lumbar spine, femur neck and total hip was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Lunar Prodigy, GE Healthcare).

Of the 2,684 subjects, 2,386 (88.9%) underwent a standard 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Blood samples for the measurement of plasma glucose and insulin were obtained at fasting, and at 60 and 120 min. Insulin was measured by using radioimmunoassay (Linco Research Inc.). The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated by the formula: fasting insulin (μIU/mL) × fasting blood glucose (mmol/mL)/22.5. C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured by immunoradiometry assay, as previously described [28].

Vertebral morphometry

Lateral spinal radiographs were performed with a tube-to-film distance of 105 cm according to a previously described protocol [29] and scanned from T11 to L4. The anterior (H a), middle (H m), and posterior (H p) height of each vertebral body from T11 to L4 were measured by a single trained technician (SMS). Normal population was classified as having no vertebral fracture by gross visual inspection and normal BMD as being within normal range for vertebral height and shape. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of ratio of normal vertebral height were obtained from 425 men and 398 women.

Definitions of vertebral fractures

To identify vertebral fractures, vertebral height (vertebral morphometry) was measured using the method of Eastell and colleagues [13]. In brief, we first calculated the anterior to posterior (H a/H p), middle to posterior (H m/H p) and posterior to posterior above and below (H pi/H pi+1 and H pi/H pi−1) ratios. Vertebral fracture was defined if any of the following ratios were more than 3 SDs below the normal mean for that vertebral level: (H a/H p), (H m/H p), or a combination of (H pi/H pi±1).

Statistical analysis

Numerical data are presented as mean ± SD. Age was evaluated in 10-year strata. BMD was evaluated per one SD decrease or categorized as normal, osteopenia, or osteoporosis depending on T scores. BMI was categorized into three groups, underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) or overweight (≥25 kg/m2). Waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), HOMA-IR, and CRP were evaluated in quartiles. Income status was divided into below or above 500,000 South Korean Won monthly. Educational status was divided into elementary, middle, or high school or college graduate. To evaluate the association between risk factors and prevalent vertebral fractures, we used logistic regression and chi-squared test (linear by linear association). All risk factors that were statistically significant in the univariate analyses were adjusted for age as a continuous variable by using multivariable logistic regression. All analyses were conducted separately for men and women. SPSS Version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis and p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Although only 2,684 subjects (67.5%) out of 3,975 subjects who had follow-up visits were analyzed in this study, there was no major difference in the general demographic characteristics between the studied subjects and the remaining 1,291 subjects (data not shown). Mean age of the study subjects was 59 in both men and women. The mean BMI was 23.8 kg/m2 in men and 25.0 kg/m2 in women.

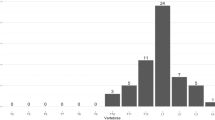

The crude prevalence of vertebral fractures was 11.9% (137/1,155) in men and 14.8% (227/1,529) in women. The standardized prevalence for vertebral fractures using the age distribution of the Korean population for the year 2006–2007 is 8.8% in men and 12.6% in women. The most commonly involved vertebral levels in men were T11 and T12, and those in women were T12 and L2.

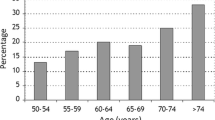

The risk of vertebral fractures increased with advancing age in both men and women (Table 2). The prevalence of vertebral fractures increased from 6.6% in 40–49 year olds to 20.1% in ≥70–year-old men and from 4.4% to 26.3% in ≥70-year-old women (p for trend < 0.01). A decreasing HC in both men and women and an increasing WHR in women were significantly associated with an increased risk for vertebral fracture (Table 2).

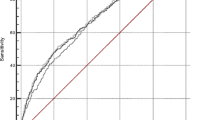

A decreasing BMD at all 3 measurement sites (lumbar spine, femur neck, or total hip) significantly increased the risk of vertebral fracture. When we classified the subjects based on the T score, subjects with a T score ≤ −2.5 had a higher prevalence of vertebral fractures than the others, as expected. However, the greatest number of fractures was observed in the normal BMD group (58 cases) in men and the osteopenia group (91 cases) in women. BMD at the femur neck or total hip tended to have a stronger relationship with vertebral fractures than lumbar BMD.

A previous history of fracture was also associated with an increased risk of vertebral fractures in men (OR 2.288, CI 1.171–4.469). In women, current drinkers had fewer vertebral fractures (OR 0.659, CI 0.461–0.943) but the amount of alcohol intake was not significantly associated with risk of vertebral fractures in both sexes (data not shown). In women, ex-smokers showed an increased risk of vertebral fractures, but the number of ex-smokers was only 12. Interestingly, subjects who had more income and a higher education level were less likely to have vertebral fractures in both men and women.

In this study, 79.5% of women had reached menopause. Postmenopausal women had a higher prevalence of vertebral fractures than premenopausal women (OR 3.532, CI 2.088–5.973). In addition, a longer duration since menopause was significantly associated with increased risk of vertebral fracture (OR 3.185, CI 2.115–4.795), while age at menopause or menarche was not. An increased number of deliveries (OR 2.011, CI 1.502–2.692) and an increased number of pregnancies (OR 2.553, CI 1.157–2.083) were associated with an increased risk of vertebral fractures.

Among 2,386 subjects, 175 (15.2%) men and 228 (14.9%) women were diagnosed as having diabetes, however, the presence of diabetes was not associated with a risk of vertebral fracture nor was HOMA-IR, an insulin-resistant parameter. CRP, a marker of inflammation was also not associated with risk of fracture.

Although advancing age, low HC, low BMD, low income and education level in both sexes, previous history of fracture in men and high WHR, postmenopausal state, longer duration since menopause, and increased number of pregnancies and deliveries in women were associated with an increased risk of vertebral fractures, only low BMD in both sexes and a previous history of fracture in men remained significant risk factors for vertebral fractures after adjusting for age (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first population-based study to evaluate the prevalence of vertebral fractures in Korea. Vertebral fractures were evaluated in 2,684 subjects from the Ansung community cohort and the prevalence of vertebral fractures was 11.9% in men and 14.8% in women aged ≥ 40 years. The standardized prevalence of vertebral fractures using the age distribution from the Korean population is 8.8% in men and 12.6% in women.

The prevalence of vertebral fractures in this study is similar to other studies from various ethnic groups and countries which used the same methods (Table 4) [12, 13, 15]. Previous studies have also demonstrated that the prevalence of vertebral fractures in Asian countries is similar to Western countries [24]. The similar prevalence of vertebral fractures in this study is in contrast with the fact that the incidence of hip fracture in Korea is lower than Western or some Asian countries [24]. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear; however, one potential speculation may be related to the different pathogenesis between vertebral fracture and hip fracture. While hip fractures are almost always associated with trauma and fall, vertebral fractures are associated more with low BMD [30, 31]. In a recent study, we found that the BMD in both Korean men and women > 50 years was significantly lower compared to African-American or Mexican Americans [32]. Therefore, the disproportionate epidemiology of vertebral versus hip fractures in Koreans may originate from the relatively lower BMD with resultant low mechanical strength.

A previous history of fracture was significantly associated with prevalent vertebral fractures only in men. Considering that the questionnaire-based fracture history would be mostly comprised of long bone fracture, it may imply that risk factors for long bone and vertebral fracture are different; long bone fractures being mostly related to the propensity to fall while vertebral fractures are more related to low bone mass.

Notably, we found that low income level was significantly associated with vertebral fracture in univariate analysis. Our results are in good agreement with previous studies that observed a similar association between poverty and osteoporosis [33, 34]. It is believed that people with a higher socioeconomic status are in better nutritional condition and have easier access to health resources, which could contribute to maintaining better skeletal health [35]. However, income and education level did not show an association with vertebral fracture in multivariate analysis. This may be caused by the generation gap in Korea. Because Korea has developed very quickly, older adults usually have smaller income and a lower level of education.

Many clinical risk factors including BMI, alcohol intake and smoking which are known to be associated with vertebral fractures in studies from other ethnic groups had little or no influence on vertebral fractures in this study. Since alcohol intake and smoking were not associated with BMD in this cohort either [32], it may be reasonable to expect that the bone response to specific risk factors may be different depending on the ethnicity [12, 36].

We unexpectedly found that a lower HC in both sexes and a higher WHR in women were significantly associated with an increased risk for vertebral fracture in univariate analysis. A previous study on this cohort revealed a higher HC to be negatively associated with an incidence of non-vertebral fractures but not with vertebral fractures [37]. The discrepancy with our data in regard to vertebral fracture may originate from the difference in defining vertebral fracture because the previous study identified vertebral fracture as based on more than 4 cm of height loss, which would detect only severe cases. Since a smaller HC is associated with a smaller pelvis size and reduced gluteofemoal muscle or fat mass [38], it may be plausible to expect that a higher HC could provide a better cushioning effect against fall-related fractures. However, the association between HC and vertebral fracture is difficult to explain. We speculate that although vertebral fracture is mostly related to BMD rather than fall risk, the higher HC could also prevent minor fall-related collapsed vertebrae. Alternatively, as the HC has been shown to be correlated with quantitative ultrasound parameters [39], it is possible that HC may be one of the surrogate markers of bone quality. In addition, WHR has been correlated with serum testosterone level [40] suggesting these regional adiposity indices may reflect metabolic aspects of bone health status. The mechanistic insight into the association between anthropometric parameters and fracture risk should be further determined.

We found that older age, low HC, low BMD, low educational and income levels in both sexes, previous history of fracture in men, and high WHR, postmenopausal status, longer duration since menopause, and increased number of pregnancies and deliveries in women are potential risk factors for vertebral fractures. However, after adjusting for age, only low BMD in both sexes and a previous history of fracture in men are associated with an increased risk of vertebral fractures. Our results are consistent with the belief that low BMD is the most important determinant of vertebral fracture. This observation has a clinical implication in that vertebral fractures can be effectively prevented by early diagnosis of osteoporosis using DXA screening in subjects with potential risks. This is especially true in Korea, because in this study of 420 subjects who had osteoporosis, only 155 (36.9%) were aware of having osteoporosis and only 73 (17.4%) had received treatment for osteoporosis (data not shown).

The prevalence of vertebral fractures was higher in subjects with osteoporosis compared to those with osteopenia or normal BMD as expected. However, the greatest number of fractures occurred in men with normal BMD and in women with osteopenia because these groups contained many more subjects with BMD. These data are in full agreement with the results of National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment study [41] and underscore the importance of early screening and appropriate management of people with osteopenia and also people with normal BMD who have risk factors.

The main limitation of our study is that we measured only six vertebrae while vertebrae from T4 to L4 were assessed in other studies. Previous studies showed that fractures in levels T4–T10 comprise 30–50% of all fractures [15, 42]. Therefore, the actual prevalence of vertebral fractures may be more than double what we have reported in this study. However, the distribution of vertebral fractures in Asian populations may be different from Western countries and further studies are needed. Another limitation is that this study was conducted in a rural area, which may preclude the generalization of our data to the whole Korean population. Finally, since only 4 women (0.3%) were classified as having rheumatoid arthritis and the number of subjects taking glucocorticoid or estrogen was too small, we could not precisely estimate the effect of these well-established risk factors.

In conclusion, the prevalence of vertebral fractures (T11 to L4) in Korea is approximately 8.8% in men and 12.6% in women. Older age and low BMD in both sexes and a previous history of fracture in men are the most important risk factors for vertebral fractures in Korea.

References

Cooper C, O’Neill T, Silman A (1993) The epidemiology of vertebral fractures. Bone 14:89–97

Melton LJI (1997) Epidemiology of spinal osteoporosis. Spine 22:2S–11S

Lips P, Cooper C, Agnusdei D, Caulin F, Egger P, Johnell O, Kanis JA, Kellingray S, Leplege A, Liberman UA, McCloskey E, Minne H, Reeve J, Reginster JY, Scholz M, Todd C, de Vernejoul MC, Wiklund I (1999) Quality of life in patients with vertebral fractures: validation of the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO). Working Party for Quality of Life of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 10:150–160

Jalava T, Sarna S, Pylkkanen L, Mawer B, Kanis JA, Selby P, Davies M, Adams J, Francis RM, Robinson J, McCloskey E (2003) Association between vertebral fracture and increased mortality in osteoporotic patients. J Bone Miner Res 18:1254–1260

Kado DM, Browner WS, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Cummings SR (1999) Vertebral fractures and mortality in older women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med 159:1215–1220

Harma M, Heliovaara M, Aromaa A, Knekt P (1986) Thoracic spine compression fractures in Finland. Clin Orthop Relat Res 188–194

Melton LJ 3rd, Lane AW, Cooper C, Eastell R, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL (1993) Prevalence and incidence of vertebral deformities. Osteoporos Int 3:113–119

O’Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Varlow J, Cooper C, Kanis JA, Silman AJ (1996) The prevalence of vertebral deformity in European men and women: the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 11:1010–1018

Davies KM, Stegman MR, Heaney RP, Recker RR (1996) Prevalence and severity of vertebral fracture: the Saunders County Bone Quality Study. Osteoporos Int 6:160–165

Kitazawa A, Kushida K, Yamazaki K, Inoue T (2001) Prevalence of vertebral fractures in a population-based sample in Japan. J Bone Miner Metab 19:115–118

Tracy JK, Meyer WA, Grigoryan M, Fan B, Flores RH, Genant HK, Resnik C, Hochberg MC (2006) Racial differences in the prevalence of vertebral fractures in older men: the Baltimore Men’s Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 17:99–104

Ling X, Cummings SR, Mingwei Q, Xihe Z, Xioashu C, Nevitt M, Stone K (2000) Vertebral fractures in Beijing, China: the Beijing Osteoporosis Project. J Bone Miner Res 15:2019–2025

Eastell R, Cedel SL, Wahner HW, Riggs BL, Melton LJ 3rd (1991) Classification of vertebral fractures. J Bone Miner Res 6:207–215

McCloskey EV, Spector TD, Eyres KS, Fern ED, O’Rourke N, Vasikaran S, Kanis JA (1993) The assessment of vertebral deformity: a method for use in population studies and clinical trials. Osteoporos Int 3:138–147

Black DM, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Epstein R, San Valentin R, Cummings SR (1995) Comparison of methods for defining prevalent vertebral deformities: the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res 10:890–902

Van der Klift M, de Laet CE, McCloskey EV, Johnell O, Kanis JA, Hofman A, Pols HA (2004) Risk factors for incident vertebral fractures in men and women: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res 19:1172–1180

Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, Cauley JA, Ensrud K, Browner WS, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR (2003) BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res 18:1947–1954

Van der Klift M, De Laet CE, McCloskey EV, Hofman A, Pols HA (2002) The incidence of vertebral fractures in men and women: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res 17:1051–1056

Ross PD, Davis JW, Epstein RS, Wasnich RD (1991) Pre-existing fractures and bone mass predict vertebral fracture incidence in women. Ann Intern Med 114:919–923

Black DM, Arden NK, Palermo L, Pearson J, Cummings SR (1999) Prevalent vertebral deformities predict hip fractures and new vertebral deformities but not wrist fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res 14:821–828

Samelson EJ, Hannan MT, Zhang Y, Genant HK, Felson DT, Kiel DP (2006) Incidence and risk factors for vertebral fracture in women and men: 25-year follow-up results from the population-based Framingham study. J Bone Miner Res 21:1207–1214

Lau EM, Lee JK, Suriwongpaisal P, Saw SM, Das De S, Khir A, Sambrook P (2001) The incidence of hip fracture in four Asian countries: the Asian Osteoporosis Study (AOS). Osteoporos Int 12:239–243

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2004) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:897–902

Kung AW (2004) Epidemiology and diagnostic approaches to vertebral fractures in Asia. J Bone Miner Metab 22:170–175

Lim S, Koo BK, Lee EJ, Park JH, Kim MH, Shin KH, Ha YC, Cho NH, Shin CS (2008) Incidence of hip fractures in Korea. J Bone Miner Metab 26:400–405

Shin C, Abbott RD, Lee H, Kim J, Kimm K (2004) Prevalence and correlates of orthostatic hypotension in middle-aged men and women in Korea: the Korean Health and Genome Study. J Hum Hypertens 18:717–723

Cho NH, Jang HC, Choi SH, Kim HR, Lee HK, Chan JC, Lim S (2007) Abnormal liver function test predicts type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective study. Diabetes Care 30:2566–2568

Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, Fischer HG, Lowel H, Doring A, Hutchinson WL, Pepys MB (1999) C-Reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: results from the MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation 99:237–242

Kiel D (1995) Assessing vertebral fractures. National Osteoporosis Foundation Working Group on Vertebral Fractures. J Bone Miner Res 10:518–523

Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, Cauley J, Black D, Vogt TM (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med 332:767–773

Chapurlat RD, Bauer DC, Nevitt M, Stone K, Cummings SR (2003) Incidence and risk factors for a second hip fracture in elderly women. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Osteoporos Int 14:130–136

Shin CS, Choi HJ, Kim MJ, Kim JT, Yu SH, Koo BK, Cho HY, Cho SW, Kim SW, Park YJ, Jang HC, Kim SY, Cho NH (2010) Prevalence and risk factors of osteoporosis in Korea: a community-based cohort study with lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density. Bone 47:378–387

Yang K, McElmurry BJ, Park CG (2006) Decreased bone mineral density and fractures in low-income Korean women. Health Care Women Int 27:254–267

Pearson D, Taylor R, Masud T (2004) The relationship between social deprivation, osteoporosis, and falls. Osteoporos Int 15:132–138

Navarro MC, Sosa M, Saavedra P, Lainez P, Marrero M, Torres M, Medina CD (2009) Poverty is a risk factor for osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 20:393–398

Clark P, Cons-Molina F, Deleze M, Ragi S, Haddock L, Zanchetta JR, Jaller JJ, Palermo L, Talavera JO, Messina DO, Morales-Torres J, Salmeron J, Navarrete A, Suarez E, Perez CM, Cummings SR (2009) The prevalence of radiographic vertebral fractures in Latin American countries: the Latin American Vertebral Osteoporosis Study (LAVOS). Osteoporos Int 20:275–282

Lee SH, Khang YH, Lim KH, Kim BJ, Koh JM, Kim GS, Kim H, Cho NH (2010) Clinical risk factors for osteoporotic fracture: a population-based prospective cohort study in Korea. J Bone Miner Res 25:369–378

Seidell JC, Perusse L, Despres JP, Bouchard C (2001) Waist and hip circumferences have independent and opposite effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Quebec Family Study. Am J Clin Nutr 74:315–321

Babaroutsi E, Magkos F, Manios Y, Sidossis LS (2005) Lifestyle factors affecting heel ultrasound in Greek females across different life stages. Osteoporos Int 16:552–561

Svartberg J, von Muhlen D, Sundsfjord J, Jorde R (2004) Waist circumference and testosterone levels in community dwelling men. The Tromso study. Eur J Epidemiol 19:657–663

Siris ES, Miller PD, Barrett-Connor E, Faulkner KG, Wehren LE, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM (2001) Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA 286:2815–2822

Lunt M, O’Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Reeve J, Kanis JA, Cooper C, Silman AJ (2003) Characteristics of a prevalent vertebral deformity predict subsequent vertebral fracture: results from the European Prospective Osteoporosis Study (EPOS). Bone 33:505–513

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Genome Research Institute, the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention (contract #2001–2003-348-6111-221, 2004-347-6111-213 and 2005-347-2400-2440-215).

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

C. S. Shin and M. J. Kim contributed equally to this work.

About this article

Cite this article

Shin, C.S., Kim, M.J., Shim, S.M. et al. The prevalence and risk factors of vertebral fractures in Korea. J Bone Miner Metab 30, 183–192 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-011-0300-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-011-0300-x