Abstract

Increasing cancer incidence together with improved survival rates are contributing to the growing number of cancer survivors. Survivors may encounter a range of potential effects as a result of the cancer itself or cancer treatments. Traditionally, the major focus of follow-up care has been on detection of cancer recurrence; however, the efficacy of such strategies is questionable. Traditional follow-up frequently fails to identify or adequately address many survivors’ concerns. Aftercare needs to be planned to enable better outcomes for survivors, while using scarce health-care resources efficiently. This review focuses on provision of survivorship care, rather than on research. England’s National Cancer Survivorship Initiative has developed principles for improved care of those living with and beyond cancer. These include risk-stratified pathways of care, the use of treatment summaries and care plans, information and education to enable choice and the confidence to self manage, rapid re-access to specialist care, remote monitoring and well-coordinated care. Many of these principles are relevant internationally, though preferred models of care will depend on local circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Throughout the world cancer prevalence, or the number of people living with and beyond cancer, is increasing. In developed countries this is at least partly due to the ageing population and improved cancer detection. Survival rates have improved substantially over recent decades. For example, in the United States five-year survival rates for all cancers combined improved from 49% in the period 1975–1977 to 67% in the period 2001–2007 (Siegel et al, 2012). Around 80% of children with cancer will be long-term survivors. In 2008 there were an estimated 2 million individuals living with and beyond a diagnosis of cancer in the United Kingdom (Maddams et al, 2009). There are an estimated 12.5 million cancer survivors in the US (Howlader et al, 2012).

Defining cancer survivorship

The term ‘cancer survivor’ is used to refer to different populations of people with an experience of cancer. In the United States, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) ‘defines someone as a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis and for the balance of life’ (National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, 2012). Family members, friends and caregivers are included in this definition. More traditionally, a cancer survivor has been considered someone apparently cured of cancer. Measures such as five-year disease-free (or overall) survival have marked long-term survivorship. A more recent emphasis has been on the period following potentially curative treatments for cancer. The influential US Institute of Medicine (IOM) report ‘From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition’ focuses on this period (Hewitt et al, 2006). Within the United Kingdom, cancer survivorship has generally referred to the period after completion of initial treatment, regardless of whether the person is free from cancer at that time (Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS Improvement, 2010). Not all are comfortable with the term ‘survivor.’ One alternative is ‘living with and beyond cancer.’

The challenges around cancer survivorship

Survivors may encounter a range of potential issues as a result of the cancer itself and cancer treatments (Hewitt et al, 2006). Cancer may cause significant physical, psychosocial, spiritual and existential effects. There can be a range of practical consequences, including loss of income, limitations on work and school performance and change in roles. Effects may pass relatively quickly (e.g., hair loss or nausea), or be long-term or permanent (e.g., infertility). Some effects may not arise for months or years after completion of treatment, so called ‘late effects’ (e.g., cardiomyopathy or the development of a second cancer) (Hewitt et al, 2006).

Many survivors feel anxious about leaving the safety of the cancer care system when they transit from end of treatment to long-term follow-up (Jefford et al, 2008). Fear of cancer recurrence and uncertainty about the future are common issues for both survivors and caregivers (Hewitt et al, 2006; Jefford et al, 2008).

Although survival rates have improved dramatically for children with cancer, there has been growing recognition of the many potential consequences of cancer and its treatment. A study of over 10 000 survivors found the cumulative incidence of a chronic health condition 30 years after cancer diagnosis was 73.4% (Oeffinger et al, 2006). Compared with siblings, the adjusted relative risk of a chronic condition was 3.3 (95% CI, 3.0–3.5) and for a severe or life-threatening condition the adjusted relative risk was 8.2 (95% CI, 6.9–9.7) (Oeffinger et al, 2006). It is imperative that health economies recognise and develop services to deal with the many consequences of cancer treatments.

Traditional follow-up for cancer patients

Historically, the major focus of cancer follow-up has been the detection of cancer recurrence. Although for colorectal cancer there is evidence that intensive follow-up may improve survival (Jeffery et al, 2007), there is limited data to support regular review for many other cancers. For women with breast cancer, the majority of recurrences are identified after the development of symptoms and between scheduled clinic visits. Intensive follow-up and clinical examination appears to have limited efficacy (Grunfeld et al, 1996; Montgomery et al, 2007).

Patients frequently report that their psychological and other supportive care needs are neither identified nor addressed (Adler and Page, 2008). Beaver and Luker (2005) studied the nature and content of hospital follow-up for women with early-stage breast cancer. Consultations were generally quite short (mean duration of 6 min) and focussed on detection of recurrence. Few opportunities were available to meet supportive care needs.

The earlier referenced IOM report defines four goals of survivorship care: prevention and detection of new cancers and recurrent cancer; surveillance for cancer spread, recurrence or second cancers; interventions to deal with the consequences of cancer and its treatment; and coordination between specialists and primary care providers (Hewitt et al, 2006). The current approach to aftercare does not adequately meet these goals.

Barriers to ideal post-treatment care

There are significant barriers to ideal post-treatment care. Understandably, the focus of cancer care has been on cure. The emphasis of care is on prompt diagnosis and treatment. Unlike other health-care settings, for example after heart attack or stroke, there has not been an emphasis on post-treatment rehabilitation.

It is possible that cancer specialists are not aware of alternative models of post-treatment care. Care in the community is acceptable and safe, at least in defined circumstances (Grunfeld et al, 2006; Lewis et al, 2009b). Nurse-led follow-up is an alternative to physician-centred care (Lewis et al, 2009a) and non face-to-face review, such as by telephone, may be equally effective (Davies and Batehup, 2011).

In many circumstances there is a lack of evidence-based guidance regarding aftercare (Davies and Batehup, 2011). Important questions need addressing: How often should people be reviewed? In what way? With what investigations? Using what tools to screen for survivorship issues? Who are the right people to be involved in post-treatment care? How much responsibility rests with survivors themselves, and how much with various care providers? These may all be influenced by factors such as cancer type, treatments received, circumstances of the patient and local health and social care infrastructure. Richardson et al (2011) have provided a recent description of research priorities concerning the post-treatment survivorship phase.

In many health-care settings funding models support the status quo. Reimbursement is generally tied to face-to-face reviews, rather than considering interactions by e-mail or telephone, or group-based education and training. Reimbursement or structural reasons may mean that supportive care or rehabilitation services are not available to those who need them. Patients and carers have high expectations regarding ongoing follow-up. Service users and health professionals prefer a method of follow-up they have experienced, suggesting possible resistance to alternative models (Frew et al, 2010).

The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative

Health care is provided free at the point of use to all residents within the United Kingdom. The vast majority of care in England is provided through the National Health Service (NHS), which covers primary, secondary and tertiary care. The Department of Health has responsibility for the NHS. There is a small private health-care system.

The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (NCSI) was announced in the Cancer Reform Strategy (2007) and formally launched in September 2008. The NCSI is a partnership between the Department of Health (England), NHS Improvement and Macmillan Cancer Support, a large British cancer charity.

Vision

The vision of the NCSI is that those living with and beyond cancer are supported to live as healthy and active a life as possible, for as long as possible. Important informative data were derived from the study undertaken by Frew et al (2010) involving survivors, carers and a range of health professionals. A broad range of patient, carer, health-care professional, voluntary sector, academic, research, international expert and government representatives with a special interest, expertise, sphere of influence or responsibility for developing health-and social-care provision for cancer services at a national or international level attended a think tank event in March 2008. From this a number of work streams were established. To inform their work two reviews of all published and grey research on survivorship were commissioned in order to inform programme development and research directions.

The NCSI launched its vision document in January 2010, describing five important shifts in the approach to care and support of people living with and beyond cancer (see Box 1; Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS Improvement, 2010).

Work streams

The bulk of initial work of the NCSI was organised around seven work streams (Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS Improvement, 2010). Working groups comprised survivors, carers, representatives from cancer charities, health- and social-care staff and researchers (see www.ncsi.org.uk; Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS Improvement, 2010). Three of the work streams dealt with steps in the survivorship pathway: assessment and care planning; consequences of cancer and treatment, and active and advanced disease. A further three were cross cutting, covering the whole survivorship pathway: work and finance; supported self-management and research. The work stream for survivors of childhood and young peoples’ cancers covers the whole survivorship pathway, but for a particular age cohort. Each stream was asked to consider issues relating to patient information, commissioning and workforce (Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS Improvement, 2010). Consensus was built through the work streams focusing on specific issues while taking an inclusive approach to engage professional bodies and organisations within the cancer field, and was informed by several topic-specific evidence reviews. ‘Learn and share’ workshops ensured regular opportunities for test communities to share learnings and annual conferences ensured these lessons reached wider audiences.

Clinical testing

The clinical improvement section of England’s NHS (NHS Improvement) supported the delivery of the NCSI, through piloting models of improved care and support for childhood and adult survivors. Many test sites throughout England conducted pilot projects (see www.ncsi.org.uk). For adult cancers, subsequent testing has evaluated agreed risk-stratified pathways of care for people living with and beyond breast, colorectal, lung or prostate cancer. The goals of these re-designed pathways of care are three-fold: (1) an improvement in survivors’ experience and patient-reported outcomes of care from baseline; (2) a 50% reduction in outpatient attendances from the traditional model, and (3) a 10% reduction in unplanned admissions from baseline (NHS Improvement, 2012).

Principles of risk-stratified pathways of care

Several key principles underpin the re-designed care pathways for survivors of young people’s and adult cancers (NHS Improvement, 2011):

(1) Care is personalised and delivered according to pathways that are risk-stratified on the basis of cancer type and treatments received as well as individual needs, preferences and circumstances (see Figure 1). The implication is that aftercare should not be ‘one size fits all’ but informed by the likely or possible consequences of treatments. Individual needs will vary and thus the health-care system must be adaptable to meet these needs. Individuals will have different preferences around follow-up and self-management.

(2) All survivors should be offered a treatment summary and personalised care plan. This is consistent with recommendations from the IOM (Hewitt et al, 2006). To support self-management, the care-planning process should be supported by appropriate information and education. An initial evaluation of survivorship care plans showed they did not improve PROMs in an unselected population of breast cancer survivors (Grunfeld et al, 2011). Several authors have noted the significant time required to complete detailed treatment summaries. Added to this is the time required to complete holistic needs assessment/psychosocial screening and to then discuss the treatment summary and care plan. Whether all survivors require the same level of care planning is uncertain at this time, but needs to be considered recognising the major time impost. It is also uncertain who might be best placed to do this work and in what setting—specialists (oncologists, cancer nurses) in an oncology setting, general practitioners or others in the community, or others. In England, the care plan is seen as an important part of a care package aimed at empowering patients to manage their own condition more effectively. Large-scale surveys will assess whether this influences either patient experience of care or their quality of life.

(3) Rapid re-access to the appropriate part of the health-care system is essential if there is concern of cancer recurrence or if individuals need to access specialised cancer care for any other reason.

Two key enablers of the re-designed pathways of care are remote monitoring and care coordination:

Systems for remote monitoring enable people to have tests (e.g., tumour marker blood tests or surveillance scans) without the need to attend a health-care provider either for the test request or for the results. This requires a robust system for results to be communicated to survivors and their health-care providers, while allowing people to be recalled if there are concerns. Remote monitoring might also include remote needs assessment.

Care coordination is critical to ensure the needs of the individual are met seamlessly across different health settings. Implied within this is that communication between providers is efficient and effective.

Ham has described progress and challenges around NHS reform strategies aiming to achieve a greater focus on chronic disease management, which include a greater focus on supported self-management (Ham, 2009). Others have described successful implementation and dissemination of models of chronic disease self-management (Lorig et al, 2005).

People’s needs should be assessed at diagnosis and throughout treatment. This should facilitate referral to appropriate services and ensure that needs are dealt with effectively. At the end of treatment, aftercare is planned based on identified needs and predicted requirements. For some people the focus of care will be the management of acute effects and building the confidence and capacity to self manage. Other people may transit from treatment to living with cancer or beyond cancer, but with consequences of their illness or treatments. In addition to self-management skills, people in this circumstance may need more regular engagement with health-care providers—in the community or as part of a multidisciplinary specialist cancer team. Individuals triaged to this level of care may include those treated with intensive treatments, such as allogeneic bone marrow transplantation or combined modality therapies. Many survivors of childhood cancer may require this higher level of care.

Key learnings from clinical testing within the NCSI

The NCSI website includes information about all testing including information about re-designed pathways of care. In addition, Davies and Batehup (2011) describe additional examples of re-designed care, highlighting a shift towards patient empowerment.

The NCSI has identified five key phases to survivorship care:

-

Care through primary treatment from the point of diagnosis

-

Promoting rapid and as full a recovery as possible

-

Sustaining recovery

-

Management of immediate or long-term consequences of treatment

-

Management of any recurrence or disease progression.

Rehabilitation from cancer is likely to be enhanced if issues are addressed at earlier stages of the cancer pathway. Once patients have undergone initial treatment, a package of interventions to support recovery should be provided by cancer services. Effective primary care is essential for the successful support and sustained recovery of cancer survivors. Primary care providers should undertake care reviews soon after diagnosis and again when a phase of treatment has finished to permit identification of unmet needs.

In order to improve the prevention and management of the consequences of treatment, the following principles are recommended:

-

Prevent or minimise consequences where possible through improved imaging, minimally invasive surgery, targeted radiotherapy and the use of modern drugs

-

Inform patients of potential consequences when these are known and document them in treatment summaries

-

Identify groups at increased risk of late effects, including through the long-term follow-up of patients in clinical trials and better recording of treatments in national data sets

-

Where a risk is identified, adopt consistent approaches in monitoring and surveillance

-

When a new risk is identified, adopt a comprehensive approach to responding and informing patients

-

Take a proactive approach to identifying patients with established long-term effects through the use of PROMs and extracting information from health service data sets

-

Provide appropriate services for patients suffering from the consequences of treatment.

Emerging evidence from the NCSI suggests that successful transformation of aftercare pathways will:

-

Improve outcomes, reduce mortality and increase survival, while enhancing quality of life and improving patient experience;

-

Unlock resources to be reinvested in NHS cancer services; and

-

Benefit society as a whole, enabling more cancer survivors to return to work and have a more active role in their local communities.

Further implementation

NCSI has adopted several approaches to ensure spread and implementation:

(a) Education of health-care providers and purchasers about issues affecting people following initial cancer treatment as well as the discrepancy between needs and existing service provision. Service users are being empowered to ask for key components of holistic aftercare through involvement of the third sector.

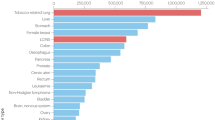

(b) Provision of data to support robust commissioning. Evidence is being collected from a number of sources; data regarding utilisation of primary health-care services following initial cancer treatment, a national cancer PROM survey, and surveys of breast, colorectal, prostate and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors 1–3 years following diagnosis. This will allow presentation of data to individual cancer centres regarding the quality of ongoing survival of their patients.

(c) Financial levers: The NHS is undergoing significant reform. The NCSI’s evidence is being utilised to provide recommendations, through Quality Standards for aftercare, for the new commissioning structure.

Next steps in England

To further develop survivorship support across England, the NCSI aims to have delivered the following achievements by 2015:

-

New services to promote faster and more comprehensive recovery

-

Fewer patients requiring routine follow-up

-

More patients supported in caring for themselves, with high-quality remote monitoring and surveillance systems in place

-

Better ambulatory care assessment and management of patients when they develop problems

-

New services for patients dealing with the consequences of treatment

-

Fewer emergency admissions, with issues being managed more effectively in the community.

Reflections from Australia

Imperatives for improved post-treatment care and barriers mentioned previously also apply in Australia. Health care in Australia shares similarities with the UK, having a universal publicly funded health-care system that is generally free to users at the point of contact, though Australia also has a parallel private health system. A significant proportion of cancer care is provided within the private system. In addition, and in contrast with England, the responsibility for health is split between federal and state and territory governments. The federal (Commonwealth) government funds state and territory governments to provide hospital-based care. Primary care is funded federally. This challenges a whole system approach to post-treatment care. Australia does not have a national cancer plan, though many state cancer plans include consideration of improved post-treatment care. Although there is very active survivorship research, work to improve survivorship care to date has been patchy and not coordinated.

Victoria, the country’s second most populous state, launched the Victorian Cancer Survivorship Program (VCSP) in late 2011. Similar to the NCSI, VCSP has a whole population focus. Initially, this program aims: to test post-treatment shared models of care across the acute and primary care settings; to evaluate these models regarding effectiveness, acceptability, sustainability and transferability to different settings; to develop resources (for consumers and service providers) to support improvements in follow-up care for people living with and beyond cancer; and to facilitate cancer survivor involvement and self-management. Six two-year pilot projects have been funded, covering different cancer types, different regional settings and age groups. Many of the principles articulated by the NCSI are reflected within the VCSP pilot projects.

Reflections from Canada

The Canadian health-care system is also publicly funded with access to care for all citizens but, in contrast to UK and Australia, there is no parallel private system. The provision of health care is a provincial responsibility. This provincial authority over health care has resulted in variations in policies and services directed at cancer survivors. Nevertheless, since 2007 Canada has had a national cancer strategy, which is implemented by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) (www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca). The CPAC has set an agenda for cancer survivorship, which has focused on pilot projects for implementing survivorship care plans (Ristovski-Slijepcevic et al, 2008). Concurrently, most provincial cancer agencies have initiatives underway to address the issue of cancer survivorship. These initiatives broadly align with the vision and system re-design articulated by NCSI, although there is variation between provinces in terms of focus and extent of re-design. The concept of risk stratification to inform care pathways, which underpins the NCSI, is highly relevant to the Canadian situation. England’s experience with risk stratification and the tools that have been developed to support it, will be very instructive as provinces further develop their approaches to survivorship care. The extent to which these various national and provincial initiatives have been implemented and their impact on survivorship care remains, at this stage, unknown.

Reflections from the United States of America

Unlike the above countries, the US does not have universal health-care coverage. Those under the age of 65, including dependent children, are covered largely under privately financed health insurance, often tied to employment status. At age 65 (and potentially earlier if they qualify as indigent or disabled) individuals become eligible for health-care benefits under the federally run Medicare program. While new and pending legislation (e.g., Affordable Care Act) aims to address some of the access to care inequities, as well as reduce fragmentation and lack of coordination in medical service delivery, the current health-care system makes instituting the kind of systematic, evidence-based programs for post-treatment care of cancer survivors adopted in the NCSI model a challenge. Despite this, interest in survivors’ health is growing rapidly in the US largely in response to growing numbers of survivors.

In the past decade, three national reports examining the unique needs and follow-up care of those postcancer treatment have been released, two by the IOM (Hewitt et al 2003, 2006) and a third by the President’s Cancer Panel (Reuben, 2004). Each of these include specific recommendations about the care of survivors, including the need for each to receive a treatment summary and survivorship care plan, along with appropriate access to guideline-informed care. Currently, all 50 states and the District of Columbia have state cancer plans; most of which include goals addressing survivorship issues. However, these are largely unfunded mandates, pursued at the discretion of and within the limits of available state funding.

The fragmented care delivery system in the US notwithstanding, efforts to foster better coordination around medical management of cancer survivors similar to that being embraced by the UK are occurring. The American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer, a hospital accrediting programme, has proposed inclusion of survivorship care planning as part of their certification process for 2015. The US is poised to advance a more uniformed approach to survivorship care and will be informed by the experience of the NCSI.

For any national survivorship program to be successful there must be push from the top (health-care delivery system and policy initiatives) and pull from the bottom (consumer desire for and use of proposed services). A particular strength of the US is the engagement and power of its consumer advocacy community. In 1986 the NCCS, a grass-roots organisation, was established which focused efforts on changing national cancer policy. The NCCS successfully advocated for the creation of the Office of Cancer Survivorship (OCS) in 1996 at the National Cancer Institute. The goal of OCS is to direct and support research that will inform the care needed to improve both the length and quality of life of all cancer survivors. Recently, OCS released a funding initiative inviting research to evaluate the efficacy and impact of survivorship care planning. Finally, Lance Armstrong’s Foundation, LIVESTRONG, created in 1997, underwrote development of LIVESTRONG centres of survivorship excellence, devoted to creating and testing models of care for long-term survivors (Campbell et al, 2011).

Other countries

This short review cannot attempt to comprehensively consider work undertaken throughout the world. It is acknowledged though that many other countries are very actively exploring new strategies to improve survivorship care, for example in the Nordic countries, The Netherlands and Germany (Hellbom et al, 2011) and in Italy (Mattioli et al, 2010).

Conclusions

Increasing numbers of cancer survivors, the broad range of issues they may experience, inadequacies of current models of care, limited health-care staffing and rising health-care costs represent significant challenges to the provision of ideal survivorship care. New models of care are urgently needed. England’s NCSI has attempted to re-design pathways of care at a whole of population level, with the goal of improving survivorship experiences, while simultaneously using limited health-care services efficiently. Established principles of aftercare are relevant internationally and are being incorporated into models of care; however, actual models must consider the local health-care setting. Sharing the lessons learned by other nations engaged in similar efforts will be an important strategy to advance survivorship care.

References

Adler NE, Page AEK (2008) Cancer Care for the Whole Patient. Meeting Psychosocial Healthcare Needs. Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting. Institute of Medicine: Washington DC

Beaver K, Luker KA (2005) Follow-up in breast cancer clinics: reassuring for patients rather than detecting recurrence. Psychooncology 14 (2): 94–101

Campbell MK, Tessaro I, Gellin M, Valle CG, Golden S, Kaye L, Ganz PA, McCabe MS, Jacobs LA, Syrjala K, Anderson B, Jones AF, Miller K (2011) Adult cancer survivorship care: experiences from the LIVESTRONG centers of excellence network. J Cancer Surviv 5: 271–282

Davies NJ, Batehup L (2011) Towards a personalised approach to aftercare: a review of cancer follow-up in the UK. J Cancer Surviv 5: 142–151

Department of Health, Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS Improvement (2010) The National Cancer Survivorship Initiative Vision. Gateway reference 12879

Frew G, Smith A, Zutshi B, Young N, Aggarwal A, Jones P, Kockelbergh R, Richards M, Maher EJ (2010) Results of a quantitative survey to explore both perceptions of the purposes of follow-up and preferences for methods of follow-up delivery among service users, primary care practitioners and specialist clinicians after cancer treatment. Clin Oncol 22: 874–884

Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, Maunsell E, Coyle D, Folkes A, Joy AA, Provencher L, Rayson D, Rheaume DE, Porter GA, Paszat LF, Pritchard KI, Robidoux A, Smith S, Sussman J, Dent S, Sisler J, Wiernikowski J, Levine MN (2011) Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29: 4755–4762

Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, Coyle D, Szechtman B, Mirsky D, Verma S, Dent S, Sawka C, Pritchard KI, Ginsburg D, Wood M, Whelan T (2006) Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physician versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol 24: 848–855

Grunfeld E, Mant D, Yudkin P, Adewuyi-Dalton R, Cole D, Stewart J, Fitzpatrick R, Vessey M (1996) Routine follow up of breast cancer in primary care: randomised trial. BMJ 313: 665–669

Ham C (2009) Chronic care in the English National Health Service: progress and challenges. Health Aff 28: 190–201

Hellbom M, Bergelt C, Bergenmar M, Gijsen B, Loge JH, Rautalahti M, Smaradottir A, Johansen C (2011) Cancer rehabilitation: a Nordic and European perspective. Acta Oncol 50: 179–186

Hewitt M, Greenfield W, Stovall E (eds) (2006) From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. The National Academies Press: Washington

Hewitt M, Weiner SL, Simone JV (eds) (2003) Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds) (2012) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, (Vintage 2009 Populations), National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/ (based on November 2011 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2012) 1975–2009

Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN (2007) Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD002200

Jefford M, Karahalios E, Pollard A, Baravelli C, Carey M, Franklin J, Aranda S, Schofield P (2008) Survivorship issues following treatment completion--results from focus groups with Australian cancer survivors and health professionals. J Cancer Surviv 2: 20–32

Lewis R, Neal RD, Williams NH, France B, Wilkinson C, Hendry M, Russell D, Russell I, Hughes DA, Stuart NS, Weller D (2009a) Nurse-led vs conventional physician-led follow-up for patients with cancer: systematic review. J Adv Nurs 65: 706–723

Lewis RA, Neal RD, Williams NH, France B, Hendry M, Russell D, Hughes DA, Russell I, Stuart NS, Weller D, Wilkinson C (2009b) Follow-up of cancer in primary care versus secondary care: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 59: e234–e247

Lorig KR, Hurwicz ML, Sobel D, Hobbs M, Ritter PL (2005) A national dissemination of an evidence-based self-management program: a process evaluation study. Patient Educ Couns 59: 69–79

Maddams J, Brewster D, Gavin A, Steward J, Elliott J, Utley M, Moller H (2009) Cancer prevalence in the United Kingdom: estimates for 2008. Br J Cancer 101: 541–547

Mattioli V, Montanaro R, Romito F (2010) The Italian response to cancer survivorship research and practice: developing an evidence base for reform. J Cancer Surviv 4: 284–289

Montgomery DA, Krupa K, Cooke TG (2007) Follow-up in breast cancer: does routine clinical examination improve outcome? A systematic review of the literature. Br J Cancer 97: 1632–1641

National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) Official website of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (Accessed 10 June 2012); available from http://www.canceradvocacy.org/about-us/

NHS Improvement—Cancer (2011) Effective follow up: Testing risk stratified pathways

NHS Improvement (2012) Stratified pathways of care... from concept to innovation. (Accessed 25 September 2012); available online at http://www.improvement.nhs.uk/documents/survivorship/Stratified_Pathways_of_Care.pdf

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Marina N, Hobbie W, Kadan-Lottick NS, Schwartz CL, Leisenring W, Robison LL (2006) Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355: 1572–1582

Reuben SH ed. (2004) President's Cancer Panel, 2003–2004 Annual Report: Living beyond cancer: Finding a new balance NIH publication no. P986 National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute

Richardson A, Addington-Hall J, Amir Z, Foster C, Stark D, Armes J, qBrearley SG, Hodges L, Hook J, Jarrett N, Stamataki Z, Scott I, Walker J, Ziegler L, Sharpe M (2011) Knowledge, ignorance and priorities for research in key areas of cancer survivorship: findings from a scoping review. Br J Cancer 105 (Suppl 1): S82–S94

Ristovski-Slijepcevic S, Nicoll I, Bennie F (2008) The Cancer Journey Action Group of the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Cancer Survivorship Workshop: Creating an Agenda for Cancer Survivorship National workshop: towards an agenda for cancer survivorship. (Accessed 10 June 2012, at http://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/wp-content/uploads/2.4.0.2.6-CPAC_CJ_Survivorship_0308_Final_E.pdf)

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2012) Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 62: 10–29

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jefford, M., Rowland, J., Grunfeld, E. et al. Implementing improved post-treatment care for cancer survivors in England, with reflections from Australia, Canada and the USA. Br J Cancer 108, 14–20 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.554

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.554

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Primary care provider–led cancer survivorship care in the first 5 years following initial cancer treatment: a scoping review of the barriers and solutions to implementation

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2024)

-

How should the healthcare system support cancer survivors? Survivors’ and health professionals’ expectations and perception on comprehensive cancer survivorship care in Korea: a qualitative study

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

Effectiveness and implementation of models of cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2023)

-

Using simulation to enhance primary care sexual health services for breast cancer survivors: a feasibility study

Supportive Care in Cancer (2023)

-

Self-Management Strategy Clustering, Quality of Life, and Health Status in Cancer Patients Considering Cancer Stages

International Journal of Behavioral Medicine (2023)