Abstract

Summary

In the present prospective controlled observational study, we investigated the effect of a coordinated intervention program on 4-year refracture rates in patients with recent osteoporotic fractures. Compared to standard care, targeted identification, and management significantly reduced the risk of refracture by more than 80%.

Introduction

The risk of refracture following an incident osteoporotic fracture is high. Despite the availability of treatments that reduce refracture and mortality rates, most patients with minimal trauma fracture (MTF) are not managed appropriately. The present prospective controlled observational study investigated the effect of a coordinated intervention program on 4-year refracture rates and time to refracture in patients with recent osteoporotic fractures.

Methods

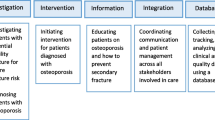

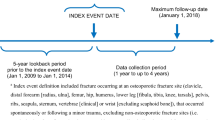

Patients presenting with a non-vertebral MTF were actively identified and offered referral to a dedicated intervention program. Patients attending the clinic underwent a standardized set of investigations, were treated as indicated and reviewed at 12-monthly intervals (‘MTF group’). Patients who elected to follow-up with their primary care physician were assigned to the concurrent control group.

Results

Groups were balanced for baseline anthropometric, socio-economic, and clinical risk factors. Over 4 years, 10 out of 246 patients (4.1%) in the MTF group and 31 of 157 patients (19.7%) in the control group suffered a new fracture, with a median time to refracture of 26 and 16 months, respectively (p < 0.01). Compared to the intervention group, the risk of refracture was increased by 5.3-fold in the control group (95% CI: 2.8–12.2, p < 0.01), and remained elevated (HR 5.63, 95%CI 2.73–11.6, p < 0.01) after adjustment for other significant predictors of refracture such as age and body weight.

Conclusions

In patients presenting with a minimal trauma non-vertebral fracture, active identification and management significantly reduces the risk of refracture (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN 12606000108516).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1726–1733

Sambrook PN, Seeman E, Phillips SR, Ebeling PR. (2002) Osteoporosis Australia; National Prescribing Service. Preventing osteoporosis: outcomes of the Australian Fracture Prevention Summit. Med J Aust 15 (176): Suppl: S1–16.

NOF (2002) America's bone health: the state of osteoporosis and low bone mass in our nation.

Schneider EL, Guralnik JM (1990) The aging of America. Impact on health care costs. JAMA 263:2335–2340

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al (2000) Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmo. Osteoporos Int 11:669–674

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH et al (2007) Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22:465–475

Keene GS, Parker MJ, Pryor GA (1993) Mortality and morbidity after hip fractures. BMJ 307(6914):1248–1250

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR (2009) Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA 301:513–521

Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Olszynski WP et al (2002) The impact of incident vertebral and non-vertebral fractures on health related quality of life in postmenopausal women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 3(11):1471–2474

Kado DM, Duong T, Stone KL, Ensrud KE, Nevitt MC, Greendale GA, Cummings SR (2003) Incident vertebral fractures and mortality in older women: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 14:589–594

Johnell O, Oden A, Caulin F, Kanis JA (2001) Acute and long-term increase in fracture risk after hospitalization for vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 12(3):207–214

Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C et al (2001) Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA 285(3):320–323

Ross PD, Davis JW, Epstein RS, Wasnich RD (1991) Pre-existing fractures and bone mass predict vertebral fracture incidence in women. Ann Intern Med 114:919–923

Black DM, Arden NK, Palermo L et al (1999) Prevalent vertebral deformities predict hip fractures and new vertebral deformities but not wrist fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res 14:821–828

Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA (2007) Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. JAMA 297:387–394

Kleerekoper M, Gold DT (2008) Osteoporosis prevention and management: an evidence-based review. Clin Obstet Gynecol 51:556–563

Bliuc D, Ong CR, Eisman JA, Center JR (2005) Barriers to effective management of osteoporosis in moderate and minimal trauma fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 16:977–982

Panneman MJ, Lips P, Sen SS, Herings RM (2004) Undertreatment with anti-osteoporotic drugs after hospitalization for fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:120–124

Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Cranney A, Zytaruk N, Adachi JD (2006) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Semin Arthritis Rheum 35:293–305

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2000) How fragile is her future? Available at: http://www.iofbonehealth.org/facts-and-statistics.html. Accessed 15 Aug 2010

Rochat S, Cumming RG, Blyth F et al (2010) Frailty use health community services by community dwelling older men Concord Health Ageing Men Proj Age Ageing 39:228–233

New South Wales Agency for Clinical Innovation (2009) New South Wales re-fracture admission data 2002–2008. Available at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/resources/gmct/musculoskeletal/refracture_data_analysis_2009_pdf.asp. Accessed 15 Aug 2010

Premaor MO, Pilbrow L, Tonkin C, Adams M, Parker RA, Compston J (2010) Low rates of treatment in postmeno-pausal women with a history of low trauma fractures: results of audit in a Fracture Liaison Service. QJM 103:33–40

Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, CaMos Research Group et al (2008) The osteoporosis care gap in men with fragility fractures: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 19:581–587

Vaile J, Sullivan L, Bennett C, Bleasel J (2007) First Fracture Project: addressing the osteoporosis care gap. Intern Med J 37:717–720

Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L, CaMos Research Group et al (2009) Health-related quality of life in Canadian adolescents and young adults: normative data using the SF-36. Can J Public Health 100:449–52

Zethraeus N, Borgstrom F, Strom O, Kanis JA, Jonsson B (2007) Cost-effectiveness of the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis: a review of the literature and a reference model. Osteoporos Int 18:9–23

Feldstein A, Elmer PJ, Smith D et al (2006) Electronic medical record reminder improves osteoporosis management after a fracture: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 54:450–457

Harrington JT (2005) Redesigning the care of fragility fracture patients to improve osteoporosis management: a health care improvement project. Arthr Rheum 53(2):198–204

Chevalley T, Hoffmeyer P, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R (2002) An osteoporosis clinical pathway for the medical management of patients with low-trauma fracture. Osteoporos Int 13(6):450–455

Jaglal S, Cameron C, Hawker G et al (2006) Development of an integrated-care delivery model for post-fracture care in Ontario, Canada. Osteoporos Int 17:1337–1345

Hawker G, Ridout R, Ricupero M, Jaglal S, Bogoch E (2003) The impact of a simple fracture clinic intervention in improving the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int 14(2):171–178

Bliuc D, Eisman JA, Center JR (2006) A randomized study of two different information-based interventions on the management of osteoporosis in minimal and moderate trauma fractures. Osteoporos Int 17(9):1309–1317

Solomon DH, Polinski JM, Stedman M et al (2007) Improving care of patients at-risk for osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Int Med 22(3):362–367

Dell R, Greene D, Schelkun SR, Williams K (2008) Osteoporosis disease management: the role of the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 4:188–194

Kuo I, Ong C, Simmons L, Bliuc D, Eisman J, Center J (2007) Successful direct intervention for osteoporosis in patients with minimal trauma fractures. Osteoporos Int 18:1633–1639

McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C (2003) The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 14(12):1028–1034

Charalambous CP, Mosey C, Johnstone E et al (2009) Improving osteoporosis assessment in the fracture clinic. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 91:596–598

Chong C, Christou J, Fitzpatrick K, Wee R, Lim WK (2008) Description of an orthopedic–geriatric model of care in Australia with 3-year data. Geriatr Gerontol Int 8:86–92

Murray AW, McQuillan C, Kennon B, Gallacher SJ (2005) Osteoporosis risk assessment and treatment intervention after hip or shoulder fracture. A comparison of two centres in the United King dom. Injury 36:1080–1084

Harrington JT, Lease J (2007) Osteoporosis disease management for fragility fracture patients: new understandings based on three years' experience with an osteoporosis care service. Arthritis Rheum 57:1502–1506

Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse RG, Murray TM (2006) Effective initiation of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:25–34

Cauley JA, Lui LY, Ensrud KE et al (2005) Bone mineral density and the risk of incident nonspinal fractures in Black and White women. JAMA 293:2102–2108

Cummings S, Nevitt M, Browner W et al (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med 332:767–773

Nguyen ND, Frost SA, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2008) Development of prognostic nomograms for individualizing 5-year and 10-year fracture risks. Osteoporos Int 19:1431–1444

Berry SD, Samelson EJ et al (1971) Second hip fracture in older men and women: the Framingham Study. Arch Int Med 167(18):1971–1976

Langridge CR, McQuillian C, Watson WS, Walker B, Mitchell L, Gallacher SJ (2007) Refracture following fracture liaison service assessment illustrates the requirement for integrated falls and fracture services. Calc Tissue Intl 81:85–91

Hodsman AB, Leslie WD, Tsang JF, Gamble GD (2008) 10-year probability of recurrent fractures following wrist and other osteoporotic fractures in a large clinical cohort. Arch Int Med 168:2261–2267

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Odén A et al (2004) Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:175–179

Langsetmo LA, Morin S, Richards JB, CaMos Research Group et al (2009) Effectiveness of antiresorptives for theprevention of nonvertebral low-trauma fractures in a population-based cohort of women. Osteoporos Int 20:283–290

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ et al (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and non-vertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022

Reid IR, Mason B, Horne A, Ames R et al (2006) Randomized controlled trial of calcium in healthy older women. Am J Med 119(9):775–785

Prince RL, Devine A, Dhaliwal SS, Dick IM (2006) Effects of calcium supplementation on clinical fracture and bone structure: results of a 5-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in elderly women. Arch Intern Med 166:869–875

Porthouse J, Cockayne S, King C et al (2005) Randomised controlled trial of calcium and supplementation with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) for prevention of fractures in primary care. BMJ 330(7498):1003–1006

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kathy Wu, Veena Jayadev and Rohit Rajagapal, Mrs Bev White and Ms Lynley Robinson, and Klaus Sommer, CNC, and his team for their invaluable assistance with this study. We are particularly indebted to Professors David Handelsman and Jackie Center for their insightful comments and statistical advice. We are grateful for the co-operation of our colleagues at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, the Orthogeriatric Service, the Emergency Department (all at CRGH), and the patients’ primary care physicians.

The MTF program was supported by logistic support from Concord Repatriation General Hospital, by a Research Entry Grant from Osteoporosis Australia/The Royal Australasian College of Physicians, and by unrestricted research and educational grants from Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis Pharma, and MSD Merck Sharp & Dohme Pharmaceuticals, Australia.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lih, A., Nandapalan, H., Kim, M. et al. Targeted intervention reduces refracture rates in patients with incident non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures: a 4-year prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int 22, 849–858 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1477-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1477-x