Abstract

Men who have sex with men experience high rates of psychosocial health problems such as depression, substance use, and victimization that may be in part the result of adverse life experiences related to cultural marginalization and homophobia. These psychosocial health conditions interact to form a syndemic which may be driving HIV risk within this population. However, MSM also evidence great resilience to both the effects of adversity and the effects of syndemics. Investigating and harnessing these natural strengths and resiliencies may enhance HIV prevention and intervention programs thereby providing the additional effectiveness needed to reverse the trends in HIV infection among MSM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Syndemic Theory and the Theory of Syndemic Production

Homophobia is a pervasive cultural phenomenon that impacts all members of society. Institutionalized forms of homophobia such as marriage, adoption, and tax laws that favor heterosexual couples, or “glass ceiling” style inequalities in the workplace, help to reinforce the belief that sexual minorities are less deserving of rights and protections than heterosexuals. Overt forms of homophobia such as hate crimes, anti-gay rhetoric and public demonstrations in opposition to gay rights reinforce these messages of inequality and create a hostile environment in which sexual minorities must exist. The marginalizing effects of homophobia and heterosexism are consistent with Meyer’s Minority Stress Theory as applied to sexual minorities. This theory suggests that experiences of social discrimination based on sexual orientation work to reduce the overall health profile of sexual minority individuals [1]. This process happens over time as minority individuals are exposed to both explicit and implicit discrimination and social marginalization. These experiences cause stress to the individual, thereby lowering self-esteem and increasing emotional distress and a sense of social isolation, all of which render the individual more vulnerable to serious psychosocial health problems.

Among gay and bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men (MSM), evidence suggests that minority stress increases their risk for multiple health issues, including depression, anxiety, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors [2]. While a fully matured adult gay man may be able to withstand these stressors, sexual identity development, or at least a sense of “differentness” often occurs long before adulthood, when young men do not necessarily have the skills and resources to cope with such adversity. It has been well demonstrated that experiences of adversity during adolescence in the general population are associated with the development of psychosocial health problems such as substance use, depression and anxiety, victimization and participation in high risk sexual behaviors in later life [3, 4]. It is therefore not surprising that gay men and other MSM face marked disparities in levels of these psychosocial health outcomes compared to their heterosexual peers [5–7].

It has further been shown that these psychosocial health problems have a tendency to co-occur in vulnerable MSM populations [8–11]. While each of these problems independently has a negative impact on the overall health and quality of life of the individual, an increasing body of evidence suggests that when these problems co-occur, they interact in a way that amplifies the effects of each other. This interaction is referred to as a syndemic (defined by the CDC as “two or more afflictions, interacting synergistically, contributing to excess burden of disease in a population” [12]). Moreover, there is evidence that syndemics among gay men not only intensify psychosocial health outcomes, but may also be driving the HIV epidemic [13] as well as contribute to other health disparities among gay men.

A number of studies provide support for a Syndemic Theory in gay men. Analyzing data from the Urban Men’s Health Study, a probability sample of MSM in 4 major US cities, Stall et al. found that partner violence, substance abuse, childhood sexual abuse, and depression were all positively associated with each other. A further analysis of this data showed that the greater the number of psychosocial health problems, the stronger the association with high-risk sexual behaviors and HIV infection [13]. Similarly, Mustanski et al. found that among a sample of young MSM, endorsement of each additional psychosocial health problem significantly increased the odds of unprotected anal intercourse, multiple sex partners, and HIV seroprevalence [14]. These syndemic analyses have recently been replicated, for the first time, in a non-US based sample of MSM. Investigators in Bangkok, Thailand found that increasing numbers of psychosocial health conditions were positively and significantly associated with increasing rates of both unprotected anal intercourse and HIV prevalence [15].

Corollaries of Syndemic Theory

Syndemic Processes Begin During Youth

Given that homophobia is a culture-wide phenomenon, it follows that children are exposed to homophobic messages and actions, and therefore that syndemic processes among MSM likely begin at a young age. As mentioned previously, sexual identity formation tends to start during or near adolescence. Without access to social support and acceptance during this period, young men may internalize negative attitudes towards sexual minorities, and eventually develop mental and behavioral health problems. This has been demonstrated through a series of meta-analyses comparing rates of psychosocial health outcomes between heterosexual and sexual minority youth. In brief, these studies showed that sexual minority youth are significantly more likely to experience depression (in preparation), victimization [16], substance use [17] and sex under the influence of drugs and alcohol [18] compared to their heterosexual peers.

Addressing Multiple Epidemics may Raise HIV Prevention Effectiveness

Besides giving us a framework for understanding the high rates of psychosocial outcomes and HIV among MSM, Syndemic Theory also provides insight into ways to raise HIV prevention effectiveness. According to Syndemic Theory, raising levels of health across any or all psychosocial health conditions will have a positive impact on levels of HIV risk and HIV prevalence as well as the other component epidemics that together constitute the set of syndemic conditions. If syndemic conditions work together to increase vulnerability to HIV, then mitigation of one or more of these conditions should work to decrease HIV vulnerability. Therefore, interventions for MSM that successfully address psychosocial health conditions will likely improve HIV prevention behaviors even if there is not a direct focus on HIV prevention.

Despite Syndemic Processes, Most Gay Men are Resilient

Finally, although it is necessary to acknowledge and study syndemic processes, it is just as important to recognize that not all sexual minorities who have experienced adversity go on to develop syndemic conditions, and not all of those who develop syndemic conditions become HIV infected. In fact, the original investigation of syndemic production among gay men found that, of the men who experienced three or more psychosocial health problems, 23% had recently engaged in high risk sex and 22% were HIV positive [19]. These numbers are certainly alarming, but perhaps the most important story here is that 77% of these men had avoided engaging in high risk sexual behaviors and 78% had remained HIV negative despite the fact that they were dealing with a myriad of psychosocial health problems. For these individuals to be able to withstand persistent cultural marginalization and avoid the natural sequelae of those experiences indicates remarkable resilience and strength within this population. Resilience as a sub-cultural phenomenon is an area of study that has yet to receive much focus, but that appears to have great potential as an approach for the health promotion of gay men.

Deficit Assumptions Underlying HIV Intervention Design for Gay Men

Currently the design of HIV behavioral prevention interventions is informed by the lessons learned from the relatively small percentage of gay men who have fallen victim to syndemic processes. The approach leads to an attempt to rectify the perceived “wrongs” evidenced by this small group of men. The underlying assumption of this approach is that these gay men are flawed or are deficit of the skills and/or abilities needed to prevent HIV. Below are examples of frequently employed intervention aims and the deficit assumptions upon which they are based:

-

Raise condom use skills (gay men don’t know how to use condoms)

-

Raise condom negotiation skills (gay men don’t know how to negotiate sex)

-

Change peer norms (gay men have unhealthy peer norms, especially around sex)

-

Raise skills to face homophobia (gay men have few skills to face homophobia)

A set of meta-analyses showed that current HIV behavioral prevention interventions for gay men reduce HIV risk taking by approximately one third [20, 21]. While a reduction in risk behaviors of this magnitude is admirable, much greater impact is needed to alter the current trends in infection rates among gay men. Because existing interventions are focused on deficits, gay men may perceive the negative focus as judgmental and they may therefore be less likely to accept, adhere to, and complete the intervention. Interventions that focus on strength and resilience rather than deficits could improve both intervention acceptability and efficacy.

Resilience is Common Among Gay Men

Evidence for strengths and resilience among gay men is widespread in both scientific literature and historical accounts of gay culture. For instance, in an investigation of tobacco use among gay men, Greenwood et al. found that a greater proportion of gay men reported cessation of tobacco use than reported current daily tobacco use (26.9 vs. 25.7%) indicating a voluntary inclination towards health promotion and recovery [22]. Most gay men have also managed to avoid problematic drug use despite widespread use of recreational drugs generally perceived to be addictive [6, 23]. Most notable, however, is that over the past 40 or so years, gay men have been part of one of the most impressive and effective bids for civil rights in history, all while facing community-wide devastation from the HIV epidemic. This suggests that taking advantage of naturally occurring strengths could improve prevention efforts by capitalizing on the skills, resources, and strengths that already exist among gay men and within gay male communities.

Strengths and Health Promotion

A move toward strength-based health promotion interventions does not necessitate that we ignore deficits in knowledge or skills that contribute to risky behaviors. Rather, a strength-based approach can address these deficits by relying on strengths. Table 1 Below lists a few examples of correlates of HIV risk behaviors that can be addressed by focusing interventions or intervention activities on strengths.

Strength-based approaches to health promotion can be utilized not just in HIV prevention programs, but also in addressing the psychosocial health conditions (syndemic conditions) that increase susceptibility to HIV.

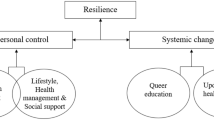

Towards the Development of a Theory of Resilience Among Gay Men

Strength-based approaches to HIV prevention will be aided greatly by the development of a Theory of Resilience that is specifically tailored to MSM. This can be accomplished through further investigation of naturally occurring strengths and resiliencies that exist within both individuals and communities. For instance, investigations into substance-using MSM often focus on the correlates of problematic substance use behaviors; however, studies that focus on the correlates of abstinence, non-problematic use, or spontaneous remission from use may be more informative for prevention and intervention programs. Similarly, studying how men with multiple syndemic conditions remain sexually safe and HIV negative over time or how community mobilization can strengthen community interactions and supports will likely improve health promotion efforts among gay men.

Without sufficient information about what strengths exist among MSM, and how these strengths contribute to resilience, it is difficult to envision an empirically supported Theory of Resilience. However, it is possible to imagine how family supports and school programs such as Gay/Straight Alliances could help young MSM fend off the negative effects of bullying or institutionalized homophobia. Having these supports for young MSM (or gay adolescents) would likely attenuate the association between early life adversity and syndemic production. Further, if that same individual were exposed to healthy coping strategies and community supports as an adult, he may also develop a sense of shamelessness that could be protective against the effects of overt homophobia and marginalization. This sense of shamelessness or pride may be one of the greatest strengths that sexual minority communities have developed and it may be very important in disrupting the progression of syndemic development and its impact on HIV risk and infections.

Sexual minority individuals and communities have evidenced considerable strengths over the past 30 years, and they have done this in the face of extreme homophobia and marginalization. Even more impressive is the fact that the momentum of the initial, post-Stonewall Gay Rights Movement was not derailed or diminished by the AIDS epidemic that soon followed. In fact, our communities have used this adversity as a motivating force to stand up and demand equal rights in all facets of life from health care to marriage. This strength and resilience has helped our communities overcome considerable challenges and still thrive in the face of adversity. A Theory of Resilience among gay men can provide a template to harness this strength and so increase the impact of health promotion efforts among gay men.

References

Diaz RM. Latino gay men and HIV : culture, sexuality, and risk behavior. New York: Routledge; 1998.

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97.

Weich S, Patterson J, Shaw R, Stewart-Brown S. Family relationships in childhood and common psychiatric disorders in later life: systematic review of prospective studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(5):392–8.

Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S163–75.

Stall R, Wiley J. A comparison of alcohol and drug use patterns of homosexual and heterosexual men: the San Francisco men’s health study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1988;22(1–2):63–73.

Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, et al. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. [erratum appears in Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):776]. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):278–85.

Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri RO. Unequal opportunity: health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Greenwood GL, Relf MV, Huang B, Pollack LM, Canchola JA, Catania JA. Battering victimization among a probability-based sample of men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1964–9.

Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, Stall R. Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: the urban men’s health study. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(4):557–84.

Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):725–30.

Cruz JM, Peralta RL. Family violence and substance use: the perceived effects of substance use within gay male relationships. Violence Vict. 2001;16(2):161–72.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syndemics Prevention Network. Spotlight on syndemics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/syndemics/. Accessed July 2010.

Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–42.

Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):37–45.

McCarthy K, Wimonsate W, Guadamuz T, et al. Syndemic analysis of co-occurring psychosocial health conditions and HIV infection in a cohort of men who have sex with men (MSM) in Bangkok, Thailand. Vienna: International AIDS Conference; 2010.

Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A meta-analysis to examine disparities in childhood physical and sexual abuse among sexual and non-sexual minorities. Am J Public Health. 2010 (in press).

Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103(4):546–56.

Herrick A, Marshal MP, Smith HA, Sucato G, Stall R. Sex while intoxicated: a meta-analysis comparing heterosexual and sexual minority youth. J Adolesc Health. 2010 (in press).

Stall R, Friedman M, Catania J. Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: a theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri RO, editors. Unequal opportunity: health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 251.

Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, et al. A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(2):228–41.

Johnson WD, Hedges LV, Diaz RM. Interventions to modify sexual risk behaviors for preventing HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003(1):CD001230.

Greenwood GL, Paul JP, Pollack LM, et al. Tobacco use and cessation among a household-based sample of US urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(1):145–51.

Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the urban men’s health study. Addiction. 2001;96(11):1589–601.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gerra L. Bosco for her invaluable feedback on this article and for her editorial assistance. We would also like to thank all of the participants in the studies cited for their contribution to the understanding and improvement of gay men’s health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herrick, A.L., Lim, S.H., Wei, C. et al. Resilience as an Untapped Resource in Behavioral Intervention Design for Gay Men. AIDS Behav 15 (Suppl 1), 25–29 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-9895-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-9895-0