Abstract

In recent years, there have been significant advances in the clinical management of patients with wet age-related macular degeneration (wet AMD)—a rapidly progressing and potentially blinding degenerative eye disease. Wet AMD is responsible for more than half of registered severe sight impairment (blindness) in the United Kingdom, and patients who are being treated for wet AMD require frequent and long-term follow-up for treatment to be most effective. The clinical workload associated with the frequent follow-up required is substantial. Furthermore, as more new patients are diagnosed and the population continues to age, the patient population will continue to increase. It is thus vital that clinical services continue to adapt so that they can provide a fast and efficient service for patients with wet AMD. This Action on AMDdocument has been developed by eye health-care professionals and patient representatives, the Action on AMDgroup. It is intended to highlight the urgent and continuing need for change within wet AMD services. This document also serves as a guide for eye health-care professionals, NHS commissioners, and providers to present possible solutions for improving NHS retinal and macular services. Examples of good practice and service development are considered and can be drawn upon to help services meet the recommended quality of care and achieve best possible outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neovascular wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a serious macular disorder resulting in progressive loss of central vision. In the United Kingdom, wet AMD accounts for more than half of all cases of registered severe sight impairment (blindness) and sight impairment.1, 2 There are ∼26 000 new cases of wet AMD each year in the United Kingdom.3 The prevalence of wet AMD is continuing to increase with the ageing population.4 Significant vision can be lost in a short time if wet AMD is not adequately treated,5 and this can have a huge impact on independence and quality of life for patients.6

Until 3 years ago, the only available licensed and NICE-approved treatment option for wet AMD was verteporfin photodynamic therapy (vPDT), which was only suitable for a small proportion of eyes.7 Patients with minimally classic and occult lesions, which account for 55–70% of all patients with wet AMD, were not eligible for treatment with vPDT.8 Significant advances have been made in recent years with the advent of intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment that is effective in patients with wet AMD of any lesion type.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)-recommended treatment for wet AMD is currently ranibizumab (Lucentis®▾), an anti-VEGF drug that has shown superiority to vPDT.9 The Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) approved ranibizumab before NICE and, subsequently, NHS Quality Improvement Scotland has advised that NICE recommendations are valid for Scotland as well. The SMC also approved pegaptanib (Macugen®), another licensed anti-VEGF treatment as an alternative, although this is not widely used. Ranibizumab has proven efficacy in preventing visual loss in patients with wet AMD and can also significantly improve vision in more than one-third of patients, with generally good tolerability.9, 10, 11 The improvement in visual acuity (VA) seen with this treatment also translates into improved patient-reported benefits in quality of life (near activities, distance activities, and activity of daily living tasks).12, 13, 14

The guidance from NICE (in 2008) and the SMC (in 2007) recommending intravitreal ranibizumab treatment for all wet AMD patients, irrespective of lesion type, meant that the number of patients potentially suitable for treatment rose markedly. Furthermore, the number of clinic visits required for each patient increased because patients receiving ranibizumab require monthly follow-up (compared with every 3 months following vPDT). Many local wet AMD services in the NHS adapted to meet these increases in demand, and there have also been substantial improvements in rapid referral and fast-track processes for new patients.

Despite these initial improvements and service adaptations, limited or inadequate clinical capacity continues to threaten optimal care and access to potentially sight-saving treatment for wet AMD patients. Some NHS clinics are failing to maintain recommended follow-up intervals for patients with wet AMD. Delay in follow-up beyond the recommended interval may cause patients to unnecessarily lose vision permanently. This is important because sight impairment and severe sight impairment are associated with costs in the United Kingdom health-care system, totalling £22 billion in 2008.15 These costs include £2.14 billion direct costs (general ophthalmic services costs: £484 million, hospital expenditure: £593 million, costs associated with injurious falls: £25 million) and £4.34 billion indirect costs (including £2.03 billion informal care costs). The total costs also include £16 billion burden of disease costs, which put a monetary value on individuals losing quality of life because of sight loss.15

Increases in wet AMD patient numbers are expected to be continuous because of the long-term nature of the disease, as well as the ageing population. Pressures on clinical capacity in the hospital eye service (HES) may also be compounded in the future by new indications for intravitreal treatments and the availability of future new treatments for retinal diseases such as diabetic macular oedema (DMO) and retinal vein occlusion (RVO).16, 17, 18 Slow-release preparations for wet AMD are being developed, but may not be available for some time. Furthermore, the United Kingdom has the lowest ratio of consultant ophthalmologists per 100 000 of the general population in the European Union.19

It is clear that robust and long-term retinal service models must be rolled out in order to meet the needs of local populations both currently and in the future. Action on AMD strongly advises that every hospital with a retinal service start this process now, so that there is no compromise later in the standard of service provision, duration of follow-up, and quality of intravitreal treatment administration. Fast-track patient referral systems from primary care combined with prompt commencement of therapy in ophthalmology care and regular monthly follow-up, as per NICE guidance and Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) guidelines, are vital to the management of patients with wet AMD. There must be no compromise to patients’ safety, efficacy of the treatment, or patient outcomes.

Key capacity issues

Modelling exercises (using national averages) have shown that the number of assessment appointments drives the need for increased capacity rather than the number of intravitreal injection appointments (unpublished data provided by Novartis). Thus, patient follow-up appointments are usually the bottleneck. This is important as the evidence shows that, with current licensed and recommended treatment, frequency of follow-up appointments for wet AMD patients must continue to be monthly and cannot be reduced without compromising patient outcomes.20

It follows that a solution for many providers involves increasing capacity within follow-up clinics. In some HES facilities, pressure on optical coherence tomography (OCT) clinical imaging services is being aggravated by the increasing use of OCT imaging for other ophthalmic disorders such as glaucoma, and recent guidance from NICE requiring optic disc imaging in glaucoma patients.21 Action on AMD has identified a number of key capacity issues that are summarised in Table 1. Although these are commonly occurring issues, Action on AMD acknowledges that not all of these issues will apply to every clinic.

Clinical capacity issues largely fall into one of five categories, relating to the following: (1) clinic space—shared with other services or limited in physical size; (2) staffing—shortages in numbers of key staff and/or inadequacies in skills and training; (3) equipment—insufficient, equipment used is not the best available, or other clinical pressures for use of equipment; (4) support and quality—suboptimal provision of patient support or inability to carry out monthly monitoring of patients; (5) funding—business case is either inaccurate, not sufficiently long term, not agreed, or not implemented. The consequences of these issues are serious and threefold:

-

Clinics run at maximum capacity with no scope for further expansion of service. They may even be unable to cope with the current patient numbers and may not provide the recommended standard of care.

-

Inferior or compromised patient quality of care, which may be detrimental to patients’ quality of life and disease outcomes.

-

Substantial pressure on staff.

Possible approaches and key considerations: case studies

Individual wet AMD provider services differ in their structure, size, and patient population, as well as in the specific limitations of the service. Thus, it is highly unlikely that one single solution will be suitable for every clinic. Instead, Action on AMD believes that there are a number of possible solutions. In addition, Action on AMD believes that it is useful to learn from clinical service models that work. We have therefore shared some exemplar case studies here including examples where novel solutions and models have been used successfully, to illustrate that current capacity problems are not insurmountable. These case studies span a range of useful solutions and can be implemented with or without further local adaptation. For implementation of change, the key is to implement a particular model. The specifics of the roles of different professional groups will need to be defined but should not be the primary focus.

Exemplar case study: expanded roles for non-consultant clinical staff (Gloucestershire)

Gloucestershire provides a one-stop clinic service, with assessment and treatment clinics running in parallel. Non-consultant staff—particularly nurse practitioners and optometrists—take key roles, helping to maximise capacity and maintain monthly follow-up of patients.

Service structure. Initial assessment of new patients is led by optometrists and nurse practitioners who take the patient's history and perform primary examinations (including early treatment diabetic retinopathy study (ETDRS) visual acuity, VA) and diagnostic imaging (Figure 1). All data are recorded in an Electronic Medical Record (EMR; Medisoft®, Medisoft Limited, Leeds, UK) system. If wet AMD is suspected, the diagnosis is first confirmed at specialist clinics using fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) before the patient is referred to the wet AMD treatment clinic. This ensures a homogeneous patient population in the wet AMD clinic and stereotyped clinical care. An optometrist undertakes refraction at presentation and annually. OCT technicians work with optometrists to collect OCT and slit lamp data. Nurse practitioners perform LogMAR VA analysis and measure best corrected visual acuity (BCVA). Because all clinical data are recorded electronically, the retinal consultant is able to make rapid treatment decisions for new and returning wet AMD patients using the EMR. If necessary, the consultant ophthalmologist can also view previous OCT scans on the EMR and examine the patient themselves. As the nurses and optometrists gain experience, they are able to make clear ‘observe’ and obvious ‘re-treat’ decisions. If intravitreal treatment is required, a second retinal specialist administers the injection, assisted by two nurses who assist with injection preparation.

If, after 18 months from first referral, a patient has not required an intravitreal injection for at least 6 months, they are moved to an optometrist-led stable AMD clinic to ease pressure on the assessment clinic.

Clinic capacity. Three assessment/treatment clinics take place per week, each comprising 40–45 follow-up assessments, 5–8 planned initial injections, and approximately 15–25 ‘as required’ injections. Eight to ten patients are examined per session in the stable clinic, and frequency depends on patient numbers.

Key requirements. An EMR system is required, as well as networked OCT instruments. Development of nurse practitioner and optometrist skills have been necessary, to be able to perform the necessary examinations and record data in the EMR. It can also become possible for nurses to make clear ‘observe’ and ‘re-treat’ decisions. For the assessment clinic, three nurses perform LogMAR BCVA and three pairs of OCT technicians and optometrists carry out OCT and slit lamp examinations. One medical retinal consultant moves between the three clinical assessment rooms. Two nurses and one other retinal doctor are required for the treatment clinic and, for the stable clinic, one hospital-based optometrist is required. There is one full-time clinic coordinator, but secretarial support is reduced as correspondence is automatically generated by the EMR system.

Learning points

Exemplar case study: The Mobile Community Eye Care Project, design and commission of a mobile eye care clinic for wet AMD (York)

The Mobile Community Eye Care Clinic (MCECC) is a purpose-built, one-stop mobile clinic, designed to increase capacity for the management of wet AMD patients. Its mobility enables it to be used at a number of different sites during the 4-week cycle of wet AMD care, abolishing the need for multiple static sites. It functions in conjunction with the hub site, which remains the diagnostic centre.

Service structure. Patients diagnosed with wet AMD at the hub site can be referred to the MCECC for follow-up and treatment. The MCECC has facilities for measuring VA, including an optometrist facility for performing initial, 12-monthly and ‘as needed’ refraction (Figure 2), as well as retinal imaging facilities (OCT), slit lamp, and intraocular pressure (IOP). If the consultant decides that treatment is needed, an initial dosing regime is initiated (doses are administered at 4-week intervals) in a dedicated treatment room. Patients at high risk of needing further treatment are followed up every 4 weeks and are suited to a one-stop service, with consultant-led assessment clinic and treatment at the same visit. Patients at a low risk of needing further treatment can either be assessed and treated if necessary at the MCECC or assessed by community optometrists and referred to the MCECC for treatment as a two-step process that may be more convenient for the patient.

Clinic capacity. The MCECC has capacity for two optometrists and two OCT instruments. It is estimated to be able to increase the capacity of an existing ophthalmic clinic by 40–50 patients per day.

Key requirements. The mobile clinic is assembled on site from three articulated lorry trailers. A 2.5 h assembly time and overnight/weekend relocation enable seamless continuity of the service. The MCECC is staffed by the local hospital staff, or additional staff can be offered to run the service under overall control and governance of the local HES. Contracted maintenance staff are provided (driver, management, and emergency cover), and thus local units only need to be involved in clinical management. The unit includes imaging equipment, core patient database and electronic patient records (including audit tool), disabled access, a staff room, and a dedicated intravitreal treatment clean room.

Learning points

Exemplar case study: nurse-led rapid access clinics and virtual review clinics (Sheffield)

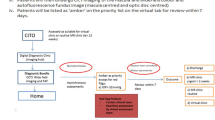

A rapid access clinic led by a nurse consultant has been set up in Sheffield. This clinic allows new patients to be triaged to the appropriate clinic on the basis of initial assessments, allowing the consultant ophthalmologist's time to be utilised more effectively. In addition, nurses also lead the photographic review clinic for returning patients, helping to relieve clinical workload of large numbers of monthly follow-up patients.

Service structure. A two-stop model allows the workload to be planned and is suitable for the urban Sheffield area, as most patients only travel short distances. New referrals are examined at a weekly nurse-led rapid access clinic, with any overflow being booked into the doctors’ clinic (Figure 3). Patients are assessed, diagnosed, and triaged by the nurse and referred appropriately. Information about intravitreal treatment is given to the patient by the nurse, where appropriate. For wet AMD patients, images and notes are discussed in a weekly reporting session (virtual clinic) involving a multidisciplinary team, during which treatment decisions are made. If appropriate, patients are then booked in for intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment by the clinic coordinator. Treatment is administered by a retinal consultant in a dedicated minor operations theatre. Four-weekly photographic reviews are carried out in a nurse-led clinic with dedicated ophthalmic imaging room and a team of ophthalmic photographers, allowing for multiple patients to be examined simultaneously. Images are reviewed by the medical consultants and nurse consultant at the weekly reporting session, allowing timely and appropriate management. Where necessary, some patients may receive photographic review and intravitreal injection on the same day.

Nurse-led and virtual patient pathway (Sheffield example). AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BRVO, branch retinal vein occlusion; CSR, central serous retinopathy; FA, fluorescein angiography; ICG, indocyanine green angiography; IVT, intravitreal treatment; OCT, optical coherence tomography; VA, visual acuity.

Clinic capacity. Three rapid access and review clinics are held per week, with a total of 35 patients assessed per week. There is a weekly capacity of 84 patients on the intravitreal injection lists and 84–90 patients in the photographic review clinics. Four reporting sessions are held per week.

Key requirements. A key requirement of this service is a senior nurse or nurse consultant who is able to lead the rapid access clinic (including requesting medical imaging, cannulation and administration of contrast medium, diagnosis of other pathologies, talking to patients about findings, triaging, and referring to low vision assessment services or other appropriate clinic), is involved in review of retinal images at the reporting sessions (alongside the medical consultants), can list patients for treatment and re-treatment, and can prescribe anti-VEGFs. Ophthalmic staff nurses who can undertake the photographic review clinics are also required. Sheffield has four such nurses at present. Experience from Sheffield is that two AMD clinic coordinators are required to organise the clinics and intravitreal treatment lists, liaise directly with patients to ensure timely treatment, organise patient transport, data capture, and provide patients with the outcome of their photographic review.

Learning points

Exemplar case study: utilisation of a peripheral clinic and mobile screening (Southampton)

A peripheral clinic was originally set up to complement the Southampton Eye Unit, easing pressure on clinic space at the main hospital eye unit and resulting in a more patient-friendly service. Furthermore, a mobile assessment unit is now being developed, to provide an even more convenient service for patients and reduce transport costs.

Service structure. Initially, a peripheral clinic was set up in a large health centre, with facilities for OCT imaging and intravitreal injections. Patients were diagnosed and had their first injection at the main hospital eye unit (Figure 4). Subsequently, they were booked for injections or follow-up at the peripheral health centre, providing a one-stop service. The service at Southampton no longer uses the peripheral clinic at the health centre. Instead, follow-up patients from three peripheral hospitals will attend a mobile assessment unit (stationed at the local hospital) for assessment of VA and OCT imaging. A medical retinal consultant at the main hospital eye unit will review the images, and, if necessary, patients will be booked for treatment at the peripheral hospital.

Clinic capacity. Southampton Eye Unit currently undertakes ∼20 OCT scans per instrument per session (and has two OCT instruments), with 600–700 patients seen per month and around 300 intravitreal injections administered per month. The OCT scan van is expected to have capacity to screen 10 patients per session, and ∼30 OCT images are expected to be reviewed per virtual session by the ophthalmologist.

Key requirements. The peripheral clinic required an OCT instrument, operated by a clinical photographer and an ophthalmologist to assess the patients. A second ophthalmologist performed the intravitreal injection, assisted by a nurse. For mobile assessment, in addition to the van itself, equipment and staff are required for OCT fundus imaging and VA assessment. There is a need for high-quality IT to enable large file-size images to be sent from the van to the main unit for assessment by the retinal specialist.

Learning points

Exemplar case study: flexible multidisciplinary approach to patient management and satellite macular clinics in the community (Sunderland Eye Infirmary)

Sunderland Eye Infirmary (SEI) uses a teamwork approach that extends the role of hospital optometrist, nursing, and health-care staff as ‘macular specialist staff’ for provision of a service in an area with higher than average incidence of wet AMD.

Service structure. All new patient referral requests are directed by rapid access referral to a named ‘on take’ medical retinal consultant who allocates the patient either to triage or directly to the AMD specialist clinic (Figures 5a and b). Triage clinics are undertaken by hospital optometrists to identify any false-positive wet AMD referrals and redirect patients appropriately. All patients in whom wet AMD is suspected are reviewed by a medical retinal consultant, and those requiring intravitreal treatment have the choice of immediate (one-stop) treatment or joining a dedicated intravitreal injection list (two-stop). An Eye Clinic Liaison Officer (ECLO) undertakes a session simultaneous to the specialist clinic so that patients requiring support can undergo disability assessment and visual rehabilitation during the same visit. If a patient has not required treatment for 6 months, they are followed-up in a nurse-led review clinic. When patients remain stable after 24 months from start of treatment, they are seen in an optometrist-led OCT clinic. ‘Stable’ patients can be seen at satellite clinics closer to their home, and a mobile OCT scanner travels to the satellite clinics.

(a) Hub and satellite clinic spoke (Sunderland example). The pathway for newly diagnosed patients and patients with ‘active’ wet AMD. AMD, age-related macular degeneration; FFA, fundus fluorescein angiography; IVT, intravitreal treatment; MR, medical retinal; OCT, optical coherence tomography; VA, visual acuity; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Clinic capacity. In all, 15–20 patients are examined at each of 2 weekly triage clinics. The AMD specialist clinics are run six times a week each with capacity for 8 new patients and 24 follow-up patients, and 17 injection slots. In addition, five dedicated injection lists per week increase throughput with 15–20 injections per session. Each week there are up to three nurse-led AMD review clinics with 15 patients each and two optometrist-led OCT review clinics with 30–35 patients each.

Key requirements. Good teamwork is vital to provide patients with the best health care, and the SEI Macular Unit staff are flexible in their roles, to ensure efficient and effective delivery of the treatment. The staff comprises three medical retinal consultants, two general ophthalmologists, three optometrists, four macular specialist nurses, two health-care assistants, an ECLO, two medical photographers, a macular secretary/AMD coordinator, and three reception staff. A dedicated macular unit consisting of a nursing assessment area, imaging suite, preparation rooms, and injection suite has been established for the macular patients.

Learning points

Exemplar case study: e-referral link between community optometrists and hospital eye clinics (Fife)

In the autumn of 2010, the Scottish Government announced a £6.6 million investment in a new IT scheme linking community optometrists and eye clinics within hospitals across all of Scotland.22 The link was based on a successful pilot scheme in NHS Fife and allows optometrists to send clinical images of patients with potentially serious eye problems (such as wet AMD) directly to ophthalmologists, enabling them to decide on the same day whether the person needs a hospital ophthalmology appointment. Future development of this service is expected to reduce the time between patients visiting the optometrist and receiving an appointment from the HES and lead to fewer unnecessary hospital attendances.

Service structure. In the previously published pilot study,23 patients visiting one of three optometry practices with existing non-mydriatic cameras were charged a small fee for fundus photography, and the images were forwarded by email to the HES using NHSmail (www.nhs.net), accompanied by the electronically redesigned referral form (Figure 6). Each referral was assessed by a consultant ophthalmologist whose telemedicine assessment was based solely on the information and image provided in the referral. The decision for requiring or not requiring an appointment within the HES was communicated to the optometrist by email, and to the patient and GP by letter.

Telemedicine with community imaging (new vs old Fife patient pathways). Adapted from Cameron et al. with permission from the Nature Publishing Group.23 GP, general practitioner; HES, hospital eye service.

Clinic capacity. In an 18-month trial, 346 patients were examined. Of these, 128 patients (37%) were found not to require an HES appointment, considerably easing the burden on the hospital eye unit. The potential cost savings of such a scheme are estimated to run into several hundred thousands of pounds per annum for individual hospital trusts.23

Key requirements. Suitable quality retinal imaging cameras for community optometrists are required. High-quality IT equipment is also required, as well as special approval to send large files containing confidential clinical information via NHSmail. An appropriately designed e-referral form is necessary to ensure that all relevant information is captured in primary optometric care for accurate decision-making by a remote secondary-care specialist.

Learning points

Exemplar case study: telemedicine pilot project with OCT image transfer from community optometry to ophthalmologist; teleophthalmology (Salford/Bolton)

In the first phase of a pilot project, a community optometry practice in Salford forwarded consecutive e-referrals with attached OCT images of retinal patients to a consultant ophthalmologist based at Royal Bolton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. These cases received rapid referral telemedicine advice and triage or teleophthalmology.

Service structure. In a pilot study, 43 retinal patients were assessed during the period June 2010–June 2011. The OCT images of patients’ retinae were captured and stored locally by the optometrist and then forwarded using NHSmail (www.nhs.net) as JPEG files to the hospital consultant ophthalmologist (Figure 7). Patients were charged a small fee for the enhanced imaging. In the pilot project, the consultant ophthalmologist typically responded within 24 h by remote telemedicine working. The next phase of the pilot study aims to secure funding to expand the service to wider eye conditions and make OCT imaging available to potential participants who may be unable to pay for community optometrist OCT imaging.

Community OCT telemedicine (example from Salford/Bolton). OCT, optical coherence tomography. Reprinted from Kelly et al.24 Copyright 2011, with permission from Dove Medical Press Ltd.

Key requirements. OCT imaging in primary care requires equipment, as well as skill in taking and transmitting appropriate images by the community optometrist. In addition, the secure email transfer and centralised data storage systems between different health-care providers need to be compatible. For roll-out of this model, relevant primary and secondary, private and NHS health-care practitioners require access to NHSmail or N3 connection to enable secure patient data transfer. A dedicated NHSmail inbox for receipt of all electronic referrals at Trusts may be of benefit, but would need to be supported by appropriate resourcing, to provide continuous management of electronic referrals. For further details on this exemplar case study, see Kelly et al.24

Learning points

Service innovation, summary of approaches

Possible approaches to the various key capacity issues are summarised in Table 2. Overall, the general considerations for each of these potential solutions include costs, staff retention and morale, staff training and competency assessment, availability (of space, staff, or equipment), staff leave of absence, management of complications (eg, safety), and patient acceptance. Other challenges and considerations that are specific to each possible approach are also described in Table 2 and are drawn from the case studies and expert experience. Whatever the specific problem areas that need to be addressed, effective stakeholder engagement must inform the approach chosen, including engagement with patients and patient organisations.

Conclusions and summary

Wet AMD services in many parts of the UK NHS are under pressure and often running to maximum capacity. It is vital that services continue to adapt locally to meet current and future demands, so that they may continue to provide the best care possible for patients with wet AMD. There is evidence from patient safety reports from the NHS and in a survey undertaken by RCOphth that capacity has been problematic, at times, in the HESs in the United Kingdom.25, 26 Failure to maintain the recommended follow-up interval can cause patients to unnecessarily lose vision permanently, with a consequent burden on health and social care.

Action on AMD aims to assist eye health-care professionals and NHS commissioners and providers rise to the challenge of increasing wet AMD rates and provide access to optimum care for these NHS patients. Action on AMD strongly advises that every hospital with a medical retinal clinic evaluate their wet AMD service and, wherever necessary, implement modifications to ensure that the best possible quality of care is currently provided, and continues to be provided into the future. We are aware of pockets of good practice and service development.

In accordance with the government's pledge to support the NHS in providing high-quality and patient-centred care, the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) programme aims to ensure that all money spent in the NHS is used to bring the most benefit and quality of care to patients. The Quality Standards Group of RCOphth has produced a self-assessment tool for a number of clinical services, including wet AMD. This tool indicates whether a department is currently providing an acceptable standard of patient care and can be used as a quality improvement tool to show where the service is under stress. Action on AMD supports such an approach that could be applied to pinpoint which of the potential solutions presented here would best improve the quality of patient care in any particular clinic.

Importantly, we have presented here a number of potential solutions that experience has shown to improve quality, effectiveness, and productivity, and thus increase capacity. The examples provided can be implemented in whole, in part, or in principle, at a local level, and our key recommendations are summarised in Table 3. For implementation of change, the broader principle of adopting a particular model is more important than the specifics of which professional group to use. In our opinion, services for wet AMD patients require clinical leadership, and, in our opinion, ophthalmologists with expertise in the management of wet AMD must be supported by appropriately trained staff, equipment, and clinical space. Although investment may be necessary to modify existing services, this can be outweighed by the provision of better quality care that meets the needs of patients, increased productivity by maximising the use of experienced clinicians, and additional revenue to be invested in the HESs. Importantly, we would also expect cost reductions in the long term in sight support services (both health and social care) as more patients retain vision with better clinical outcomes.

References

Owen CG, Fletcher AE, Donoghue M, Rudnicka AR . How big is the burden of visual loss caused by age related macular degeneration in the United Kingdon? B J Ophthalmol 2003; 87: 312–317.

Bunce C, Wormald R . Causes of blind certifications in England and Wales: April 1999-March 2000. Eye 2008; 22: 905–911.

NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance TA155. Ranibizumab and pegaptanib for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. 2008. Accessed at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA155guidance.pdf.

Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CCW, Klein R, Munoz B, Friedman DS et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122: 477–485.

Bressler NM, Arnold J, Barbazetto I, Birngruber R, Blumenkranz MS, Bressler SB et al. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119: 198–207.

Mitchell J, Bradley C . Quality of life in age-related macular degeneration: a review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006; 4: 97–117.

NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance TA68. Photodynamic therapy for age-related macular degeneration. 2003. Accessed at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11512/32728/32728.pdf.

Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Commissioning contemporary AMD services: a guide for commissioners and clinicians. 2007. Accessed at http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/core/core_picker/download.asp?id=181&filetitle=Commissioning+Contemporary+AMD+Services.

Brown DM, Michels M, Kaiser PK, Heier JS, Sy JP, Ianchulev T . Ranibizumab versus verteporfin photodynamic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results of the ANCHOR study. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 1, 57–65e5.

Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, Boyer DS, Kaiser PK, Chung CY et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1419–1431.

Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, Soubrane G, Heier JS, Kim RY et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1432–1444.

Bressler NM, Chang TS, Suner IJ, Fine JT, Dolan CM, Ward J et al. Vision-related function after ranibizumab treatment by better- or worse-seeing eye. Ophthalmol 2010; 117: 747–756.

Bressler NM, Chang TS, Fine JT, Dolan CM, Ward J . Improved vision-related function after ranibizumab vs photodynamic therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 2009; 127 (1): 13–21.

Chang TS, Bressler NM, Fine JT, Dolan CM, Ward J, Klesert TR . Improved vision-related function after ranibizumab treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 2007; 125 (11): 1460–1469.

RNIB. Future Sight Loss UK (1). The economic impact of partial sight and blindness in the UK adult population. 2009. Accessed at http://www.rnib.org.uk/aboutus/Research/reports/2009andearlier/FSUK_Report.pdf.

The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Edwards AR et al. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2010; 117 (6): 1064–1077.

Campochiaro PA, Heier JS, Feiner L, Gray S, Saroj N, Rundle AC et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 2010; 117 (6): 1102–1112.e1.

Brown DM, Campochiaro PA, Singh RP, Li Z, Gray S, Saroj N et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 2010; 117 (6): 1124–1133.

Ocular Surgery News Europe Edition. Growing demand for eye care services may highlight shortage of ophthalmologists in Europe. 2010. Accessed at http://www.osnsupersite.com/view.aspx?rid=65866.

Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, Dubovy SR, Michels S, Feuer W et al. A variable-dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: year 2 of the PrONTO study. Am J Ophthalmol 2009; 148 (10): 43–58.

NICE Clinical Guidelines CG85. Glaucoma. 2009. Accessed at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12145/43887/43887.pdf.

The Scottish Government. Roll-out of IT services for optometry. News release. 2010. Accessed at http://www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2010/09/27113039.

Cameron JR, Ahmed S, Curry P, Forrest G, Sanders R . Impact of direct electronic optometric referral with ocular imaging to a hospital eye service. Eye 2009; 23: 1134–1140.

Kelly SP, Wallwork I, Haider D, Qureshi K . Teleophthalmology with optical coherence tomography imaging in community optometry. Evaluation of a quality improvement for macular patients. Clin Ophthal 2011; 5: 1673–1678.

Kelly SP, Barua A . A review of safety incidents in England and Wales for vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor medications. Eye 2011; 25: 710–716.

Royal College of Ophthalmologists. AMD Services Survey. Royal College of Ophthalmologists: London, 2009. Accessed at http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/page.asp?section=295§ionTitle=AMD+Services+Survey.

Acknowledgements

An expert capacity working group was formed in May 2010, and support for initial meeting expenses and logistics was provided by Novartis. A report was generated by the meeting, which formed the basis of this document. Novartis has had the opportunity to review this document for technical accuracy but has had no editorial input. We thank Sue Harris from ApotheCom who provided medical writing support on behalf of Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Mr Amoaku chaired the Scientific Committee of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists from 2007 to 2011, and currently chairs the College's Medical Retina Service Provisions Subcommittee, and the VISION 2020 UK Macular Interest Group. He is a member of the Scientific Research Committee of the Macular Diseases Society. He has received educational travel grants from Allergan, Novartis Pharma and served on Advisory Boards for Allergan, Bayer, Novartis, and Pfizer for which he has received honoraria. He has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis, Pfizer, and Bausch and Lomb, for which his institution has received funding. His institution has also received research grant funding from Allergan and Novartis. He has received lecture fees for speaking at the invitation of Allergan, Bausch, Lomb, and Novartis. Susan Blakeney is Optometric Adviser to the College of Optometrists and to the Primary Care Trusts in Kent and Medway. She is also a director of BP Eyecare Ltd, which has received consultancy fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK. Mary Freeman has received an honorarium for supporting an annual symposium on AMD for nurses and allied health-care professionals, and for advisory consultation from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK. Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust conducts clinical trials sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK. Richard Gale is Chairman of The Eye Site Clinic Ltd and Mobile Healthcare Accommodation Ltd, and has received educational grants from, and advisory consultation for, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK. He has received lecture fees for speaking at the invitation of Abbott and Novartis. York Teaching Hospital conducts clinical trials sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK. Simon Kelly has attended advisory consultation board meetings and educational travel support with Allergan, Novartis, and Pfizer. He has received lecture fees from Novartis. The Royal Bolton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust is involved in clinical research sponsored by Novartis and Allergan. Barbara McLaughlan has no conflicts of interest to declare. Her former institution, RNIB, received limited unrestricted educational grants from Novartis. Deepali Varma has attended advisory board meetings for Novartis and Allergan. Sunderland Eye Infirmary has participated in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK and Allergan UK. Rob Johnston is the Medical Director of, and is a shareholder in Medisoft Limited. He has received lecture fees and travel grants for speaking at the invitation of Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK. He received consulting fees from Bayer in 2011. Debendra Sahu has received educational grants and advisory consultation from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK and Allergan Ltd UK. Southampton General Hospital NHS trust conducts clinical trials sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK.

Additional information

Please note that prescribing information is available at the end of this supplement.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Amoaku, W., Blakeney, S., Freeman, M. et al. Action on AMD. Optimising patient management: act now to ensure current and continual delivery of best possible patient care. Eye 26 (Suppl 1), S2–S21 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2011.343

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2011.343

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Save our Sight (SOS): a collective call-to-action for enhanced retinal care across health systems in high income countries

Eye (2023)

-

The ideal intravitreal injection setting: office, ambulatory surgery room or operating theatre? A narrative review and international survey

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2023)

-

Anti-VEGF therapies for age-related macular degeneration: a powerful tactical gear or a blunt weapon? The choice is ours

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2021)

-

Predicting conversion to wet age-related macular degeneration using deep learning

Nature Medicine (2020)

-

Action on neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD): recommendations for management and service provision in the UK hospital eye service

Eye (2019)