-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jens Søndergaard, Dorte Gilså Hansen, Peter Aarslev, Anders P Munck, A multifaceted intervention according to the Audit Project Odense method improved secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease: a randomised controlled trial, Family Practice, Volume 23, Issue 2, April 2006, Pages 198–202, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmi090

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background. No single quality improvement instrument has proved consistently effective, but multifaceted interventions are believed to have the greatest impact. However, only little is known regarding what combinations are likely to be successful.

Objective. To evaluate the impact of a multifaceted intervention strategy combining GP registrations, outreach visits and feedback, targeting secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease in general practice.

Methods. A randomised controlled trial including 28 GPs in Ringkjøbing County, Denmark. Half of the GPs received outreach visits and feedback on their prescribing of heart disease drugs. Evaluation was based on registration of consultations with patients suffering from ischemic heart disease.

Results. The intervention had a statistically significant impact on prescribing of lipid lowering drugs [odds ratio 1.59; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00 to 2.53] and acetylsalicylic acid (odds ratio 2.54; 95% CI 1.21 to 5.31).

Conclusion. An intervention strategy combining outreach visits, feedback and GP registrations is a promising way of improving the quality of preventive treatment in general practice.

Søndergaard J, Hansen DG, Aarslev P and Munck AP. A multifaceted intervention according to the Audit Project Odense method improved secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease: a randomised controlled trial. Family Practice 2006; 23: 198–202.

Introduction

The last few decades have seen an increasing focus on the need to implement new evidence in general practice. Various kinds of interventions have been undertaken, but achieving improvements in practice patterns is not an easy task and there have been many failures.1,2 Dissemination of knowledge in the form of written information or courses alone has not proved effective, whereas strategies more actively involving the participants, e.g. outreach visits and feedback, often have some impact.3–6

However, no single intervention has proved consistently effective. Most changes in GP behaviour are probably a result of various kinds of influence, and further studies have to be done to determine what combination of interventions is likely to be most effective. The Audit Project Odense (APO) method is an increasingly popular quality improvement concept including GPs' repeated registrations of their own activities, feedback, additional interventions and a final evaluation.7 Many APO quality improvement interventions have been undertaken and most appear to have had a positive effect.7 Due to the design of the evaluations, however, the evidence supporting an effect of the APO method is insufficient and there is a need for more rigorous evaluations.7

Ischemic heart disease is very frequent in the Western world. In order to reduce morbidity and mortality, it is necessary to offer appropriate secondary preventive treatment, e.g. cholesterol lowering therapy, acetylsalicylic acid, smoking cessation, diet and exercise.8,9 Information and clinical guidelines on the topic have been distributed to all Danish GPs,9 but still many patients do not receive the recommended treatment.10 In cooperation with APO, a group of GPs therefore planned a quality improvement project including registration by the participants, outreach visits and feedback.

The objective of this paper was to evaluate, in a randomised controlled design, the impact of a multifaceted intervention strategy combining GP registrations, outreach visits and feedback, targeting secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease in general practice.

Methods

Study population

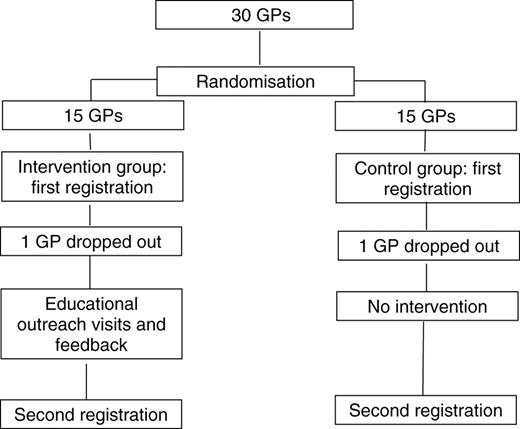

All 186 GPs in Ringkjøbing County, Denmark were invited by the local quality improvement committee for general practice to participate in the study. The 30 GPs who accepted to participate were randomly allocated to an intervention group (15) and a control group (15). Subsequently, one from each group dropped out (Fig. 1). Allocation was done using a computer programme based on a random number sequence.

GP registrations

During six weeks in the year 2000, both groups registered all surgery consultations where the reason for encounter was related to ischemic heart disease (baseline performance data). Two years later, both groups repeated those registrations. The registrations were made on a simple APO registration form, and each patient was registered only once during a 6-week period. The data included information on each patient's age and sex, weight and height, type of heart disease, risk factors (e.g. smoking and diabetes), blood pressure, cholesterol values, preventive actions taken and treatment with cardiovascular drugs including lipid lowering drugs and acetylsalicylic acid.

Intervention

The intervention group GPs each received two educational outreach visits by two GPs with good communication skills and profound insight into ischemic heart disease. Risk reduction measures and other themes related to secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease were discussed. In order to enhance the educational process, the GPs were requested to identify two or three case stories in advance. Furthermore, each outreach visit included the following educational material:

Feedback forms showing the GP's performance data based on the initial registration.

Two guideline summaries on prevention of ischemic heart disease9 and motivational interviewing.11

Information about risk reduction measures.

A price list of cardiovascular drugs.

Patient handouts with advice on smoking cessation, diet and exercise.

Three case stories focusing on different aspects of ischemic heart disease.

Feedback information on the GP's prescribing of reimbursed heart disease drugs. For comparison, these data were presented together with data for other GPs in the county.

Each educational visit was made according to a checklist to ensure that all the above topics were discussed.

Process measures of ischemic heart disease treatment

The aim of the intervention was primarily to increase the proportion of patients being treated with lipid-lowering drugs and acetylsalicylic acid (primary outcome measure) and secondarily to increase the frequency of cholesterol measuring and counselling on exercise, smoking cessation and diet (secondary outcome measures).

Data analyses

The association between intervention and changes in outcome variables was assessed using logistic regression analyses. We adjusted for clustering at the level of the individual GP, thus accounting for non-independence of observations within each practice.12 Results are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Pre-study power calculations based on a previous APO study indicated that a trial with 25 GPs in each group had a power of 80% to detect a 10% increase in the rate of appropriate medication with lipid lowering drugs. Analyses were performed using the statistical software STATA 8.0.13

Results

A total of 28 GPs participated in both registrations. The GPs registered 314 patients during the first registration period (193 in the intervention and 122 in the control group) and 319 during the second period (157 in the intervention and 162 in the control group). Male patients accounted for 52.5% (379) of the consultations. Table 1 shows the distribution of diagnostic categories.

Diagnoses of heart disease in patients included in intervention and control groups in the years 2000 and 2002

| Diagnoses . | Intervention group . | . | Control group . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | ||

| Myocardial infarction less than 2 years old | 27 (14%) | 29 (18%) | 11 (9%) | 24 (15%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction more than 2 years old | 53 (27%) | 73 (47%) | 32 (26%) | 39 (24%) | ||

| Angina pectoris | 65 (34%) | 36 (23%) | 42 (35%) | 58 (36%) | ||

| Other heart disease | 35 (18%) | 19 (12%) | 30 (25%) | 40 (25%) | ||

| More than one diagnosis | 11 (6%) | 0 (%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| No diagnosis | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Total | 193 (100%) | 157 (100%) | 122 (100%) | 163 (100%) | ||

| Diagnoses . | Intervention group . | . | Control group . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | ||

| Myocardial infarction less than 2 years old | 27 (14%) | 29 (18%) | 11 (9%) | 24 (15%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction more than 2 years old | 53 (27%) | 73 (47%) | 32 (26%) | 39 (24%) | ||

| Angina pectoris | 65 (34%) | 36 (23%) | 42 (35%) | 58 (36%) | ||

| Other heart disease | 35 (18%) | 19 (12%) | 30 (25%) | 40 (25%) | ||

| More than one diagnosis | 11 (6%) | 0 (%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| No diagnosis | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Total | 193 (100%) | 157 (100%) | 122 (100%) | 163 (100%) | ||

Diagnoses of heart disease in patients included in intervention and control groups in the years 2000 and 2002

| Diagnoses . | Intervention group . | . | Control group . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | ||

| Myocardial infarction less than 2 years old | 27 (14%) | 29 (18%) | 11 (9%) | 24 (15%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction more than 2 years old | 53 (27%) | 73 (47%) | 32 (26%) | 39 (24%) | ||

| Angina pectoris | 65 (34%) | 36 (23%) | 42 (35%) | 58 (36%) | ||

| Other heart disease | 35 (18%) | 19 (12%) | 30 (25%) | 40 (25%) | ||

| More than one diagnosis | 11 (6%) | 0 (%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| No diagnosis | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Total | 193 (100%) | 157 (100%) | 122 (100%) | 163 (100%) | ||

| Diagnoses . | Intervention group . | . | Control group . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | ||

| Myocardial infarction less than 2 years old | 27 (14%) | 29 (18%) | 11 (9%) | 24 (15%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction more than 2 years old | 53 (27%) | 73 (47%) | 32 (26%) | 39 (24%) | ||

| Angina pectoris | 65 (34%) | 36 (23%) | 42 (35%) | 58 (36%) | ||

| Other heart disease | 35 (18%) | 19 (12%) | 30 (25%) | 40 (25%) | ||

| More than one diagnosis | 11 (6%) | 0 (%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| No diagnosis | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Total | 193 (100%) | 157 (100%) | 122 (100%) | 163 (100%) | ||

Table 2 shows that the intervention had a statistically significant impact on treatment with lipid lowering drugs [odds ratio (OR) 1.59; 95% CI 1.00 to 2.53] and acetylsalicylic acid (OR 2.54; 95% CI 1.21 to 5.31) (primary outcome measures). The intervention did not have a statistically significant impact on serum cholesterol measuring (OR 2.29; 95% CI 0.98 to 5.33), advice on exercise (OR 2.22; 95% CI 0.81 to 6.07), smoking cessation (OR 1.40; 95% CI 0.64 to 3.64) and diet (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.50 to 2.69) (secondary outcome measures). An aggregate analysis examining whether there was an impact on one or more of the four secondary outcomes showed a statistically significant odds ratio (OR 3.06; 95% CI 1.15 to 8.07).

Intervention effects

| Outcome . | Intervention group Frequency % (n) . | . | Control group Frequency % (n) . | . | Odds ratio for an intervention effect . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | OR (95% CI) . | |||||

| Primary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid | 78% (151) | 92% (145) | 77% (93) | 81% (132) | 2.54 (1.21;5.31) | |||||

| Treatment with lipid lowering drugs | 30% (58) | 55% (86) | 31% (37) | 44% (71) | 1.59 (1.00;2.53) | |||||

| Secondary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Measuring total cholesterol | 66% (128) | 85% (134) | 69% (84) | 74% (120) | 2.29 (0.98;5.33) | |||||

| Advice on exercise | 14% (27) | 28% (44) | 20% (24) | 21% (34) | 2.22 (0.81;6.07) | |||||

| Advice on diet | 41% (79) | 45% (70) | 37% (45) | 37% (60) | 1.15 (0.50;2.69) | |||||

| Advice on smoking cessation | 10% (20) | 15% (24) | 11% (13) | 12% (19) | 1.40 (0.54;3.64) | |||||

| Outcome . | Intervention group Frequency % (n) . | . | Control group Frequency % (n) . | . | Odds ratio for an intervention effect . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | OR (95% CI) . | |||||

| Primary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid | 78% (151) | 92% (145) | 77% (93) | 81% (132) | 2.54 (1.21;5.31) | |||||

| Treatment with lipid lowering drugs | 30% (58) | 55% (86) | 31% (37) | 44% (71) | 1.59 (1.00;2.53) | |||||

| Secondary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Measuring total cholesterol | 66% (128) | 85% (134) | 69% (84) | 74% (120) | 2.29 (0.98;5.33) | |||||

| Advice on exercise | 14% (27) | 28% (44) | 20% (24) | 21% (34) | 2.22 (0.81;6.07) | |||||

| Advice on diet | 41% (79) | 45% (70) | 37% (45) | 37% (60) | 1.15 (0.50;2.69) | |||||

| Advice on smoking cessation | 10% (20) | 15% (24) | 11% (13) | 12% (19) | 1.40 (0.54;3.64) | |||||

Intervention effects

| Outcome . | Intervention group Frequency % (n) . | . | Control group Frequency % (n) . | . | Odds ratio for an intervention effect . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | OR (95% CI) . | |||||

| Primary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid | 78% (151) | 92% (145) | 77% (93) | 81% (132) | 2.54 (1.21;5.31) | |||||

| Treatment with lipid lowering drugs | 30% (58) | 55% (86) | 31% (37) | 44% (71) | 1.59 (1.00;2.53) | |||||

| Secondary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Measuring total cholesterol | 66% (128) | 85% (134) | 69% (84) | 74% (120) | 2.29 (0.98;5.33) | |||||

| Advice on exercise | 14% (27) | 28% (44) | 20% (24) | 21% (34) | 2.22 (0.81;6.07) | |||||

| Advice on diet | 41% (79) | 45% (70) | 37% (45) | 37% (60) | 1.15 (0.50;2.69) | |||||

| Advice on smoking cessation | 10% (20) | 15% (24) | 11% (13) | 12% (19) | 1.40 (0.54;3.64) | |||||

| Outcome . | Intervention group Frequency % (n) . | . | Control group Frequency % (n) . | . | Odds ratio for an intervention effect . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 2000 . | 2002 . | 2000 . | 2002 . | OR (95% CI) . | |||||

| Primary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid | 78% (151) | 92% (145) | 77% (93) | 81% (132) | 2.54 (1.21;5.31) | |||||

| Treatment with lipid lowering drugs | 30% (58) | 55% (86) | 31% (37) | 44% (71) | 1.59 (1.00;2.53) | |||||

| Secondary outcomes: | ||||||||||

| Measuring total cholesterol | 66% (128) | 85% (134) | 69% (84) | 74% (120) | 2.29 (0.98;5.33) | |||||

| Advice on exercise | 14% (27) | 28% (44) | 20% (24) | 21% (34) | 2.22 (0.81;6.07) | |||||

| Advice on diet | 41% (79) | 45% (70) | 37% (45) | 37% (60) | 1.15 (0.50;2.69) | |||||

| Advice on smoking cessation | 10% (20) | 15% (24) | 11% (13) | 12% (19) | 1.40 (0.54;3.64) | |||||

Discussion

In comparison with the control group GPs, intervention group GPs became more likely to prescribe lipid lowering drugs and acetylsalicylic acid. This multifaceted APO design combining GP registrations with outreach visits and feedback thus seems to be a promising method to improve GPs' secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease.

However, a number of factors must be considered. First, the very fact that the GPs had to register their consultations and consequently their treatment could, in theory, have exaggerated the quality of the care given.14 But in this study both the intervention and control group GPs conducted such registrations and therefore both groups could, in theory, have overestimated their actual performance. The consequence would be less room for improvement which, in turn, could lead to an underestimation of the effects.

Second, there are minor differences between the patterns of diagnosis in the two groups. During the second period, a larger proportion of patients in the intervention than in the control group suffered from old myocardial infarctions (MI). The motivation for change of therapy among patients with a recent MI is likely to be higher than among patients with an older MI. Hence, the effect of the higher number of old MIs in the intervention group is likely to lead to an underestimation of the impact of the intervention. Third, the wide confidence intervals for some of the outcomes indicate that we had too little statistical power to detect effects for all outcomes. However, the intervention turned out to be so powerful that the impact was actually statistically significant for the primary outcomes. Although no statistically significant effect was observed on the individual secondary outcomes, the analyses examining whether one or more of these outcomes had been achieved showed a statistically significant effect. Further, taking the point estimates into consideration, it is likely that a larger study would find positive effects for all outcomes. Fourthly, several studies have shown that treatment with lipid lowering drugs15 and acetylsalicylic acid16 as well as advice on exercise,16 diet16 and smoking cessation16 are important components of secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease in terms of reduced morbidity and mortality, but there may also be other important outcome measures.16 Fifthly, a key question is whether the results are generalisable to other types of disease and other groups of GPs. In the past years, APO quality improvement programmes have been disseminated to a number of countries, including Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland and Spain. In all these countries, the participating GPs have welcomed the concept. As APO programmes are always designed specifically for voluntary participation, we cannot predict whether the concept will work by compulsory participation. Based on its success in non-randomised studies, we have no reason to believe that the APO concept is less effective among other groups of voluntarily participating GPs in Denmark or other countries or when addressing other topics, but obviously the question of generalisability should be addressed by conducting more randomised controlled studies.

Why did this multifaceted intervention have an impact? Changes in clinical practice are achieved through an interaction between motivation, competence and barriers and should be based on professional behavioural theories.17 The APO concept is based on adult learning theories. Since learning, not teaching, makes doctors change their practice, the interventions should be aimed at facilitating change in clinical practice.18,19 Single interventions only rarely improve physicians' performance whereas combined strategies seem more effective.2,20 Voluntary participation is the cornerstone of all APOs—it seems to give the GPs a sense of ownership of the intervention, which is essential to impact.21,22 Further, unsolicited interventions may be perceived as a threat to clinical freedom and thus make change unlikely.23,24 The registrations are a simple and practical way of giving the physicians insight into their own practice, which is a prerequisite for motivating them to change their behaviour.19,23,25 We delivered our core messages by letting specially trained GPs visit the participants in their consultations. The rationale behind this was that outreach visits in themselves have proved to be one of the most effective ways to influence physicians, and that this effect may be strengthened by visits from peers with a profound insight into general practice.26 Future studies should compare different types of complex interventions, taking into account aspects like costs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a multifaceted intervention combining GP registration of their treatment, outreach visits and feedback is a promising way of improving the quality of preventive care in general practice.

Declaration

Funding: the Quality Assurance Committee for General Practice in Ringkjøbing County and The Danish National Research Foundation for Primary Care.

Ethical approval: this study did not need approval by an ethical committee.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Henrik Støvring is thanked for statistical assistance, Ole May, Bent Egebjerg, Torben Nielsen and Birgit Toft are thanked for participating in the planning and realisation the intervention.

References

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group.

Wensing M, Grol R. Single and Combined Strategies for Implementing Changes in Primary Care: A literature Review.

Granados A, Jonsson E, Banta HD, Bero L, Bonair A, Cochet C et al. EUR-ASSESS Project Subgroup Report on Dissemination and Impact.

Freemantle N, Harvey E, Grimshaw J, Grilli R, Bero LA. Printed educational materials to improve the behavior of health care professionals and patient outcomes.

Thomson O'Brien MA, Oxman AD, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Freemantle N, Harvey EL. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Thomson O'Brien MA, Oxman AD, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Freemantle N, Harvey EL. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes.

Munck A, Damsgaard JJ, Hansen DG, Bjerrum L, Søndergaard J. The Nordic method for quality improvement in general practice.

Smith SC Jr, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Cerqueira MD, Dracup K et al. AHA/ACC Scientific Statement: AHA/ACC guidelines for preventing heart attack and death in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: 2001 update: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

Christensen B, Heebøll-Nielsen NC, Madsen LD, Lous J, Færgemann O, Steender S. Prevention of ischaemic heart disease in general practice. Copenhagen: Danish College of General Practitioners;

Larsen J, Andersen M, Bjerrum L, Kragstrup J, Gram L. Insufficient use of lipid-lowering drugs and measurement of serum cholesterol among patients with a history of myocardial infarction.

Mabeck CE, Kallerup H, Maunsbach M. Motivational interviewing. Copenhagen, Danish College of General Practitioners;

Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. London: Arnold;

Adams A, Soumerai S, Lomas J, Ross-Degnan D. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines.

Pedersen T, Wilhelmsen L, Faergeman O, Strandberg T, Thorgeirsson G, Troedsson L et al. Follow-up study of patients randomized in the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S) of cholesterol lowering.

De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, Brotons C, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third Joint Task Force of European and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice.

Fox RD, Mazmanian PE, Putnam RW. Changing and learning in the lives of physicians. New York: Praeger;

Fox RD, Bennett NL. Learning and change: implications for continuing medical education.

Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice.

Lomas J. Teaching old (and not so old) docs new tricks: effective ways to implement research findings. In Dunn EV, Norton PG, Stewart M, Tudiver F, Bass MJ (eds). Disseminating research/changing practice. Research methods for primary care. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;

Søndergaard J, Andersen M, Kragstrup J, Hansen HP, Gram LF. Why has prescriber feedback no substantial impact on General Practitioners' prescribing practice? A qualitative study.

Robertson N, Baker R, Hearnshaw H. Changing the clinical behaviour of doctors: a psychological framework.

Munck AP, Gahrn-Hansen B, Sogaard P, Sogaard J. Long-lasting improvement in general practitioners' prescribing of antibiotics by means of medical audit.

Author notes

aResearch Unit for General Practice, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, bResearch Unit for General Practice, University of Aarhus and cGeneral Practice, Herning, Denmark.

Comments

Dear Professor Delaney,

We read with interest the paper by Sondergaard et al. (1) on the achievement of improved secondary prevention of heart disease in Denmark using a multi-faceted intervention. We are currently carrying out a randomised controlled trial in Irish general practice of another complex intervention, also designed to improve secondary prevention of heart disease (the SPHERE study) (2).

The Danish intervention significantly increased prescribing of lipid- lowering drugs and aspirin. While this outcome is to be welcomed, we feel the authors are being over-optimistic in concluding that the Audit Project Odense is ‘a promising way of improving the quality of preventive treatment’. The key area for research in this field is not improving prescribing but achieving long-term lifestyle behaviour change (3). This approach is supported by a recently-published paper on the World Health Organization’s MONICA project which acknowledges that medication alone could not have been responsible for patterns of declining blood pressure across Europe and highlights that ‘other factors, potentially of great public health interest, were more pervasive and powerful’ such as ‘lifestyle or hygienic methods of controlling risk factors’ (4).

The multi-faceted approach of the SPHERE intervention targets both medication prescribing and behaviour change (5), in a bid to tackle the determinants of heart disease as comprehensively as possible. Final results of this trial will be published in 2008 when we hope to be able to shed further light on effective solutions to this important public health issue.

Finally, a detailed protocol describing the various components of a complex intervention, together with parallel qualitative work, can be helpful in delineating the relative effectiveness of different elements.

Yours sincerely,

Dr. Mary C Byrne, Department of General Practice, NUI, Galway

Dr. Margaret C Cupples, Department of General Practice, Queen’s University Belfast

Dr. Susan M Smith, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Trinity College Dublin

Dr. Molly Byrne, Department of Psychology, NUI, Galway

Prof. Andrew W Murphy, Department of General Practice, NUI, Galway

References

1. Sondergaard J, Hansen DG, Aarslev P, Munck AP. A multifaceted intervention according to the Audit Project Odense method improved secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease: a randomised controlled trial. Fam. Pract. 2006;23(2):198-202.

2. Murphy AW, Cupples ME, Smith S, Byrne M, Leathem C, Byrne MC. The SPHERE Study. Secondary prevention of heart disease in general practice: protocol of a randomised controlled trial of tailored practice and patient care plans with parallel qualitative, economic and policy analyses. [ISRCTN24081411]. Current Controlled Trials in Cardiovascular Medicine 2005. Jul 29;6(1):11

3. Hulscher MEJL, Wensing M, van der Weijden T, Grol R. Interventions to implement prevention in primary care. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000362. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000362.pub2.

4. Tunstall-Pedoe H, Connaghan J, Woodward M, Tolonen H, Kuulasmaa K. Pattern of declining blood pressure across replicate population surveys of the WHO MONICA project, mid-1980s to mid-1990s, and the role of medication. BMJ, doi:10.1136/ bmj.38753.779005.BE (published 10 March 2006).

5. Byrne M, Corrigan M, Cupples ME, Smith SM, Leathem C, Murphy AW. The SPHERE study: Using psychological theory to inform the development of behaviour change training for primary care staff to increase secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Irish Journal of Psychology 2005; 26(1-2):53-64.

Conflict of Interest:

None declared