Abstract

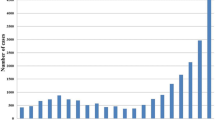

Studies examining the characteristics of patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the USA have concluded that the procedure is not being used equitably. We used population-based data from Michigan to explore disparities in the use of bariatric surgery by gender, race, and socioeconomic status. We constructed a summary measure of socioeconomic status (SES) for Michigan postal ZIP codes using data from the 2000 census and divided the population into quintiles according to SES. We then used data from the state drivers’ license list and 2004–2005 state inpatient and ambulatory surgery databases to examine population-based rates of morbid obesity and bariatric surgery in adults according to gender, race, and socioeconomic status. There is an inverse linear relationship between SES and morbid obesity. In the lowest SES quintile, 13% of females and 7% of males have a body mass index >40 compared to 4% of females and males in the highest SES quintile. Overall rates of bariatric surgery were highest for black females (29.4/10,000), followed by white (21.3/10,000), and other racial minority (8.6/10,000) females. Rates of bariatric surgery were low (<6/10,000) for males of all racial groups. An inverse linear relationship was observed between SES and rates of bariatric surgery among whites. However, for racial minorities, rates of surgery are lower in the lowest SES quintiles with the highest rates of bariatric surgery in the medium or highest SES quintiles. In contrast with prior studies, we do not find evidence of wide disparities in the use of bariatric surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sturm R. Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000–2005. J R Inst Public Health. 2007;121:492–6.

Santry H, Gillen D, Lauderdale D. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(15):1909–17.

Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom C. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):741–52.

Dymek MP, Le Grange D, Neven K, et al. Quality of life after gastric bypass surgery: a cross-sectional study. Obes Res. 2002;10(11):1135–42.

Hafner RJ, Watts JM, Rogers J. Quality of life after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Int J Obes. 1991;15(8):555–60.

Adams T, Gress R, Smith S, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):753–61.

Mokdad A, Bowman B, Ford E, et al. The continuing epidemic of obesity and diabetes in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286(10):1195–200.

Flegal K, Carroll M, Ogden C, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;288(14):1723–7.

Livingston E, Ko C. Socioeconomic characteristics of the population eligible for obesity surgery. Surgery. 2004;2004(135):3.

Levi J, Vinter S, Richardson L, et al. F as in Fat: how obesity policies are failing in America. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health; 2009.

Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):99–106.

Black D, Taylor A, Coster D. Accuracy of self-reported body weight: stepped Approach Model component assessment. Health Educ Res. 1998;13:301–7.

Engstrom J, Paterson S, Doherty A, et al. Accuracy of self-reported height and weight in women: an integrative review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2003;48:338–45.

Ezzati M, Martin H, Skjold S, et al. Trends in national and state-level obesity in the USA after correction for self-report bias: analysis of health surveys. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:250–7.

Jeffery R. Bias in reported body weight as a function of education, occupation, health, and weight concern. Addict Behav. 1996;21:217–22.

Villanueva E. The validity of self-reported weight in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2001;1:11.

Zhang J, Feldblum P, Fortney J. The validity of self-reported height and weight in perimenopausal women. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1052–3.

Cawley J, Burkhauser R. Beyond BMI: the value of more accurate measures of fatness and obesity in social science research. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

Deyo R, Cherkin D, Ciol M. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9.

Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata J. 2004;4(3):227–41.

Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: update. Stata J. 2005;5(2):188–201.

Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: update of ice. Stata J. 2005;5(4):527–36.

Bach P, Cramer L, Warren J, et al. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(16):1198–205.

Skinner J, Weinstein J, Sporer S, et al. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in rates of knee arthroplasty among Medicare patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1350–9.

Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2002.

Martin M, Beekley A, Kjorstad R, Sebesta J. PL-217. Socioeconomic disparities in eligibility and access to bariatric surgery: A national population-based analysis. In: 26th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS). Dallas, TX; 2009.

Sobal J, Stunkard A. Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:260–75.

Wang Y, Beydoun M. The obesity epidemic in the United States—gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28.

Zagorsky J. Health and wealth: the late-20th century obesity epidemic in the U.S. Econ Hum Biol. 2005;3:296–313.

Zhang Q. Socioeconomic inequality of obesity in the United States: do gender, age, and ethnicity matter? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1171–80.

Zhang Q, Wang Y. Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. adults: 1971 to 2000. Obes Res. 2004;12:1622–32.

Cooper G, Yuan Z, Landefeld C, et al. Surgery for colorectal cancer: race-related differences in rates and survival among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(4):582–6.

Dominitz J, Maynard C, Billingsley K, et al. Race, treatment, and survival of veterans with cancer of the distal esophagus and gastric cardia. Med Care. 2002;40(1 Supplement):I-14–26.

Miller K, Gleaves D, Hirsch T, et al. Comparisons of body image dimensions by race/ethnicity and gender in a university population. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27(3):310–6.

Allison D, Hoy M, Fournier A, et al. Can ethnic differences in men's preferences for women's body shapes contribute to ethnic differences in female adiposity? Obes Res. 1994;1(6):425–32.

Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–10.

Subramanian S, Chen J, Rehkopf D, et al. Comparing individual- and area-based socioeconomic disparities: a multilevel analysis of Massachusetts births, 1989–1991. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(9):823–34.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Birkmeyer, N.J.O., Gu, N. Race, Socioeconomic Status, and the Use of Bariatric Surgery in Michigan. OBES SURG 22, 259–265 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0210-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0210-3