Abstract

Background

Alcohol consumption is associated with a range of health and social harms that increase with the level of consumption. Policy makers are interested in effective and cost-effective interventions to reduce alcohol consumption and associated harms. Economic theory and research evidence demonstrate that increasing price is effective at the population level. Price interventions that target heavier consumers of alcohol may be more effective at reducing alcohol-related harms with less impact on moderate consumers. Minimum pricing per unit of alcohol has been proposed on this basis but concerns have been expressed that ‘moderate drinkers of modest means’ will be unfairly penalized. If those on low incomes are disproportionately affected by a policy that removes very cheap alcohol from the market, the policy could be regressive. The effect on households’ budgets will depend on who currently purchases cheaper products and the extent to which the resulting changes in prices will impact on their demand for alcohol. This paper focuses on the first of these points.

Objective

This paper aims to identify patterns of purchasing of cheap off-trade alcohol products, focusing on income and the level of all alcohol purchased.

Method

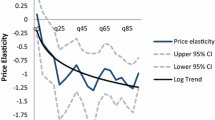

Three years (2006–08) of UK household survey data were used. The Expenditure and Food Survey provides comprehensive 2-week data on household expenditure. Regression analyses were used to investigate the relationships between the purchase of cheap off-trade alcohol, household income levels and whether the household level of alcohol purchasing is categorized as moderate, hazardous or harmful, while controlling for other household and non-household characteristics. Predicted probabilities and quantities for cheap alcohol purchasing patterns were generated for all households.

Results

The descriptive statistics and regression analyses indicate that low-income households are not the predominant purchasers of any alcohol or even of cheap alcohol. Of those who do purchase off-trade alcohol, the lowest income households are the most likely to purchase cheap alcohol. However, when combined with the fact that the lowest income households are the least likely to purchase any off-trade alcohol, they have the lowest probability of purchasing cheap off-trade alcohol at the population level. Moderate purchasing households in all income quintiles are the group predicted as least likely to purchase cheap alcohol. The predicted average quantity of low-cost off-trade alcohol reveals similar patterns.

Conclusion

The results suggest that heavier household purchasers of alcohol are most likely to be affected by the introduction of a ‘minimum price per unit of alcohol’ policy. When we focus only on those households that purchase off-trade alcohol, lower income households are the most likely to be affected. However, minimum pricing in the UK is unlikely to be significantly regressive when the effects are considered for the whole population, including those households that do not purchase any off-trade alcohol. Minimum pricing will affect the minority of low-income households that purchase off-trade alcohol and, within this group, those most likely to be affected are households purchasing at a harmful level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

1 Off-trade alcohol refers to purchases from retail establishments for consumption off premises.

2 An enquiry into the UK grocery market found that alcohol was one of two product groups for which below-cost selling was most prevalent.[8]

3 A unit is 10 mL of pure alcohol.

4 These results are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 2009; 373(9682): 2234–46

WHO. Evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce alcohol related harm. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/disease-prevention/alcohol-use/publications/2009/evidence-for-the-effectiveness-and-costeffectiveness-of-interventions-to-reduce-alcohol-related-harm [Accessed 2010 Mar 4]

Chisholm D, Rehm J, van Ommeren M, et al. Reducing the global burden of hazardous alcohol use: a comparative cost effectiveness analysis. J Stud Alcohol 2004; 65: 782–93

Booth A, Meier P, Stockwell T, et al. Independent review of the effects of alcohol pricing and promotion. Part A. Systematic reviews. London: Department of Health, 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthimprovement/Alcoholmisuse/DH_085390 [Accessed 2009 Mar 3]

Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction 2009; 104:179–10

Elder RW, Lawrence B, Ferguson A, et al. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med 2010; 38(2): 217–29

Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2010; 100(11): 2270–8

Competition Commission The supply of groceries in the UK: market investigation. London: Competition Commission [online]. Available from URL: http://www.competition-commission.org.uk/rep_pub/reports/2008/538grocery.htm [Accessed 2011 Jul 11]

Byrnes JM, Cobiac LJ, Doran CM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of volumetric alcohol taxation in Australia. Med J Australia 2010; 192(8): 439–44

Chaloupka FJ, Grossman M, Saffer H. The effects of price on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Res Health 2002; 26: 22–34

Young DJ, Bielinska-Kwapisz A. Alcohol consumption, beverage prices and measurement error. J Stud Alcohol 2003; 64(2): 235–8

Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, Holder HD, et al. Alcohol prices, beverage quality, and the demand for alcohol: quality substitutions and price elasticities. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res 2006; 30(1): 96–105

Purshouse RC, Meier PS, Brennan A, et al. Estimated effect of alcohol pricing policies on health and health economic outcomes in England: an epidemiological model. Lancet 2010; 375: 1355–64

Scottish Parliament. Health and Sport Committee Official Report, 10 February 2010 [online]. Available from URL: http://archive.scottish.parliament.uk/s3/committees/hs/or-10/he10-0502.htm#Col2694 [Accessed 2011 Oct 28]

Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Who drinks most of the alcohol in the US? The policy implications. J Stud Alcohol 1999; 60(1): 78–89

Scottish Government. Minimum alcohol price named [news release]. Available from URL: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2010/09/02102755 [Accessed 2011 Aug 4]

The Nielsen Company. Alcohol sales dataset 2005-2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/alcoholSalesDataset2005-2009-20100720.xls [Accessed 2011 Feb 8]

Department of Health. Units and you, 2008 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_085427.pdf [Accessed 2010 Mar 14]

Rafferty A. Introductory guide to the Expenditure and Food Survey. ESDS Government 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.esds.ac.uk/government/docs/efsguide.pdf [Accessed 2009 Jul 10]

Office for National Statistics and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Expenditure and Food Survey, 2006. 3rd edition. Colchester: UK Data Archive July 2009. SN: 5986 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.esds.ac.uk/government/efs/ [Accessed 2010 Feb 1]

Office for National Statistics and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Expenditure and Food Survey, 2007. Colchester: UK Data Archive, February 2009. SN: 6118 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.esds.ac.uk/government/efs/ [Accessed 2010 Mar 12]

Office for National Statistics and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Living Costs and Food Survey, 2008. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive, March 2010. SN: 6385[online]. Available from URL: http://www.esds.ac.uk/government/efs/ [Accessed 2010 May 16]

Information Services Division. Alcohol Statistics Scotland 2009. Edinburgh: Common Services Agency, 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.alcoholinformation.isdscotland.org/alcohol_misuse/controller?p_service=Content.show&p_applic=CCC&pContentID=1407 [Accessed 2009 12 May]

Mäkelä P, Paljärvi T. Do consequences of a given pattern of drinking vary by socioeconomic status? A mortality and hospitalisation follow-up for alcohol-related causes of the Finnish Drinking Habits Surveys. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008; 62: 728–33

Huckle T, Quan R, Casswell S. Socio-economic status predicts drinking patterns but not alcohol-related consequences independently. Addiction 2010; 105: 1192–202

Herttua K, Mäkelä P, Martikainen P. Changes in alcohol-related mortality and its socioeconomic differences after a large reduction in alcohol prices: a natural experiment based on register data. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168(10): 1110–8

Hunt P, Rabinovich L, Baumberg B. Preliminary assessment of the economic impacts of alcohol pricing policy options in the UK. London: Home Office. 2010 [online] Available from URL: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/alcohol-drugs/alcohol/alcohol-pricing/?view=Standard&pubID=851393 [Accessed 2011 Oct 28]

Mahajan S. Concentration ratios for business by industry in 2004. Econ Trends 2006; 635:25–47

Keeler TE, Hu T-W, Barnett PG, et al. Do cigarette producers discriminate by state? An empirical analysis of local cigarette pricing and taxation. J Health Econ 1996; 15: 499–512

Kunreuther H. Why the poor may pay more for food: theoretical and empirical evidence. J Bus 1973; 46(3): 368–83

Brennan A, Purhouse R, Taylor K. Independent review of the effects of alcohol pricing and promotion. Part B. London: Department of Health, 2008. Available from URL: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthimprovement/Alcoholmisuse/DH_085390 [Accessed 2009 Mar 3]

Longford NT, Ely M, Hardy R, et al. Handling missing data in diaries of alcohol consumption. J Royal Stat Soc A 2000; 163(3): 381–402

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Office for National Statistics and Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Expenditure and Food Survey, Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive for access to data from EFS survey years 2006, 2007 and 2008.

Neither the original data creators, depositors or copyright holders, the funders of the Data Collections, nor the UK Data Archive bear any responsibility for the accuracy or comprehensiveness of these materials.

Funding to the Health Economics Research Unit from the Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are responsible for all views expressed and these should not be attributed to any funding body. The authors would like to thank anonymous referees for their comments and the resulting improvements in the paper.

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ludbrook, A., Petrie, D., McKenzie, L. et al. Tackling alcohol misuse. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 10, 51–63 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2165/11594840-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11594840-000000000-00000