Abstract

BACKGROUND

Psychosocial factors, including social support, affect outcomes of cardiovascular disease, but can be difficult to measure. Whether these factors have different effects on mortality post-acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in men and women is not clear.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the association between living alone, a proxy for social support, and mortality postdischarge AMI and to explore whether this association is modified by patient sex.

DESIGN

Historical cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS/SETTING

All patients discharged with a primary diagnosis of AMI in a major urban center during the 1998–1999 fiscal year.

MEASUREMENTS

Patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were obtained by standardized chart review and linked to vital statistics data through December 2001.

RESULTS

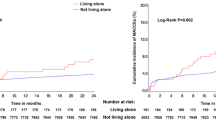

Of 880 patients, 164 (18.6%) were living alone at admission and they were significantly more likely to be older and female than those living with others. Living alone was independently associated with mortality [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 1.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.0–2.5], but interacted with patient sex. Men living alone had the highest mortality risk (adjusted HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.1–3.7), followed by women living alone (adjusted HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.7–2.2), men living with others (reference, HR 1.0), and women living with others (adjusted HR 0.9, 95% CI 0.5–1.5).

CONCLUSIONS

Living alone, an easily measured psychosocial factor, is associated with significantly increased longer-term mortality for men following AMI. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm the usefulness of living alone as a prognostic factor and to identify the potentially modifiable mechanisms underlying this increased risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, et al. “Stress” and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors, National Heart Foundation of Australia position statement update. Med J Aust. 2003;178:272–6.

Strike PC, Steptoe A. Psychosocial factors in the development of coronary artery disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;46:337–47.

Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, et al. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: the emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:637–51.

Albus C, Jordan J, Herrmann-Lingen C. Screening for psychosocial risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease: recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:75–9.

Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, Horwitz RI. Emotional support and survival after myocardial infarction: a prospective, population-based study of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1003–9.

Case RB, Moss AJ, Case N, McDermott M, Eberly S. Living alone after myocardial infarction: impact on prognosis. JAMA. 1992;267:515–9.

Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Gender, depression, and one-year prognosis after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:26–37.

Kristofferzon M-L, Löfmark R, Carlsson M. Perceived coping, social support, and quality of life 1 month after myocardial infarction: a comparison between Swedish women and men. Heart Lung. 2005;34:39–50.

Lauzon C, Beck CA, Huynh T, et al. Depression and prognosis following hospital admission because of acute myocardial infarction. Can Med Assoc J. 2003;168:547–52.

Ziegelstein RC. Depression after myocardial infarction. Cardiol Rev. 2001;9:45–51.

Bello N, Mosca L. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease in women. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;46:287–95.

van Jaarsveld CHM, Ranchor AV, Kempen GIJM, et al. Gender-specific risk factors for mortality associated with incident coronary heart disease—a prospective community-based study. Prev Med. 2006;43:361–7.

Jelinski SE, Ghali WA, Parsons GA, Maxwell CJ. Absence of sex differences in pharmacotherapy for acute myocardial infaction. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20:899–905.

International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modifications, 5th ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Medicode Publications Inc; 1996.

Levy AR, Tamblyn RM, Fitchett D, McLeod PJ, Hanley JA. Coding accuracy of hospital discharge data for elderly survivors of myocardial infarction. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:1277–82.

Chang I-M, Gelman R, Pagano M. Corrected group prognostic curves and summary statistics. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35:669–74.

Ghali WA, Quan H, Brant R, et al. Comparison of 2 methods for calculating adjusted survival curves from proportional hazards models. JAMA. 2001;286:1494–7.

Li C, Engström G, Hedblad B, Janzon L. Sex-specific cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in a cohort treated for hypertension. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1523–9.

Prescott E, Godtfredsen N, Vestbo J, Osler M. Social position and mortality from respiratory diseases in males and females. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:821–6.

Davis MA, Neuhaus JM, Moritz DJ, Segal MR. Living arrangements and survival among middle-aged and older adults in the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:401–6.

Murata C, Takaaki K, Hori Y, et al. Effects of social relationships on mortality among the elderly in a Japanese rural area: an 88-month follow-up study. J Epidemiol. 2005;15:78–84.

Glass TR, De Geest S, Weber R, et al. Correlates of self-reported nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients: the Swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:385–92.

O’Shea JC, Wilcox RG, Skene AM, et al. Comparison of outcomes of patients with myocardial infarction when living alone versus those not living alone. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1374–7.

Kaplan JR, Manuck SB. Status, stress, and atherosclerosis: the role of environment and individual behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:145–61.

Lundberg, U. Stress hormones in health and illness: the roles of work and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1017–21.

Kristofferzon M-L, Löfmark R, Carlsson M. Myocardial infarction: gender differences in coping and social support. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:360–74.

Jackson L, Leclerc J, Erskine Y, Linden W. Getting the most out of cardiac rehabilitation: a review of referral and adherence predictors. Heart. 2005;91:10–4.

Joynt KE, O’Connor CM. Lessons from SADHART, ENRICHD, and other trials. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:S63–6.

Johansen H, Nair C, Mao L, Wolfson M. Revascularization and heart attack outcomes. Health Rep. 2002;13:35–46.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the Calgary Health Region and Institute of Health Economics. The funding organizations did not play a role in any of the following: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. David Hogan for his mentorship and helpful suggestions regarding the manuscript. This study is part of a collaborative network (involving Drs. Schmaltz, Ghali, Maxwell & King) with the gender and sex determinants of circulatory and respiratory diseases: interdisciplinary enhancement teams grant program, Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Gender and Health and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr. Maxwell is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Institute of Aging) and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR). Dr. Ghali and Dr. King also receive salary support from AHFMR. Dr. Ghali is also funded by a Canada Research Chair in Health Services Research. Dr. Maxwell had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmaltz, H.N., Southern, D., Ghali, W.A. et al. Living Alone, Patient Sex and Mortality After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 572–578 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0106-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0106-7