Abstract

This study aims to identify the extent of terminal digit bias in routinely recorded blood pressures (BP) across a number of different general practices and report on changes in terminal digit bias over a 10-year period. It also explores the effect this may have had on the mean recorded BP in this population. BP records were taken from The Health Improvement Network database containing anonymized patient records from information entered by UK general practices in the financial years 1996–1997 to 2005–2006. The proportion of measurements ending in zero and the mean BP readings were calculated for each practice and for each year of data.

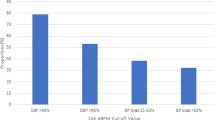

Over this 10-year period the percentage of systolic BPs with zero terminal digits fell from 71.2 to 36.7% and mean recorded BP fell from 152.3 to 145.3 mm Hg. Correcting the BPs to remove terminal digit bias indicates a 2–3 mm Hg underestimation of the mean population systolic BP over this period. The between-practice variation in the percentage of zero terminal digit readings increased from 3.5 to 6.5 s.d. Although it is welcome to see a reduction in terminal digit bias, it is worrying to see the increase in variation between practices. There is evidence that terminal digit bias may lead to potential misclassification and inappropriate treatment of hypertensive patients. The increase in variation observed may therefore lead to an increased variation in the quality of care given to patients.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: partial update. Royal College of Physicians: London 2006.

Quality and Outcomes Framework, 2004/05. The Information Centre for Health and Social Care 2006, Available from: URL: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/services/qof/data/.

Matthys J, De Meyere M, Mervielde I, Knottnerus JA, Den Hond E, Staessen JA et al. Influence of the presence of doctors-in-training on the blood pressure of patients: a randomised controlled trial in 22 teaching practices.(see comment). J Hum Hypertens 2004; 18 (11): 769–773.

Marshall T, Anantharachagan A, Choudhary K, Chue C, Kaur I . A randomised controlled trial of the effect of anticipation of a blood test on blood pressure. J Hum Hypertens 2002; 16 (9): 621–625.

Bakx JC, Netea RT, van den Hoogen HJM, Oerlemans G, van Dijk R, van den Bosch WJHM et al. De invloed van een rustperiode op de bloeddruk. {The influence of a rest period on blood pressure measurement}. Huisarts en Wetenschap 1999; 42: 53–56.

Bakx C, Oerlemans G, van den Hoogen H, van Weel C, Thien T . The influence of cuff size on blood pressure measurement. J Hum Hypertens 1997; 11 (7): 439–445.

Reeves RA . The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have hypertension? How to measure blood pressure (see comment). (Review). JAMA 1995; 273 (15): 1211–1218.

Rouse A, Marshall T . The extent and implications of sphygmomanometer calibration error in primary care. J Hum Hypertens 2001; 15 (9): 587–591.

Ali S, Rouse A . Practice audits: reliability of sphygmomanometers and blood pressure recording bias. J Hum Hypertens 2002; 16 (5): 359–361.

Nietert PJ, Wessell AM, Feifer C, Ornstein SM . Effect of terminal digit preference on blood pressure measurement and treatment in primary care. Am J Hypertens 2006; 19 (2): 147–152.

Patterson HR . Sources of error in recording the blood pressure of patients with hypertension in general practice. BMJ 1984; 289 (6459): 1661–1664.

Wingfield D, Freeman GK, Bulpitt CJ, General Practice Hypertension Study Group (GPHSG). Selective recording in blood pressure readings may increase subsequent mortality. QJM 2002; 95 (9): 571–577.

Wingfield D, Cooke J, Thijs L, Staessen JA, Fletcher AE, Fagard R et al. Terminal digit preference and single-number preference in the Syst-Eur trial: influence of quality control. Blood Press Monit 2002; 7 (3): 169–177.

Wen SW, Kramer MS, Hoey J, Hanley JA, Usher RH . Terminal digit preference, random error, and bias in routine clinical measurement of blood pressure. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46 (10): 1187–1193.

Thavarajah S, White WB, Mansoor GA . Terminal digit bias in a specialty hypertension faculty practice. J Hum Hypertens 2003; 17 (12): 819–822.

Graves JW, Bailey KR, Grossardt BR, Gullerud RE, Meverden RA, Grill DE et al. The impact of observer and patient factors on the occurrence of digit preference for zero in blood pressure measurement in a hypertension specialty clinic: evidence for the need of continued observation. Am J Hypertens 2006; 19 (6): 567–572.

Nuutinen M, Turtinen J, Uhari M . Random-zero sphygmomanometer, Rose's tape, and the accuracy of the blood pressure measurements in children. Pediatr Res 1992; 32 (2): 243–247.

McManus RJ, Mant J, Hull MR, Hobbs FD . Does changing from mercury to electronic blood pressure measurement influence recorded blood pressure? An observational study.(see comment). Br J Gen Pract 2003; 53 (497): 953–956.

Stoneking HT, Hla KM, Samsa GP, Feussner JR . Blood pressure measurements in the nursing home: are they accurate? Gerontologist 1992; 32 (4): 536–540.

Hessel PA . Terminal digit preference in blood pressure measurements: effects on epidemiological associations. Int J Epidemiol 1986; 15 (1): 122–125.

Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, Jordan RE . Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ 2003; 326 (7404): 1427.

Ramsay L, Williams B, Johnston G, MacGregor G, Poston L, Potter J et al. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the third working party of the British Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens 1999; 13 (9): 569–592.

National Centre for Social Research. Health survey for England 2003. Department of Health: London 2005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harrison, W., Lancashire, R. & Marshall, T. Variation in recorded blood pressure terminal digit bias in general practice. J Hum Hypertens 22, 163–167 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1002312

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1002312

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Blood pressure recording bias during a period when the Quality and Outcomes Framework was introduced

Journal of Human Hypertension (2009)